Nationality after World War II

Japan's bilateral talks with ROC and ROK

By William Wetherall

First posted 1 August 2006

Last updated 22 January 2022

Government, territory, people

Empire of Japan

•

Terms of surrender

•

Sovereignty, control, jurisdiction

•

Affiliation

•

Occupations and separations

Occupation Authorities

The Allied Powers as a supernational legal body

22 Mar 1952 DS notifies KDMJ that SCAP's jurisdiction will end

San Francisco Peace Treaty

The political watershed of postwar settlements with Japan

ROC and peace treaty

Negotiations between two states only one of which had been at war

ROK and peace treaty

Yang-Rusk exchanges

•

19 July 1951 Yang request

•

2 August 1951 Yang request

•

9 August 1951 Rusk reply

1951-1952 ROK-Japan talks

SCAP deems the legal status of Koreans in Japan the first and only priority

Personae dramatis

15 February 1952 conferees

Republic of Korea

Syngman Rhee

•

Yang You Chan

•

Yu Chin O

•

Karl Hongkee

•

Kim Yong Shik

•

Kim Dong Jo

•

Robert T. Oliver

Japan

Iguchi Sadao

•

Chiba Kō

•

Matsumoto Shun'ichi

•

Tanaka Mitsuo

•

Hiraga Kenta

•

Nishimura Kumao

United States

George Atcheson

•

Dean Acheson

•

John Foster Dulles

•

William J. Sebald

•

Alva C. Carpenter

•

Richard B. Finn

•

William H. Sullivan

•

Charles A. Willoughby

•

John J. Muccio

•

Dean Rusk and other American officials

Chronology

Meetings

1945 to September 1951

•

October 1951

•

November 1951

•

December 1951

•

January 1952

•

February 1952

•

March 1952

•

April 1952

ROK-Japan talk sources

Hiraga 1950-1951

•

Nik-Kan kaidan bunsho kai 2005

•

Sebald 1965

•

Sung-hwa Cheong 1990, 1991

•

Kim Dong Jo 1993

•

Kim Tae-gi 1997, 2011

•

Nantais 2011

•

Nishioka 1997

•

Ōnuma 1979-1980

•

Ōnuma 2004

•

Takasaki 1996

•

Takasaki 2004

•

Yi Yangsu 2007

•

Tae-Ryong Yoon 2008

•

Yoshizawa 2005

ROK and Japan archives

dongA.com zip and tif files

•

Nik-Kan Kaidan Bunsho Kai pdf and xdw files

•

Other sources

•

Most important ROK files

•

Most important Japan files

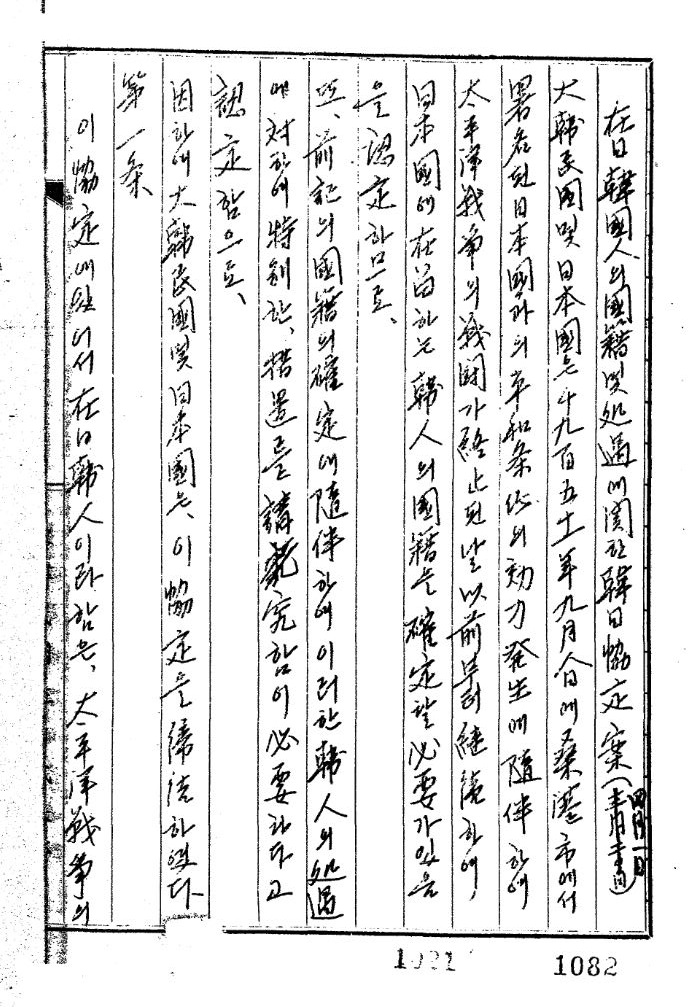

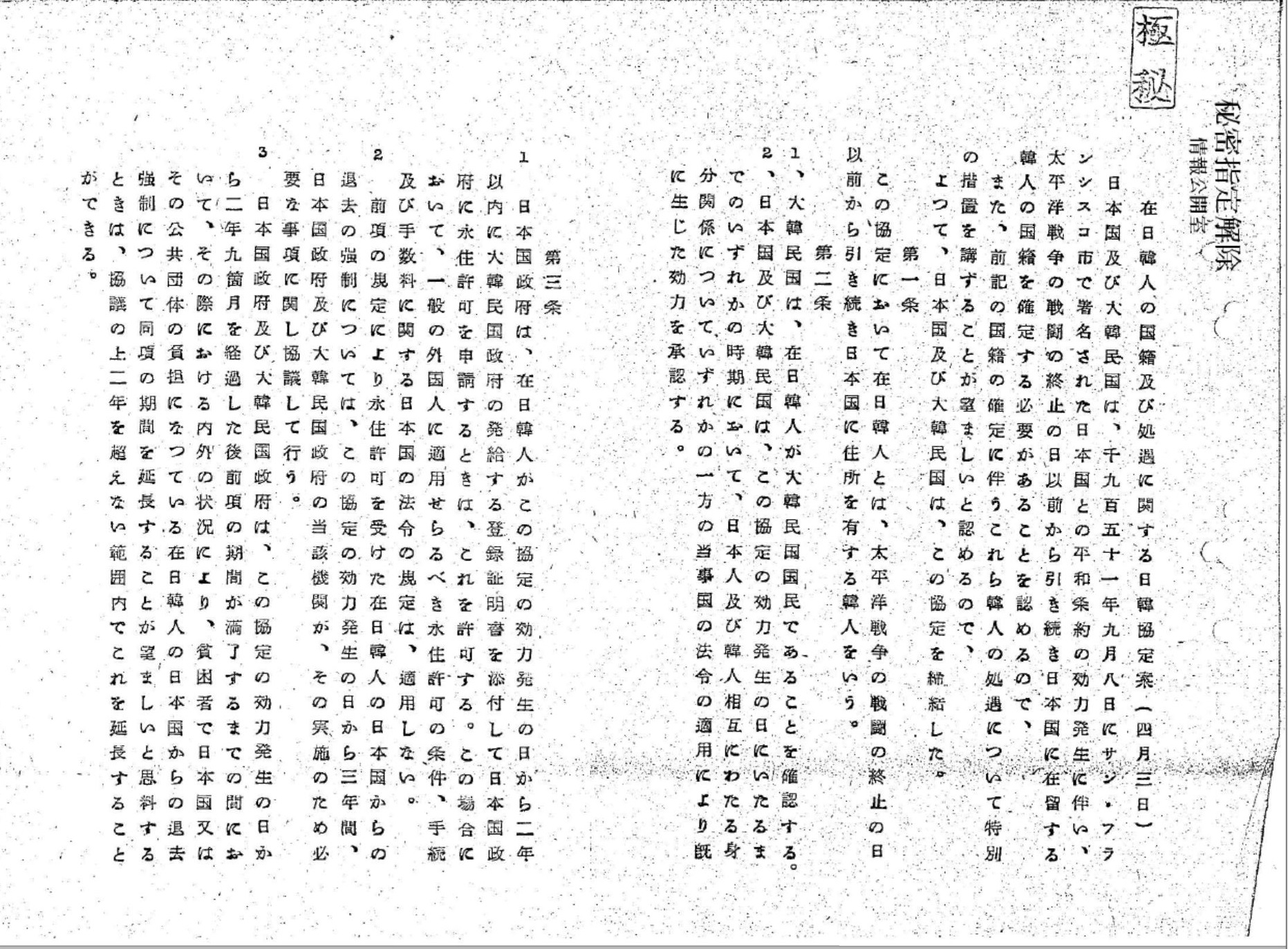

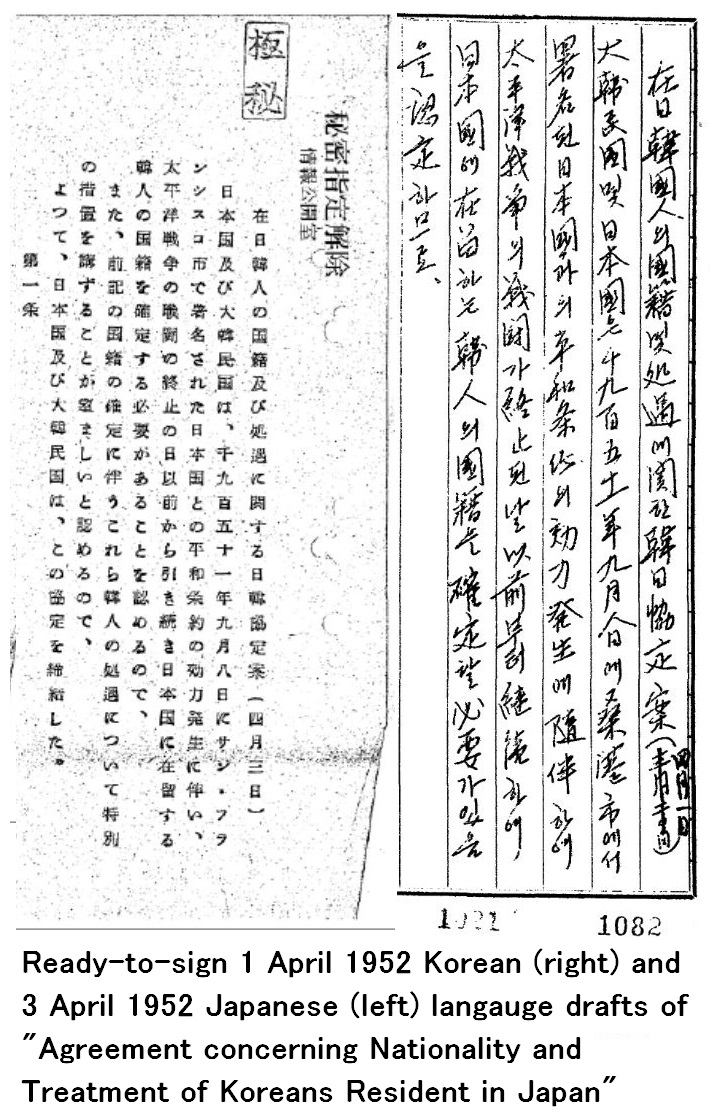

Status agreement drafts

Citations, transcriptions, translations, markup

•

Nik-Kan Kaidan Bunsho Kai activism

•

Yoshizawa et al. v. State

ROK Japanofile list

Related article

Separation and choice: Between a legal rock and a political hard place

Click to see full details below

Click to see full details below

|

Overview

Contentious but bilateral

Many people claim that Japan unilaterally separated Chosenese and Taiwanese form it's nationality in 1952 when the San Francisco Peace Treaty came into effect and Japan formally lost Chōsen and Taiwan as parts of its sovereign territory. Many writers also claim that Japan's actions in 1952 both violated international law and were illegal under its own domestic laws.

The following official English, Japanese, and Korean documents related to the 1951-1952 talks between Japan and the Republic of Korea (ROK), observed by officials of the Diplomatic Section (DS) and at times the Legal Section (LS) of the General Headquarters, Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (GHQ/SCAP) in Tokyo, show that these contentions are incorrect.

What Japan did in 1952 was in full accord with a ready-to-sign bilateral nationality and treatment agreement between the two states. The agreement took into consideration the recognition by Japan and the Republic of Korea (ROK), based on their often contentious discussion of nationality issues, that reciprocal nationality choice-provisions, of the kind that are commonly but not universally made when territories change hands, were not politically feasible in their case.

Nationality impasse

ROK was then at war with the Democractic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK). However, it held that it was the sole legitimate government of the entire peninsula, which it called Korea and not Chōsen. It also regarded all people in peninsula household registers as its nationals, and refused to acknowledge that they had ever been Japanese. However, under Japanese law, and in accordance with GHQ/SCAP's directives which recognized Japanese law, people in Chōsen registers had been Japanese, and Chosenese in Japan were still its nationals. Moreover, Japan would not force those who supported DPRK to be ROK nationals.

ROK and Japan circumvented this nationality impasse by agreeing that nationality did not qualify as a bilateral issue. The two states agreed that Koreans in Japan would be ROK nationals, though individuals would have to register their intent with an ROK legation in Japan. They also agreed to recognize the effects of their respective domestic civil status (household register) laws on nationality prior ro the coming into force of their nationality and treatment agreement.

