The human condition

By William Wetherall

[Forthcoming]

Community

[Forthcoming]

Crime and delinquency

[Forthcoming]

Crime statistics

NPA statistics

Police in Japan deserve a lot of praise for a job generally well done. Standards vary from locality to locality, yet on the whole, community policing in Japan, and criminal investigation, rank among the finest in the world.

In some ways, though, the police are not as competent as they could be.

One major area of police work that needs improvement is the manner of compiling and reporting crime statistics.

If five more people were murdered this year than last year, would this mean that crime is increasing?

In terms of case load, yes.

If you've got to investigate five more homicides, then you're going to work more.

There will be more 110 calls, more investigations, more forensic autopsies, more canvassing of neighborhoods around crime scenes, more car chases, more and apprehensions of culprits. There will be more charges, more prosecutions, more court trials, more convictions, more prisoners, more executions, and more ex-convicts. And more victims. Let's not forget them.

And alas, there will be a lot more paperwork along the full stretch of the convoluted law-enforcement highway. More reports to write, present, and file.

But this does not mean that criminality is increasing, or that the streets are more dangerous.

What if the population of potential criminals were growing faster than the number of cases? Then the chances of anyone committing a crime would be less. If the population of potential victims were also rising faster, then the odds of becoming a victim would also be less.

Police crime reports, however, seldom go into the demographic factors that affect either criminality (the likelihood that a crime will be committed) or danger (the possibility that one will be a victim of a crime). They dwell on the number of crimes, not the probability of committing or becoming a victim of one.

The mass media are in the habit of simply regurgitating the official statistics. News writers are rarely motivated to figure out what the numbers really mean. And conservative editors and other opinionists usually assume that an "increase" in crime is a "warning" that society is going to the dogs.

If the politicians, the bureaucrats, and the public believe that society is becoming more dangerous, then the police can request, and receive, more funds to spend on more personnel and facilities for dealing with the presumably greater crime "problem" and its causes.

Government agencies naturally use larger work loads to justify bigger budgets, and such requests are not necessarily out of line. Yet leaving the meanings of the greater crime figures ambiguous, and encouraging the impression that society is more dangerous, bring the police something more important than operating funds.

The more dangerous a society is perceived to be, the more important are deemed its police and their mission to maintain public order and safety. And perhaps police everywhere thrive on the prestige that attaches to being "the nurses of the people"--to borrow the title of Karel van Wolferen's insightful chapter on the police in The Enigma of Japanese Power (1992).

While some police officers have invented or staged crimes to get attention or meet an arrest quota, and others have been guilty of entrapment, law enforcement bureaucrats in Japan are not in the habit of provoking more crime for the sake justifying stronger police forces -- in the way that some defense bureaucrats and military commanders and in the United States have exploited war opportunities in order to develop and test new weapons, and even season soldiers. Still, the police are professionally challenged by increasing case loads. And they both covet, and relish in, the glory that comes when their efforts to combat and prevent crime "result" in fewer cases.

The praise for doing a job well done would not be as sweet were it clear that a "decrease" in crime had little or nothing to do with police work, but everything to do with changes in the age, sex, and ethnic composition of the general population--and with the ways in which crime statistics are compiled and reported.

Prostitution

[Forthcoming]

Gangsters

[Forthcoming]

Medical examination

[Forthcoming]

Jurisdiction

Most communities do not especially welcome military bases for a variety of reasons, all the more so if the bases are those of foreign countries. Communities usually have little or no say in whether a base is located in their back yard, however, as military affairs are generally the province of the state or the victor.

Airbases and infantry and armor firing ranges create concern about noise and safety, and hospitals that receive wounded soldiers from war zones cause the residents of surrounding neighborhoods to worry about infectious diseases and body disposal. But all bases engender apprehensions about the build-up around the bases of bars, cabarets, hotels, and other businesses that cater to the soldiers, and effects of their off-base activities on children who witnesses fraternization between soldiers and women. And they create anxiety about violent crimes by soldiers against local people.

Crimes committed by foreign military personnel create the additional problem of which state has jurisdiction. U.S. military bases in Japan, like the American embassy and its consulates, are essentially extensions of U.S. territory in Japan, and as such they enjoy some extraterritorial privileges, in addition to diplomatic immunity.

Today, a crime committed by a soldier while on duty against another soldier, whether on or off base, is generally tried by a U.S. military court. If committed against a Japanese when off duty, whether on or off base, the crime is usually tried by a Japanese court. But the determination of court venue in cases between these two extremes is not always easy.

During the Allied Occupation of Japan, Japan's sovereignty was in the hand of the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP). No one in Japan at the time was entirely exempt from Japanese laws, but some were more subject to the reach of Japanese jurisdiction than others.

Most United Nations nationals -- meaning nationals of the Allied Powers or "1st nationals" -- were under SCAP's jurisdiction and were generally tried in Allied military courts. Japanese courts were the most like venue for trials of people SCAP classified as Japanese, Germans, or other former enemy nationals ("2nd nationals"), and of Chosenese (Koreans) and Taiwanese (Formosans), who were Japanese but classified by SCAP as "non-Japanese" for repatriation and alien registration purposes ("3rd nationals").

After the Occupation of Japan ended in 1952, Allied law and courts also ended, and all aliens in Japan, included nationals of the Allied nations, became subject to Japanese law enforcement. However, diplomats were partly immune under international conventions regarding diplomatic relations. And under status-of-forces agreements, U.S. and U.N. military personnel in Japan were subject to military rather than Japanese laws and courts in most incidents that occurred on a military facility or when on duty outside a facility.

In principle, Japan had unquestioned jurisdiction in all off-base, off-duty incidents involving foreign military personnel. But Japan sometimes claimed jurisdiction in on-duty incidents including some that took place on a military facility. Attempts by U.S. or other foreign military forces to try these cases in their own courts infuriated Japanese critics of extraterritoriality in Japan.

Today, under somewhat revised Status of Forces (SOFA) rules, U.S. military authorities are much more cooperative. But there is still a public perception that the United States is reluctant to let Japanese courts try its military personnel, and an impression that U.S. military courts are too lenient in cases of rape and murder involving Japanese nationals.

In fact, the opposite appears to be true. U.S. Forces personnel have generally received lighter sentences in Japanese courts, not because they are accorded special treatment, but because Japan's penal codes and practices appear to be more lenient in comparison with military and civilian standards of justice in the United States.

Death and thanatology

By William Wetherall

An awareness of death is supposed to distinguish us from most other animals, and the attention we give to the disposal of our dead is widely considered uniquely human. To the extent that the discovery of death requires a conscious imputation of meaning to death, an awareness of death implies the capacity for religious thought in particular and, more generally, for what anthropologists have called culture.

Thanatology is not, however, merely a study of the culture of death or eschatology. It is rather a study of life through the window of our experience of mortality in all forms of life. It is, after all, the living and not the dead who, like it or not, face the inevitability of death, and who become increasingly aware with age that their biological clock is ticking, that life itself is a progressive disease which could prove fatal at any time, if not from illness or old age then in an accident or natural disaster, or at the hand of another if not oneself. It is also the living who must ceremoniously or otherwise dispose of the bodies of those who die, kin or stranger, friend or foe.

The most common word for "thanatology" in Japanese is shiseikan, literally "death-life-view" or "views of life and death". However, the Chinese characters for "shi" (death) and "sei" (life) are compounded as both shisei (death-life) and seishi (life-death).

Some Buddhist texts use the term "seishi" to refer to the events of birth and death in a life cycle that which are not necessarily the phenomena of life and death). A Taiwanese suicide preventionist preferred seishikan because it expressed the fact that life precedes death, though one could just as well argue that shiseikan expresses the hope that life and survive death. Kamo no Chomei may have had this in mind when observing in his 14th-century classic Hojoki that "No one knows whence we come when born or where we go when we die."