Nationality territorial

Japan's recognition of Chosenese as ROK nationals, like its recognition of Taiwanese as ROC nationals, would be concomitant with their loss of Japan's nationality when Japan formally lost Chōsen (Korea) and Taiwan (Formosa). Japan's nationality had been, was then, and continues to be based entirely on whether one's primary domicile register (honseki 本籍) -- or household (family) register (koseki 戸籍) -- is affiliated with a municipal (village, town, city, ward) polity within Japan's sovereign dominion. Japan's nationality thus comes and goes with territorial cessions to and away from Japan. The loss by Chosenese and Taiwanese of Japan's nationality in 1952 is predicated on the separation of Chōsen and Taiwan from Japan pursuant to the SF Peace Treaty.

The suspension of Japan's nationality for people with domicile registers in Okinawa, concomitant with the suspension of Japan's sovereignty over the prefecture, during the period that it was administered under the control and jurisdiction of the United States, was based on the same principle.

Related article Separation and choice: Between a legal rock and a political hard placeGovernment, territory, and people

Understanding the legal settlements that followed Japan's surrender to the Allied Powers in 1945 -- especially those that determined the borders of states and reach of their nationality -- requires making clear distinctions between different kinds of governments and territories, and the statuses of people in governed territories. Governments include states and state-like entities which exercise absolute (sovereign) or qualified authority through their control and jurisdiction of one or more territories, the inhabitants of which are subject to a government's laws and regulations according to their legal status.

Empire of Japan

The Empire of Japan, as a state, consisted of territories that were part of its sovereign dominion, and other territories that were legally under its control and jurisdiction.

Sovereign Empire

At the time Japan surrendered, its sovereign dominion included the Interior or prefectures including Karafuto, and also Taiwan (Formosa) and Chōsen (Korea). Karafuto (southern Sakhalin) had been incorporated into the Interior as a prefecture in 1943. The Kuriles, which had belonged to Japan since 1875, were part of Hokkaidō. Hokkaidō and Okinawa, though governed somewhat differently than other prefectures and sometimes spoken of as though they were not part of the Interior, were in fact very much a part of the Interior as a subnational territory.

Legal Empire

Territories within Japan's legal dominion, but outside its sovereign dominion, included the Kwantung Leased Territory and the South Sea Islands. Russia had leased Kwantung from China in 1898 but transferred the lease to Japan in 1905. Kwantung was part of Manchuria, but after the creation in 1932 of Manchoukuo, mainly out of Manchuria, Japan regarded Kwantung as part of Manchoukuo rather than China. Russia had also given Japan its leases of right-of-ways and other land in the Railway Zone outside the Kwantung territory, but Japan's jurisdiction in the zone ended in 1937 with the end of extraterritoriality in the state.

Manchoukuo

Though Japan was instrumental in the establishment of Manchoukuo, and continued to wield enormous control over the state through its considerable involvement in the territory and its government, it regarded the entity as an independent state. As such, Manchoukuo was never part of the Empire of Japan. China continued to regard Manchuria as part of its sovereign dominion, and when the League of Nations sided with China, Japan resigned its membership. A number of other states, however, recognized Manchoukuo and established diplomatic ties with the entity.

Occupied territories

As of 2 September 1945, when Japan and the Allied Powers signed the general Instrument of Surrender in Tokyo, ending World War II in Asia and the Pacific, Japanese military forces were occupying or present in a number of territories in parts of China, Southeast Asia, and the Pacific, the result of both invations, and diplomatic relationships and manipulations, before and after the start of the Pacific War on 8 December 1941 Japan time. These territories were temporarily occupied by third-party Allied commands for the purpose of receiving Japan's surrender and facilitating an orderly transfer of power to the state having governmental rights under the terms of surrender or later treaties.

The Empire of Japan, however, did not include territories outside its sovereign dominion or legal control and jurisdiction. Manchoukuo, China, and countries like the Philippines -- as much as they had been subjected to Japanese military incursions and invasions, and partly or fully occupied by Japan, or partly under Japanese control after Japan established relations with them as states -- were never part of the Empire of Japan.

Terms of surrender

The terms of surrender set down in the Potsdam Declaration of July 1945 specifically referred to and thereby included the terms in the Cairo Declaration of November 1943. It did not refer to or otherwise include the Yalta Agreement of February 1945, as it was still secret. The general order issued at the time of the signing of the general Instrument of Surrender on 2 September 1945, however, included surrenders related to the Yalta Agreement.

Cairo Declaration

The Cairo Declaration of November 1943, issued by the United States, the Republic of China, and Great Britain, viewed Manchuria, Formosa, and the Pescadores as territories which Japan had "stolen from the Chinese" and would be "restored to the Republic of China".

The "Three Great Allies" which signed the declaration also determined that, "mindful of the enslavement of the people of Korea", Korea would "in due course . . . become free and independent".

The phrasing is extremely important, for it implies that China would recover its sovereignty over the "stolen" territories, while "Korea" was merely a territory -- not a state -- which, in time, would become a "free and independent" state.

Yalta Agreement

The Yalta Agreement of February 1945 -- between the Soviet Union, United States, and Great Britain, and implicitly endorsed by China -- was kept a secret until later in the war, because at the time it was signed, the Soviet Union was still bound by a neutrality pact it had concluded with Japan in April 1941.

The agreement provided that the southern part of Sakhalin and adjacent islands -- meaning Karafuto -- would be "returned" to, and the Kuril islands "handed over" to, the Soviet Union.

The lease of Port Arthur as a naval base would also be "restored" to the USSR, and other provisions for the protection of Soviet interests in the region -- while recognizing that "China shall retain full sovereignty in Manchuria".

Sovereignty, control, and jurisdiction

When signing the general Instrument of Surrender on 2 September 1945, Japan delegated the "authority of the Emperor and the Japanese Government to rule the state" to the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP), who was then General Douglas MacArthur.

"Formosa" and "Korea"

Japan continued to have control and jurisdiction in other parts of the formal and informal empire until the effectuation of local surrenders. These took place in Korea later in September, and in Taiwan in late in October.

Under the terms of surrender, Japan had agreed it would lose these territories. It lost effective sovereignty when it signed the general Instrument of Surrender in Tokyo, and it surrendered its actual control and jurisdiction when it surrendered the territories to designated Allied commanders -- the entirely of Formosa to the Republic of China, which claimed the territory -- and Korea by halves to the Soviet Union in the north and the United States in the south, which would occupy the peninsula until they could establish a Korean state to govern the territory.

However, Formosa and Korea were not formally separated from Japan's sovereignty until the provisions of the San Francisco Peace Treaty came into effect in April 1952. This lag between the loss of effective sovereignty in 1945, and the loss of formal sovereignty in 1952, effected the status of people in Occupied Japan whose family registers were affiliated with Formosa and Korea.

xxxx-1945/52Here and elsewhere, I have referred to the periods of Japan's sovereignty over Taiwan and Chōsen as respectively "1895-1945/52" and "1910-1945/52" to reflect the transition between (1) Japan's loss of control and jurisdiction over Taiwan and Chōsen pursuant to its formal surrender in 1945, and (2) the confirmation of Japan's loss of sovereignty over these territories pursuant to the effectuation of the San Francisco Peace Treaty in 1952. 2 September 1945 marks the start of the "dual status" of Taiwanese and Chosenese, who until 1952 were deemed "non-Japanese" or "aliens" for border control and alien registration purposes but remained "Japanese" for nationality purposes. Until this date, they were just Japanese with household registers in Taiwan or Chōsen. 28 April 1952 marks the end the legal grounds for Japan to attribute its territorial nationality to people in Taiwan and Chōsen household registers. The formal separation of Taiwan and Chōsen from Japan's sovereignty on this day became legal grounds for the separation of Taiwanese and Chosenese -- defined as people in Taiwan and Chōsen registers -- from Japanese nationality. |

"Japan"

The sovereign dominion of "Japan" as an empire, prior to its surrender, had included the Interior, Formosa, and Korea. But under the terms of surrender, "Japan" was reduced to an occupation zone defined as the Interior minus two prefectures -- Okinawa and Karafuto. The Kurile islands, which had been parts of Hokkaidō, and number of islands associated with Tokyo and Kagoshima prefectures, were also excluded from "Occupied Japan".

Japan, in its view, retained residual sovereignty over all parts of its Interior entity except Karafuto and the northern Kuriles. Japan continues to claim the southern Kuriles, which remain under the control and jurisdiction of Russia, and two small island groups, one claimed by the Republic of Korea, the other by the People's Republic of China.

Japanese government

"Occupied Japan" became the foundation for the "Japan" that signed a peace treaty with the "Allied Powers" in September 1951, according to which the Occupation ended and Japan regained its sovereignty in April 1952. During the Occupation, the imperial government of Japan continued to operate under its own powers, exercised under its own laws and regulations, limited and otherwise qualified only by SCAP directives.

The transition from an imperial government under the 1890 Constitution, to a post-imperial government under the 1947 Constitution, was effected in an orderly manner by the Japanese government itself. Many of the strings that animated the government were pulled by SCAP, especially during the early months of the Occupation. But most governmental strings continued to be pulled by duly elected representatives of "the Japanese people" by one or another definition.

SCAP, who held sovereign powers over Occupied Japan as an occupation zone, hitched the Japanese government to his General Headquarters. While GHQ/SCAP in principle governed Japan's national and local governments, it permitted these governments -- out of both political considerations and practical necessity -- to continue to operate under laws and regulations in force in Japan at the time its surrender, including the 1890 Constitution

SCAP nullified or revised only legal measures and related policies and practices, or disbanded or restructured only agencies or other offices, that conflicted with Allied reconstruction plans, such as they existed at the time Japan surrendered, and as they developed during the course of the Occupation. Government powers limited at the start of the Occupation were gradually restored as laws were revised to reflect the standards of government set down in the 1947 Constitution.

Negotiations with ROC and ROK

During the half year or so that elapsed between the signing of the peace treaty on 8 September 1951 and its enforcement from 28 April 1952, Japan regained effective control and jurisdiction over most of its domestic affairs. In preparation the restoration of its sovereignty, it also began to take charge of more its diplomatic affairs.

After Japan signed the peace treaty, GHQ/SCAP -- still formally an Allied authority but by then far more than originally an essentially American operation -- directed Japan to negotiate settlements with concerned states regarding Formosa (Taiwan) and Korea (Chōsen), and the status of Formosans (Taiwanese) and Koreans (Chosenese) in Japan, most of whom were still considered Japanese nationals. The concerned states favored by GHQ/SCAP were those the United States recognized, namely the Republic of China (ROC) and the Republic of Korea. These were also states with which the United States was allied in its own cold and hot wars against Communism.

The government of Japan, having been staunchly anti-communist and anti-socialist since the spread of proletarian movements in Japan during the early decades of the 20th century, and concerned about the spread of Communism in neighboring Asian states and subversive activities domestically, had no difficulty falling in line with the United States regarding ROC and ROK, both embattled with their revolutionary counterparts, the People's Republic of China (PRC) and the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK). ROC had lost its battle on the Chinese mainland and its government had taken refuge in the province of Taiwan, and at time it controlled only the province and a few islands affiliated with a mainland province. And ROK was embroiled in a fight for its life in a civil war with DPRK, which was supported by the People's Republic of China and the Soviet Union.

Japan and ROC, though their talks were touch and go, succeeded in negotiating a peace treaty the two states were able to sign on 28 April 1952, the day Japan regained its sovereignty and diplomatic powers. Japan and ROK also began, in the fall of 1951, to work out a normalization treaty and status agreement by the same date. But by early April 1952 negotiations had broken down to the point that they were deferred until after the peace treaty came into effect -- and the two states were unable to agree to terms until 1965.

Sovereignty and state succession

Ordinarily, territorial cessions are effected by treaties in which one state cedes part or all of itself to another state, which then becomes the successor state. And treaties involving territorial cessions usually include transitional provisions regarding the legal statuses, including the nationalities, of the people inhabiting affected territories.