The term seishi (alternatively shoshi) means "living and dying", hence the expression shoshi fumei meaning "not known whether alive or dead".

Mortality

People born in Japan have the highest or nearly highest longevity in the world. Most boys and girls born today can expect to live well into their 80s and even 90s -- about twice as long as in the mid 19th century, and two decades longer than in the mid 20th century.

Crude annual mortality (M) is the number of people who die (D) during a year per 100,000 living population (P). That is, M = 100,000 * D / P.

Crude and age-adjusted morality rates for Japan, 1900-2003

Mortality rates Life

Crude Age-adjusted expectancy

Year Population Deaths Total Males Females Males Females

______________________________________________________________________

1900 43,847,000 910,744 2,077.1 42.8 44.3

1910 49,184,000 1,064,234 2,163.8 (1891-1898)

1920 55,963,053 1,422,096 2,541.1

1930 64,450,005 1,170,867 1,816.7

1940 71,933,000 1,186,595 1,649.6

1950 83,199,637 904,876 1,087.6 50.06 62.97

1960 93,418,501 706,599 756.4 1,476.1 1,042.3

1970 103,119,447 712,962 691.4 1,234.6 823.3 69.84 75.23

1980 116,320,358 722,801 621.4 923.5 579.8 73.57 79.00

______________________________________________________________________

1985 120,287,484 752,283 625.5 812.9 482.9 74.95 80.75

______________________________________________________________________

1990 122,721,397 820,305 668.4 747.9 423.0 75.92 81.90

2000 125,387,000 961,653 765.6 634.2 323.9 77.72 84.60

2003 126,139,000 1,014,951 804.6 601.6 302.5 78.36 85.33

______________________________________________________________________

From various Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare sources

Crude mortality was over 2000 at the beginning of the 20th century and remained fairly constant until about 1925, when it began to fall below 2000. It continued to fall and was about 1500 at the end of World War II in 1045. From the late 1940s it began to very rapidly fall to 1000 by 1950 and 700 by 1965. It reached 600 by 1980, when it began to climb again to over 800 by the early 2003.

Throughout this period, longevity has been rising. Even after crude mortality began to climb again in the late 20th century, longevity continued to rise. So what gives?

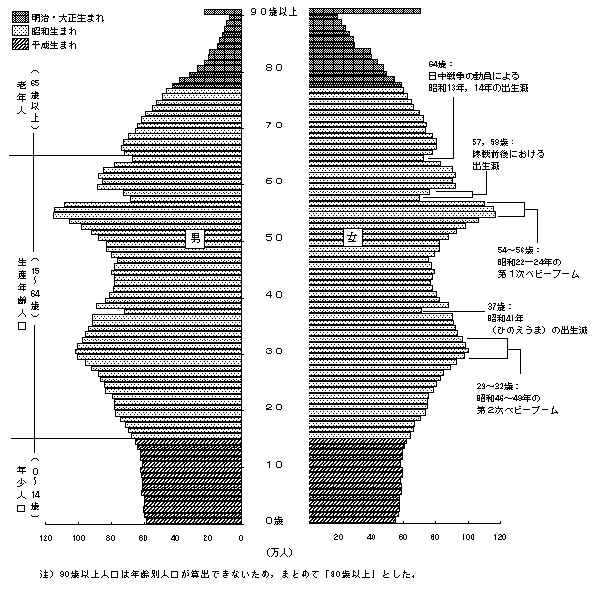

Skewed population pyramid

Annual mortality is a static ratio of dead to living during a given period. It does not accurately reflect demographic dynamics.

Age-adjusted annual mortality rates attempt to eliminate or minimize effects of skewing due to changes in the age composition of the population and the male/female ratio or gender balance. The age-adjusted rates in the above table show that the risk of dying in a given year has been, and continues to, drop for both sexes.

100 percent

The true mortality for both sexes, in all countries, throughout time, is 100 percent. All people die. The question is how long the average person lives -- and that has been increasing.