However, Taiwan and Chōsen were not ceded away from Japan to other states. Rather they were separated from Japan by a third party -- namely, the Allied Powers -- and never formally ceded to "China" or "Korea". That ROC was a member of the Allied Powers did not itself matter. What mattered was that ROC, as the successor to the Chinese state which had ceded Taiwan to Japan, was the state which, according to the Cairo Declaration, stood to acquire Taiwan. Hence ROC was designated as the state to which Japan would surrender its control and jurisdiction of Taiwan, which ROC wold occupy and govern, and then incorporate as a province of its state.

Japan surrendered Chōsen, though, to the control and jurisdiction of two third-party Allied States, north and south of the 38th parallel. As in the case of Taiwan, Japan lost all say in the future of Korea (Chōsen) from the moment it signed the Instrument of Surrender. Until Japan and the Allied Powers signed a peace treaty, confirming the territorial provisions of the terms of surrender, Japan would retain de jure sovereignty for the purpose of attributing its nationality, but de facto sovereignty would be in the hands of the Allied Powers or the states which the Allied Powers recognized as the successor states.

Japan's abandonment of sovereignty over Taiwan and Chōsen under the terms of surrender, effective from 2 September 1945, was confirmed by the San Francisco Peace Treaty, effective from 28 April 1952. However, the treaty could not specify successor states, since after World War II the divided Allied occupation of Chōsen had resulted in the emergence in 1948 of two Korean states which claimed the peninsula and its population, and a civil war in China had resulted in the creation in 1949 of second Chinese state which claimed the same territory and population as the first. Never mind that ROC had both control and jurisdiction over Taiwan, and never mind that ROC was itself a major Allied Power, the other Allied Powers, divided over their recognition of ROC and PRC, agreed that ROC was no longer politically qualified to participate in the treaty.

Apart from the fact that the Allied Powers were also divided in their recognition of ROK nor DPRK, neither of these states had the legal capacity to participate, since they had not existed until after the war. In any event, Korea as Chōsen -- while a part of Japan which the Allied Powers had vowed to "liberate" from Japan -- had nonetheless, as part of Japan, not been at war with Japan. And at the time the San Francisco Peace Treaty was drafted and signed, the divided Koreas were at war, and the Allied Powers were divided in their military support of the warring states.

Not only could the San Francisco Peace Treaty not name successor states, it could not dictate which states Japan would have to provisionally recognize in order to negotiate appropriate treaties -- a peace treaty in the case of "China", a normalization treaty in the case of "Korea". However, for many reasons, Japan's logical political choices -- if political choices can be logical -- were to resume recognizing the Republic of China, established in 1912, and to newly recognize the Republic of Korea, founded in 1948.

The point, though, is that in 1945, Japan would be deprived of its de jure control and jurisdiction of Taiwan and Chōsen, and also of its de facto sovereignty over these territories. Then in 1952, when it also lost its de jure sovereignty, it would lose its right to ascribe its nationality to people in Taiwan and Chōsen registers. Everyone affiliated with these territories, meaning people enrolled in their household registers, had become Japanese through Japan's acquisition of sovereignty over them. Their Japanese nationality was linked with the status of these territories as parts of Japan of Japan's sovereign dominion.

From the day the peace treaty came into effect, Taiwan and Chōsen would be formally separated from Japan's dominion, and Japan would no longer have the legal right to recognize people affiliated with their population registers as it nationals. Japan would regard them as nationals of the states which the Cairo Declaration presumed would be the successor states.

Japan had actually lost its legal right to attribute its nationality when surrendering to the Allied Powers in 1945, because Japan had delegated its sovereignty to the Allied Powers. In other words, the Allied Powers had the right to determine whether Taiwanese and Chosenese had been, or would continue to be, Japanese. The Allied Powers, never mind the harsh wording of the Cairo Declaration, never doubted that Taiwanese and Chosenese had been Japanese, and as they foresaw an orderly legal restoration of Taiwan and Chōsen to "China" and "Korea" they deemed that the future nationality of Taiwanese and Chosenese would be determined by treaties.

As Japan would sign a peace treaty with ROC on the same day, ROC's nationality would be recognized, and hence most Taiwanese in Japan, who had already been enrolled in ROC's nationality under SCAP's authority and with Japan's acknowledgement, would be recognized as ROC nationals, while Taiwanese who had chosen not to be ROC nationals would also be classified as Chinese for alien registration and most other purposes. The nationality of Chosenese in Japan, however, would be merely "Chosenese" -- until which time Japan recognized a Korean state and permitted it to enroll Koreans in Japan who aspired to its nationality.

Cairo, Yalta, and Potsdam

On 15 August 1945, the emperor of Japan announced his acceptance of the terms of the Potsdam Declaration of 26 July 1945, and ordered the commanders of Japan's armed forces to cease hostilities. The Potsdam terms, which incorporated the territorial terms of the Cairo Declaration of 27 November 1943, became the terms of the Instrument of Surrender, which Japan signed on 2 September 1975. Some terms of the Yalta Agreement of 11 February 1945, including those concerning "the southern part of Sakhalin" and "the Kuril islands", also became part of the terms of surrender.

As an agreement between Japan and the Allied Powers, the surrender instruments had a number of immediate legal effects, two of which informed definitions of "nations" and "nationality" during the Allied Occupation of Japan.

1. Japan immediately lost all the territories specified (according to the Potsdam Declaration) in the Cairo Declaration, and "Japanese sovereignty [was] limited to the islands of Honshu, Hokkaidō, Kyūshū, Shikoku" and other minor islands as determined by the Allied Powers.

2. From the moment of surrender, "the authority of the Emperor and the Japanese Government to rule the state [became] subject to the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers", and the Allied Powers would continue to occupy Japan "until the purposes set forth in the Potsdam Declaration [were] achieved."

The Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers, otherwise known as SCAP, was corporalized in the body and will of General Douglas MacArthur (1880-1964) from 1945, and in his successors from April 1951 to the end of the occupation in April 1952. Much of SCAP's authority was delegated to and mediated by the higher officials at SCAP's General Headquarters in Tokyo -- or "GHQ/SCAP".

Process versus posturing

The aggressive language of the Cairo Declaration -- that Japan would be "stripped of" Taiwan and "expelled from" Korea -- expressed the goals of the Allied campaign against Japan. Coming as it did at the height of the war, this was little more than nationalistic posturing. In the event of victory, the process of "stripping" and "expelling" would be according to international law. The effects of the treaties that had caused Taiwan and Korea to become parts of Japan would have to be reversed through new treaties.

On the surface of the wording of the Instrument of Surrender -- reflecting, as in a hall of mirrors, the terms of the Potsdam and Cairo declarations -- it would appear that Japan had immediately lost not only its governmental control and jurisdiction over Taiwan and Chōsen, for example, but also its sovereignty over these territories. Potsdam and the instruments, though, provided only that Japan's sovereignty would "be limited to" the islands that constituted "Japan" as occupied by the Allied Powers.

As a matter of legal process, Japan did not formally "renounce" (abandon) all right, title, and claim to Taiwan and Chōsen, among other territories that were once part of its sovereign dominion, until Article 2 of the San Francisco Peace Treaty came into effect on 28 April 1952 -- from which date, according to Article 1, the Allied Powers recognized "the full sovereignty of the Japanese people over Japan and its territorial waters."

Under the authority of the Allied Powers Japan was expected to negotiate and sign a peace treaty. However, Japan's renunciation (abandonment) in the treaty of its sovereignty over Formosa (Taiwan) and Korea (Chōsen) would not be effected until it regained its own sovereignty under the same treaty.

The problem was that Formosa was under the control and jurisdiction, and effective sovereignty, of the Republic of China (ROC), while the People's Republic of China (PRC) claimed Taiwan as one of its provinces. And Korea was claimed by two states, the Republic of Korea (ROK) and the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), then at war. The Korean war had divided the Allied Powers in their support over one or the other Korea, and ROC and PRC, still confronting each other over their mutual claims to China, were also on opposite sides in the war.

Recognition politics, and conflicts over rights of succession, were not the only issues that prevented the participation of China or Korea in the peace treaty. ROK wanted to participate, but even if it had been the sole state on the peninsula, it had existed until 1948. Besides, the "Korea" which Japan would be renouncing in the treaty had been Chōsen -- i.e., part of Japan, and as such had not at war with Japan.

Consequently, no China or Korea was able to participate in the peace treaty with Japan, either as a state which had been at war with Japan, or as a state that needed to settle territorial and other issues with Japan. So Japan would have to negotiate separate treaties with one or the other or both of the states that claimed to be "China" and "Korea".

Settlement over Formosa (Taiwan) with ROC

On 28 April 1952, the very day its diplomatic powers were restored, Japan signed a peace treaty in Taipei with the Republic of China (ROC), according to it recognized that Taiwan was "under the control of" the ROC government. The Taipei treaty, in accord with the San Francisco treaty, did not specify ROC as the successor state, but merely recognized that ROC was the state then in control of the territory.

In 1972, Japan recognized the People's Republic China (PRC) as "China" and rescinded the 1952 treaty with ROC. However, Japanese courts continue to recognize the effects of the Taipei treaty until the change of recognition -- when, in the eyes of Japanese law, PRC became a state and ROC ceased being a state.

Settlement over Korea (Chōsen) with ROK

Apart from the fact that the two Korean states did not exist until 1948, there was no need for Japan to sign a peace treaty with any Korean state, since Japan was never at war with "Korea". Japan did, however, have to settle its territorial relationship with "Korea" as Chōsen.

At the time Japan signed the San Francisco Peace Treaty, on 8 September 1951, it informally recognized only the Republic of Korea (ROK). The following month, Japan, ROK, and GHQ/SCAP began discussing the legal status of Chosenese (Koreans) in Japan when the Peace Treaty came into effect the following year. At issue was the disposition of the Japanese nationality they still held under Japanese law, and what to do about Chosenese who did not migrate to ROK nationality.

Japan and ROK did not get around to normalizing their relationship until 1965. The normalization treaty is pursuant to "relevant provisions" of the San Francisco Peace treaty and certain United Nations General Assembly resolutions. The "relevant provisions" in the Peace Treaty included Japan's renunciation (abandonment) of all right, title, and claim to "Korea" -- which Japan understood to mean "Chōsen". The United Nationals resolutions provided the authority for Japan's recognition, in the normalization treaty, of ROK as "the only lawful Government in Korea".

The 1965 normalization treaty is the foundation of the 1966 agreement with ROK (promulgated with the treaty in 1965) concerning the status of ROK nationals in Japan who qualified for rights of abode according to Japanese laws that defined such rights pursuant to the Potsdam Declaration and the Instrument of Surrender.

The normalization treaty takes 15 August 1945 -- rather than 2 September 1945 -- as the date of the "initial determination" of the population that qualifies for rights of abode under the status agreement -- in acknowledgement of ROK's position that "Korea" was liberated on 15 August 1945. However, the "Special Permanent Residence" status created in 1991 for all treaty-defined aliens -- 25 years after the 1966 status agreement, which applied only to qualified ROK nationals -- adopts 2 September 1945 as the date of the "initial determination" of the residual population of former former Japanese subjects of Taiwan and Korea and others who lost their Japanese nationality because of the Peace Treaty and descendants born in Japan on or after 3 September 1945.

See Declarations and treaties: From Washington to San Francisco via the USS Missouri for introductions to, and full or partial texts of, all wartime and postwar declarations, agreements, instruments, and treaties from the Cairo Declaration to the San Francisco Peace Treaty.

See Territorial settlements: ROC and PRC, ROK and DPRK, and the USSR and Russia for introductions to, and full or partial texts of, major treaties and agreements between Japan and these entities, after the effectuation of the San Francisco Peace Treaty.

Affiliation

An individual's legal status is always complex. All people have a number of statuses defined by the laws of the country with which they are affiliated as nationals and/or in which they reside. The statuses of people in Occupied Japan were determined not only by applicable Japanese laws, but SCAP directives and legal provisions introduced in compliance with SCAP policy.

The Joint Chiefs of Staff in Washington, D.C. redefined the borders of "Japan" as an occupation zone to be governed by SCAP. It also redefined "Japanese" in such a way that partly alienated people whose family registers were under the control and jurisdiction of territories or polities outside the zone.

In a 3 November 1945 directive titled "Basic Directive For Post-Surrender Military Government In Japan Proper", JCS instructed SCAP to treat "Formosan-Chinese [sic] and Koreans as liberated peoples in so far as military security permits." They were excluded from the term "Japanese" as used in the directive, but SCAP was to treat them as "enemy nationals" when necessary. They could be repatriated if they wish, but priority was to be given to the repatriation of "United Nations nationals".

A 1 November 1945 GHQ/SCAP memorandum to the Japanese government (SCAPIN-224) concerning repatriation had spoken of "Koreans" and "Chinese" as "non-Japanese nationals" and alluded to people "formerly domiciled" in Formosa and the Ryukyus as though they might be "non-Japanese" by nationality. A 17 February 1946 memorandum (SCAPIN-746) more specifically listed "Koreans, Chinese, Ryukyuans and Formosans resident in Japan" as "nationalities".

By the end of 1946, there was considerable public confusion as to the status of Koreans who had remained in Japan rather than be repatriated by the 15 December 1946 deadline. GHQ/SCAP appears to have regarded them as "Koreans" or "Korean nationals" by "nationality" for classification purposes related to repatriation. Though "non-Japanese" in this regard, formally they would retain their Japanese nationality until treaties or other agreements determined otherwise.

GHQ/SCAP defined all manner of legal statuses that differentiated people in Occupied Japan, including whether one was a United Nations, enemy, or liberated national. Such statuses determined one's qualifications for food rations and other privileges, repatriation priority, and generally how one would be treated under measures introduced by Occupation Authorities.

GHQ/SCAP's directives concerning such statuses caused considerable confusion for the Japanese government, for Japan's laws made no such distinctions. No one was "non-Japanese" under Japanese law. There was territoriality (Interior, Taiwan, Chōsen) but no extraterritoriality. People who possessed Japan's nationality were Japanese, and those who did not were aliens. Chinese were aliens. Formosans (Taiwanese), Koreans (Chosenese), and Ryukyuans (Okinawans) were Japanese.

People, subjects, nationals

The English version of the general Instrument of Surrender signed on 2 September 1945 referred to "the Japanese people". The Japanese version referred to "Nihon-koku shinmin" (日本國臣民) -- or "Japan-country [Japanese] subjects" -- which included Taiwanese and Chosenese.

Subjecthood as such ended with the beginning of the Occupation, though as a legal category the word survived in a number of laws, including the 1890 Constitution, until they could be revised. The 1947 Constitution replaced the term "shinmin" with "kokumin" (國民、国民), meaning "national" but also reflecting the "the People" as used in the English version. This was not a new term, but one which had been used along with "shinmin" (subject) and sometimes "jinmin" (人民) or "people" since the early 1870s.

The term "nationality" (國籍、国籍 kokuseki) had been used to refer to state (national) affiliation since the 1899 Nationality Law. This law spoke of people who possessed Japan's nationality as "Japanese" (日本人 Nihonjin), reflecting conventions in legal terminology that also date to the early 1870s. The 1950 Nationality Law, reflecting usage in the 1947 Constitution, speaks of "nationals" rather than "Japanese".

GHQ/SCAP officials, however, spoke of "nationals" and "nationality" as defined by its own dictionary, which at times conflicted with the meanings of these terms in Japanese law.

Status and applicable law

Another wrinkle in the laws of all states is that nationals may be treated differently according to their affiliations with polities within the state. Most nationals of a country have multiple affiliations which subject them to territorial, including provincial and municipal laws, within the state's overarching jurisdiction.

Even non-nationals residing with a country as aliens are generally subject to the country's control and jurisdiction, unless they are protected by extraterritorial rights or diplomatic immunity. Whether an alien is subject to the laws of the country, or to those of another country, will also depend on the particular matter or incident, and determinations of laws of laws -- rules for determining applicable laws in cases of jurisdictional conflicts.

Nationals as aliens

Just as a state is free to differentiate among aliens, it is free to differentiate among its own nationals. A state may treat some aliens on a par with its nationals under some of its laws, and treat some nationals on a par with aliens under others.

No Japanese law during the Occupation of Japan classified Taiwanese or Koreans in Japan as as aliens. No law could have, for during the Occupation they remained Japanese. The 1947 Alien Register Order, for example, did not include Taiwanese and Koreans in its definition of aliens. It did, however, have a provision which stipulated that Koreans, and some Taiwanese, would be regarded as aliens for the purpose of the law. When the Philippines became a commonwealth protectorate of the United States in 1935, Filipinos remained non-citizen nationals of the United States, but exceptionally they treated as aliens under all US laws related to the immigration, exclusion, or expulsion of aliens.