Death and mourning

How people are reported to die reflects attitudes toward both death and personality. Not everyone who dies gets public attention, and not everyone who gets public attention is mourned in death or later memorialized.

A popular public personality will of course be mourned and to some extent remembered by his or her generation. Some public figures become memorialized by several generations.

The social meanings imputed to a person's station in life is probably the most important factor in determining who gets publicity while on their death bed, is publicly mourned when they die, and is memorialized in the future.

There was nothing remarkable about Emperor Meiji's death, nothing even very remarkable about his life as a human being -- except that he had been the reigning emperor of Japan for nearly half a century. Not just any half century, either -- but the half century during which Japan was transformed -- from an isolationist confederation of local domains forced to grant foreign powers extraterritorial privileges -- to an independent state with world-class laws, schools, and industries, and military might.

Meiji's son Emperor Taishō made little impression on the nation in life or in death. The life and death of Taishō's son, Emperor Shōwa, otherwise known as Hirohito, moved the nation and the world -- partly because he was the monarch of Japan during the rise of militarism that culminated in the Pacific War -- and partly because, after the war, he remained the emperor for 43 years. He is likely to be remembered even more than his grandfather, simply because of when he was who he was.

The circumstances of a death, including it's setting, occasion, and cause, may get someone more attention than they would otherwise have gotten. Had Mishima Yukio simply died in an automobile accident or of a heart attack, there would not have been so much reportage and, even today, so much looking back on the occasion and manner of his death.

Cremation and burial

Body counts are most useful for people in the death industry. Crude mortality rates express how many priests, morticians, and grave diggers are needed per 100,000 population in order to meet the needs of the survivors of those who die.

Bodies in homes and hospitals, on roads and in woods, need disposal. Burial was the usual method of disposal until the introduction of cremation with Buddhism from the continent through Korea. However, cremation did not become the predominant method of disposal until fairly recently. Burial practices, which varied regionally, continued until all but prevented by present-day laws.

Still there rural pockets where some people prefer to bury their dead in family graveyards. Ibaraki prefecture has had a conspicuously higher burial rate in recent decades.

Afterlife

The biggest sector of the death industry attends to the spiritual needs of the living to ensure that the souls of their deceased ancestors rest in peace. Buddhist temples, and the priests who manage them, depend on the living to pay for their facilities and services -- graveyards and sometimes columbariums on the temple grounds, and funeral and memorial rites.

Family and generation

[Forthcoming]

Children and teens

[Forthcoming]

Elderly

[Forthcoming]

Marriage

[Forthcoming]

Women

[Forthcoming]

Law

[Forthcoming]

Media and popular culture

[Forthcoming]

Magazines

[Forthcoming]

Privacy

[Forthcoming]

Poverty and underclass

[Forthcoming]

Poverty

[Forthcoming]

Homeless

[Forthcoming]

Welfare

[Forthcoming]

Psychology

[Forthcoming]

Sexology

Koshinaga Jushiro observed that sex is pleasurable in order to induce a couple to mate. Why else would anyone go to so much trouble? But the former Tokyo Chief Medical Examiner went on to point out that sex is not therefore something we are meant to pursue for pleasure.

To be sure, ends and means are easily confused in a society that lacks a moral grip on sex, the most fundamental imperative of our biological condition.

No wonder the increase in sexually related crime--or at least an increase in the reporting of criminalized sexual behavior.

The late Hiroshi Wagatsuma was a student of marital conflict, broken families, and other social pathologies that are likely to involve ruptures of sexual bonds between couples. Returning to Japan after a long sojourn in American academia, where he wrote mainly about minorities in Japan, Wagatsuma turned his attention to sex, which he called "the last frontier of anthropology." And he began reporting his observations of changing sexual mores in Southern California suburbs.

While there is a danger of reducing all human activity to sexual impulses, the fact remains that a species survives not only because its members are able to mate, but because they are also able to discharge the longer term, less orgasmic social duties that follow carnal reproduction.

Sexual behavior

[Forthcoming]

Sex industry

[Forthcoming]

Sports

[Forthcoming]