GHQ/SCAP, as a military government, depended on the ability of Japan's legal system to continue to function. Accordingly, it had to take the established legal system into account when issuing directives that would affect the way the system worked. However, it is clear from its earliest directives on the treatment of what it called "non-Japanese" that it was not using terms like "national" or "nationality" in any way consistent with Japanese law. It was, in effect, imposing a new status system on top of an existing system. Japan was expected to treat so-called "non-Japanese" according to GHQ/SCAP's directives, yet under its own laws -- among Koreans, Chinese, Formosans, and Ryukyuans, which GHQ/SCAP was calling "nationalities" -- Chinese were "non-Japanese nationals" on account of their nationality.

During the Occupation, Japanese legislators had to come up with ways to reflect GHQ/SCAP directives in their revisions of Japan's laws. The laws had to be revised in ways that were consistent with Japanese law, while complying with GHQ/SCAP's rules.

In December 1945, as directed by GHQ/SCAP, revised its election law to include women and lower the age of eligibility to vote or hold office. A supplementary provision stipulated that only those subject to the Family Register Law, an Interior law, would be eligible. This in effect disenfranchised Taiwanese and Chosenese residents, who had previously been eligible.

GHQ/SCAP did direct Japan to exclude Formosans and Koreans from rights of suffrage. However, alienating them as "non-Japanese nationals" did not encourage their inclusion. Moreover, at this stage in the Occupation, when all it would have taken was a direct order on a single sheet of paper, GHQ/SCAP did nothing to reverse the effects of the supplementary provision -- which was, in any case, a well-established legal device for territorially limiting the reach of a national law.

Municipal halls and courts, and of course legislators, had to deal with problems of applicable law that arose because, despite the separation of a number of territories from Japan's legal control and jurisdiction, private matters involving individuals in Occupied Japan whose registers were in these territories would still need to be dealt with according to territorial laws of laws. Under Japanese law, people were in "Naichi" or "Taiwan" or "Chōsen" registers, but all three territories had been part of Japan. And because Japanese nationality was a matter of membership in a register within Japan, and all people in the registers of these three territories had been Japanese.

No treaties had yet made Taiwan and Chōsen foreign entities. They were no longer under Japan's control and jurisdiction, but Taiwanese and Chosenese in Japan reduced to the Occupied Interior were very much under Japan's control and jurisdiction. Yet they, like everyone else in Japan, was also under the control and jurisdiction of SCAP.

Japan had two laws of laws. One, introduced in 1898, concerned distinctions between Japan and other countries. The other, introduced in 1918, concerned distinctions between territories within Japan -- i.e., between Naichi, Taiwan, Chōsen, and other jurisdictions within the legal empire. Ryukyu, of course, was part of Naichi.

The knots that GHQ/SCAP tied in Japan's legal status ropes created headaches for those who had to handle them. Some indication of the difficulty in dealing with such knots that can be seen in a thick study, published in December 1949 by the Attorney General's Office of Japan, called Nihon ni zaijū suru hi-Nihonjin no hōritsu-jō no chii: Toku ni Kyōtsūhō-jō no Gaichijin ni tsuite or "Legal status of non-Japanese residing in Japan: Especially concerning Exteriorites under Common Law)". Undertaken from 1948 to 1949 by a judge doing research at the Judicial Research Institute, the study focused on the legal implications of SCAP's notion of "non-Japanese" (非日本人 hi-Nihonjin) in the light of Japan's Common Law, referring to the 1918 law of laws concerning applicable law within Japan's various legal jurisdictions.

Such studies were vital to the preparation required to deal with future legislation and litigation, which would have to take into consideration the effects of legacy laws. During the Occupation, though ordinances and regulations made for Taiwan and Chōsen were no longer applicable within these territories, they continued to apply within Japan in private (mainly civil, family) matters involving Taiwanese and Chosenese, whether with others Taiwanese or Chosenese, or with Interiorites, or with aliens regarded as such under Japanese law.

For details about the Attorney General's Office publication, see Legal status of SCAP's "non-Japanese" (Koshikawa 1949).

For details about the Japan's various laws of laws, see Status and applicable law.

Occupations and separations

Breaking up the Empire of Japan -- downsizing Japan -- separating from Japan the territories it would lose as parts of either its sovereign or legal dominion, and dealing with the territories it had invaded and -- was an extremely difficult undertaking, given the geographical spread of the formal empire, the sheer diversity of local conditions, and the numbers of states that would need to cooperate in the movement of people from where they were to where they were supposed to be or wanted to be.

Territorial separation was one problem. Separating and relocating people from territories (including countries or regions within countries) where they happened to be at the end of the war -- and determining their statuses whether they stayed or moved, and whether they did either by choice or because they had to -- proved to be a huge logistical challenge. When it was all over, several million people had been repatriated -- mostly back to Japan.

Occupied Japan as a dependency

When the Empire of Japan surrendered to the Allied Powers on 2 September 1945, it delegated its sovereignty to the Allied Powers. In doing so, it became very much like a dependency of another state, and as such it lost the quality of being an independent and sovereign state. In other words, like a dependency, Japan's statehood was suspended. The "state" on which Japan depended was the Allied Powers -- the collective "United Nations" which had declared war on Japan.

Dependencies typically delegate their diplomatic powers, among other matters of state, to another state, which acts as a proxy for the dependency. The Allied Powers, as victors with a mission to reconstruct Japan, agreed that the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, in the person of General MacArthur, would govern Japan for the purpose of carrying out the terms of surrender. As the sovereign authority in Occupied Japan, SCAP -- or officials he delegated, possibly even Japanese officials -- would act on Japan's behalf in all relations with other states and entities, until which time a joint peace treaty was signed and ratified by the Allied Powers, and Japan regained its sovereignty.

Occupations and separations in the Interior

As noted above the sovereign Empire of Japan included three territories -- the Interior, Taiwan, and Chōsen. The Interior consisted of 48 prefectures, including Karafuto, which had formally been integrated into the Interior in 1943. The Kuriles were part of Hokkaidō.

Legally, first the terms of surrender, and then the terms of the peace treaty, determined what parts of Japan were formally separated from Japan -- whether termporarily or permanently. Physically, however, separations were the effects of military actions, including invasions and occupations.

Parts of the Interior occupied by invasion

Before Japan announced its acceptance of the terms of the Potsdam Declaration on 15 August 1945, several parts of the Interior had already been invaded, captured, and occupied by American forces -- including Okinawa prefecture, some islands of Kagoshima prefecture, and some islands of Tokyo prefecture. By the end of August, the Soviet Union had occupied Karafuto and the Kuriles, which it began to invade on 9 August.

Practically all of these territories were excluded from the entity of "Japan" that the Allied Powers defined as the object of the Allied Occupation. Some were formally lost as a result of the San Francisco Peace Treaty (Karafuto, the Kuriles). Others continued to be administered by the United States for as long as two decades after the end of the Occupation (Ogasawara until 1968, Okinawa until 1972).

Parts of the Interior occupied peacefully

While "peaceful" may seem an inappropriate characterization of the occupation of most of Japan's Interior -- which had been subjected to horrifying air raids of unpreceded destruction to property and life -- as an occupation it was "peaceful" in two sense of the word -- (1) it took place after a cease fire and promise to surrender, rather than after being captured in a military invasion, and (2) it was a relatively amicable occupation in which victors and vanquished generally cooperated in the reconstruction what was remained of Japan and its government.

The entity of "Japan" as defined by the Allied Powers consisted, by and large, of the parts of the interior that were occupied peacefully after Japan announced its acceptance of the terms of the Potsdam Declaration. I.e., "Occupied Japan" consisted of the Interior minus the parts which had been captured and occupied following a military invasion.

Many parts of the rest of Japan too would have been bombed, invaded, captured, and occupied. had Japan not surrendered following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in the Interior. American forces, and probably some British Commonwealth forces, would have invaded several parts of Kyōshō, Shikoku, and Honshū. Soviet forces would have invaded Hokkaidō and the northern provinces of Chōsen. Some ports of Chōsen and Taiwan would have bombed. Probably only Taiwan would not have been invaded. Was was left of Japan would eventually have surrendered. But had the war continued for a another few months, the political map of East Asia today might be very different.

Planning the occupation of Japan

As it was, Japan signaled its willingness to surrender on 9 August, in principle ceased fire on 15 August, and generally surrendered on 2 September 1952. Some local surrenders had been effected long before 2 September, and several would take place later in the year. Some individual Japanese soldiers, who had gone into hiding in the jungles of islands where Japanese forces had been defeated, would not surrender until the 1970s.

Procedures for carrying out the terms of Potsdam Declaration, including the occupation of Japan's main islands, were established at the Manila Conference of 19-21 August. Advanced contingents of US forces began arriving in Tokyo and Kanagawa a week later. MacArthur arrived on 30 August.

The Instrument of Surrender -- marking the formal start of the surrender and occupation of the entire Empire of Japan -- was signed on the deck of the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay on 2 September 1945.

The surrender and disarming of Japanese military forces within the main islands of Japan took a few weeks.

Surrenders in other Japanese territories

On the day the Instrument of Surrender was signed aboard the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay, and pursuant to their terms, the Imperial General Headquarters of Japan issued orders for the surrender of Japanese forces and agencies everywhere they were known to exist. The order -- which stipulated which commander of which Allied Power was responsible for receiving Japan's surrender in which country or territory -- came from the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) in Washington by way of the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP) in Tokyo.

The surrender of Japanese forces beyond the Interior took a few months. The sovereign Empire of Japan included, in addition to the prefectural Interior (内地 Naichi), the legally distinct territories of Taiwan (台湾) and Chōsen (朝鮮). These were informally called "external territories" (外地 gaichi) in that they were outside -- i.e. not yet part of -- the prefectural Interior (内地 Naichi), hence not subject to Interior laws unless the laws were specifically extended to them.

Two other external territories -- the Kwantung Leased Territory, which was formally part of China but under Japan's legal control and jurisdiction -- and the South Sea Islands, which Japan was legally administering under a League of Nations mandate -- were part of Japan's legal empire but not part of its sovereign empire.

In addition to these territories, all legally part of Japan, there were several territories in which Japan had established governmental facilites or military bases, either peacefully (e.g., Vietnam and Thailand) or by invasion (e.g., China and Burma).

Peaceful occupations of other parts of Japan

While the occupations of all parts of Japan were important for people effected by them, the most important occupations were those of the largest -- Chōsen and Taiwan.

The occupation of Chōsen (Korea)

The Soviet military occupation of the northern provices of Chōsen, while not a military invasion, was reported much rougher on Japanese inhabitants, both Chosenese and Interiorites, than in the southern provinces, occupied by the US forces. Both occupying powers set up provisional governments, the north a communist regime, the south a nationalist regime. Both provisional governments were headed by Koreans who had participated in and led resistance movements beyond Japan's reach.

Japan's sovereignty over "Chōsen" was supposed to revert to "Korea" -- but there was no "Korea" in 1945 when the peninsula was occupied in the south by the United States and in the north by the Soviet Union. The failure of the US and the USSR to unify the two occupation zones, and create a single state with effective control over the entire peninsula, resulted in the founding of two Korean states in 1948 -- the Republic of Korea (ROK) in the US occupation zone, and the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK) in the Soviet zone.

Both Korean states claimed to be the true government of the "Korea" from which the Cairo Declaration promised to "expel" Japan. During the Allied Occupation, however, Japan followed the United States and the largely US-inspired United Nations recognition of ROK -- and subsequently normalized its relationship with ROK while confirming its view that ROK was the only lawful government in or on "Chōsen" (Japanese version), "Korea" (English version), or "the Korean peninsula" (ROK Korean version).

ROK not qualified to join peace treaty

Even if the peninsula had not been divided into occupation zones which resulted in the founding in 1948 of two Korean states that by 1950 were at war -- a united, peaceful Korea would not have been qualified to join the peace treaty signed by Japan and the Allied Powers in San Francisco in 1951. The Allied Powers different in their recognition of ROK and DPRK, and in their view of whether either or both states should be party to the treaty.

The United States, however, refused to accept claims by Korean nationalists that Korea had never belonged to Japan. It also refused to entertain demands by those returning from exile, like Kim Ku, then president of the "Korean Provisional Government" (KPG) founded in Shanghai in 1919, should be immediately recognized as the legitimate government of a "liberated" Korea.

Japan's annexation of Korea as Chōsen had in fact been recognized by all of the Allied powers. Even during the war, and despite the rhetoric of the Cairo Declaration, none of the Allied powers had recognized KPG -- except ROC, but only after it had fled from Nanking (Nanjing) to Chungking (Chongqing) in virtual exile within China.

KPG too, under the leadership of Kim Ku (金九 김 구 1876-1949), had fled from Shanghai to Chungking, where it joined ROC in declaring war on Japan and Germany after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on 8 December 1941 (East Asia time). Kim, KPG's president since 1927, pledged its "Korean Liberation Army" to local resistance against Japan, and was about to take the war to Korea, as the USSR had taken it to Manchuria, when Japan surrendered.

On the advice of Chiang Kai-shek, MacArthur invited Kim Ku, as well as Syngman Rhee (1875-1965), KPG's first president from 1919-1925, to come to Korea and help put together a government. Kim lost to Rhee in ROK's first elections, held a month before the formal founding of the state on 15 August 1948.

ROK, though immediately recognized by the United States, the Republic of China, and a number of other members of the United Nations who were opposed to communism, was generally not regarded as qualified to join the peace treaty with Japan for reasons having little to do with recognition politics. There had been no Korean state in the eyes of the world at large since 1910. No Korean stated existed in January 1942 when the Allied Powers, calling themselves the United Nations (not the later United Nations), declared war against the Axis powers and vowed to sign a common peace treaty with Japan. Throughout the war, what the Allies called "Korea" had not been a belligerant against Japan but an integral part of Japan.

The Allied Powers did not recognize that KPG -- never mind KPG's declaration of war against Japan, and its boasts of having supported resistance operations against Japan -- had represented "Korea" as a state, much less been a member of the Allied Powers.

No retrocession and no successor state

Unlike conventional territorial transfers, which take place between two states, "Chōsen" was separated from Japan by a treaty between Japan and the Allied Powers, which did not -- because it could not -- designate a successor state. Japan was not given an opportunity to retrocede Chōsen to "Korea" or any other successor state. Japan had no say in the disposition of "Korea" -- except to renounce its claims to Korea (Chōsen) to 48 3rd-party states.

p>In the meantime, the "Korea" that Chōsen should have become ended up divided into two states -- the Republic of Korea (ROK) in the south, and the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK) in the north. Given the build-up of tensions in the region, I would argue that these two states -- apart from the fact that Soviet-supported DPRK invaded America-supported ROK, thus firing the first shot -- were bound to end up fighting over the half of Korea both claimed but didn't control.For Chosenese north and south, the divided occupation of the peninsula was a nightmare in the making. For Chosenese in Japan, the separation of "Chōsen" from Japan without the agency of a bilateral treaty between Japan and a Korean state meant that -- when losing Japanese nationality on 28 April 1952 -- they were left with no state affiliation -- or, as I would put it, a would-be nationality without a state.

Taiwan and the Pescadores

Taiwan and the Pescadores (澎湖 Penghu), which is what I mean when I say Taiwan, was the diametri opposite of Chōsen when it came to surrender and occupation. Unlike Chōsen, Taiwan had a Chinese state waiting to accept its return to China -- the Republic of China -- an major Allied Power no less.

ROC, representing the Allied Powers, accepted Japan's surrender in Taiwan on 25 October 1945. As the Cairo Declaration, embedded in the Potsdam Declaration, had designated ROC was the suggessor state, ROC, not waiting for a treaty, immediately incororated Taiwan back into China, 50 years after the government of China under the Ching (Qing) Dynasty had ceded the territory to Japan.

ROC expected to participate in the San Francisco Peace Treaty, and would have, if it had not been driven off the mainland in 1949 by the People's Liberation Army after the founding of the People's Republic China that October. The Allied Powers could not agree over ROC's representation, hence the treaty allowed Japan to merely renounce its claims over Taiwan -- without any designation of a successor state. Japan, when signing an independent peace treaty with ROC on 28 April 1952, the day Japan regained its sovereignty and right to conduct its own foreign affairs, was unable to retrocede Taiwan to ROC because it was no longer Japan's territory.

Taiwanese in Occupied Japan were allowed to enroll in ROC nationality, and most had thereby become ROC nationals also in SCAP's and therefore Japan's eyes, long before the revolution on the mainland drove the ROC government into exile in Taiwan. Consequently, they became affiliated with a state with which Japan immediately normalized it relationship.

The separation of Taiwan from Japan de facto in 1945 and de jure in 1952 -- and the separation of Taiwanese from Japanese nationality in 1952 -- does not seem to have caused Taiwanese in Japan a great deal of grief. The occupation of Taiwan by the ROC government in exile in 1949 was arguably more traumatic for Taiwanese in Taiwan than the relatively peaceful conditions which existed in the territory under Japanese rule in the 1920s and 1930s.

When becoming ROC nationals, Taiwanese in Japan acquired the status of United Nations nationals, which means they had three statuses. When the San Francisco Peace Treaty came into effect in 1952, they lost two of their statuses -- as United Nations nationals and as Japanese -- and became simply aliens of ROC nationality.

The loss of Japanese nationality and the recognition of alien status in 1952 were formalities related to the end of the Occupation and Japan's rebirth as a sovereign state. For during the Allied Occupation, Taiwanese in Japan had already become ROC nationals and were essentially treated as such under Occupation law. In the meantime, Japanese law continued to associate Japanese nationality with Taiwanese registers until Taiwan was formally separated from Japan.

Japan's and ROC's relations were such that ROC nationals -- most of them Taiwanese rather than mainland nationalist refugees -- were generally welcome in Japan. Most spoke Japanese, and had recently themselves been Japanese, and even those who had never been to the prefectures would not have felt entirely like fish out of water.

Even after Japan switched its "China" recognition from ROC to PRC in 1972, relations between the two states remained cordial. Though formally Japan could no longer regard ROC as a state, it continued to treat ROC nationals pretty much the same way when it came to issuing permits to enter or stay in Japan. Moreover, ROC nationals who had settled in Japan had no difficulty plying between Japan and ROC.

The switch of recognition in 1972 resulted in a sudden jump per year, in 1972 and 1973, of about 6,000 applications for permission to naturalize -- from ROC nationals who had obtained certificates of renunciation of ROC nationality in advance and become stateless shortly before the recognition change. During the early 1970s, well over 12,000 ROC nationals in Japan were permitted to naturalize in what remains the most dramatic leap in the naturalization rate in Japanese legal history.

See Naturalization under the 1950 Nationality Law for statistics and commentary.

Karafuto and the Kuriles

The Soviet Union, also in lieu of a treaty, similarly treated the Kuriles and Karafuto as part of its sovereign territory. In 1875, Japan and Russia resolved their claims over the southern part of Sakhalin (Karafuto) and the northern Kuriles by agreeing that all of Saghalin would belong to Russia and all the Kuriles to Japan. Then in 1905 Russia had ceded Karafuto (southern part of Sakhalin) to Japan.

While Japan has recognized its loss of Karafuto, it claims that, in signing the San Francisco Peace Treaty, it did not intend to cede its sovereignty over the southern Kuriles, which had not been contested by Russia in 1875. Though Japan and the USSR normalized their relationship in 1956, the two countries -- the USSR as Russia since 1991 -- have yet to sign a peace treaty, on account of their continuing disagreement over what Japan has called its "Northern Territories" since the 1960s.

and had, which the Soviet Union began to invade on 9 August 1945, had been occupied by 28 August which the Soviet Union had invaded before the announcement of surrender, were fully occupied were u to had already invaded, were under and The surrendered, it had lost control of Okinawa and all these territories when it surrendered -- Korea when Japan surrendered Chōsen south of the 38th parallel to the United States and north of the parallel to the Soviet Union -- Taiwan when Japan it was surrendered to and occupied by the Republic of China, and Karafuto and and the Kuriles when they were invaded and occupied by the Soviet Union.

Non-sovereign territories of Japan

In addition to territories that were formally incorporated into Japan's sovereign dominion, a number of territories were under Japan's effective legal control and jurisdiction.

Kwantung Leased Territory and Railway Zone

Japan's sovereignty did not extend to the Kwantung Leased Territory or the Railway Zone. Originally these territories were leased from China, then from the Republic of China. From the mid 1930s, however, Japan took the position that they were part of Manchoukuo, which it considered an independent state, and so Manchoukuo replaced ROC as the lessor state.

These territories -- including "Manchuria" (as the Allies referred the part of China that had become "Manchoukuo") -- were invaded and occupied by the Soviet Union. By mid 1946 the USSR had transferred control of all of Manchuria to ROC -- except what it considered its continuing interests in the Kwantung leased territory, particularly Port Arthur. ROC agreed to a Soviet plan to jointly operated an area about the size of Kwantung called the Port Arthur Naval Base District.

China was then divided by civil war, and by 1948 most of Manchuria was under communist control. In USSR eyes, China became the People's Republic of China in 1949. In 1955, the USSR returned its Port Arthur interests to PRC and withdrew its military forces from the area.

South Sea Islands

The South Sea Islands, formerly German outposts in western Pacific, were administered by Japan under a League of Nations mandate. Japan continued to discharge this mandate after its formal withdrawal from the league.

Many of the mandate islands were invaded, captured, and occupied by the United States during its Pacific operations. Most of the islands were later administered by the United States under UN mandates.

Countries occupied by Japan or under Japanese influence

When the war ended, a number of countries -- though not formally part of the Empire of Japan [double hyphen]were under Japanese control or influence. Japan was involved in the affairs of Manchoukuo, China, and Vietnam before the start of the Pacific War. Other countries, like the Philippines and Burma, had been been invaded and occupied by Japan during the Pacific War

During the war, Japan restructured several of the countries it partly or completely occupied as nominally independent states which joined Japan's declaration of war against the Allied Powers. Examples include the National Government of China under Wang Jing-wei and the Republic of the Philippines under José P. Laurel.

Manchoukuo

Manchoukuo represented a different situation, in which Japan helped create a new state out of territories that had been contested by China and Russia, then by the Republic of China and the Soviet Union. Japan's actions in setting up Manchoukuo seeded the diplomatic hostilities that grew the conflict that began between Japan and ROC in 1937 and exploded in Pearl Harbor and the Pacific War in 1931.

Manchoukuo, despite all the posturing by the Republic of China and its supporters in the League of Nations, actually functioned as state. The considerable influence which Japan had over Manchoukuo could be characterized as "control" but not "jurisdiction" -- as Japan had resorted to all manner of legal ruses to showcase Manchoukuo as an independent country.

The other Allied Powers supported China's claim that "Manchoukuo" did not exist except in Japan's imagination. Like China, called the region "Manchuria" in English and considered it an "occupied" territory that had to be "liberated" from Japanese control.

Because Japan had never claimed Manchoukuo, and since it was never otherwise a part of the Empire of Japan, greater Manchuria was never the object of a treaty of cession with Japan.

China

The object of Japan's expansion in China was to rescue the country from the inability of its territorial and ideological war lords to put aside their differences in order to build a strong, prosperous, peaceful, and friendly China. Japan was particularly plagued by civil unrest along China's border with Manchoukuo, which China claimed Japan had illegally established in territory that rightfully belonged to China.

Aside from whether the establishment of Manchoukuo in Manchuria in 1932 constituted an occupation of China, Japan's actions in China from 1937 undoubtedly constituted a military invasion and occupation of some of China's major provinces, ports, and cities, beginning with its northern and southern capitals.

That Japan signed a peace treaty with the Republic of China in 1952 was a bit ironic. Japan had never declared war on China. ROC had declared war -- but not in 1937 when Japan invaded and occupied parts of China -- and not in 1938, after the ROC government went into exile in Chungking (Chongqing) -- and not even in 1940, when Japan recognized the Chinese government of Wang Jing-wei -- but only after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, when it ROC joined the United States in its declaration of war against Japan. And then, of course, ROC became one of the major Allied Powers in their prosecution of the war against Japan.

Article 26 of the San Francisco Peace Treaty imposed the following obligation on Japan.

Japan will be prepared to conclude with any State which signed or adhered to the United Nations Declaration of January 1, 1942, and which is at war with Japan, or with any State which previously formed a part of the territory of a State named in Article 23, which is not a signatory of the present Treaty, a bilateral Treaty of Peace on the same or substantially the same terms as are provided for in the present Treaty, but this obligation on the part of Japan will expire three years after the first coming into force of the present Treaty. Should Japan make a peace settlement or war claims settlement with any State granting that State greater advantages than those provided by the present Treaty, those same advantages shall be extended to the parties to the present Treaty.

To add to the irony -- by 1952, the ROC government no longer had control over the "China" which Japan had partly invaded and occupied. It had taken refuge in, and controlled only what had legally been part of Japan until ROC received the surrender of Taiwan in 1945 -- plus a couple of islands, which were part of Fukien province, which ROC had fortified to discourage PRC from attacking it across the straits.

Japan's signing of the Taipei Peace Treaty with ROC was almost as though it was signing a peace treaty with itself.

Southeast Asian countries

The object of Japan's military invasions of Southeast Asian countries was to liberate them from the American, British, and Dutch powers that were not only controlling their governments and economies, but were denying their port facilities to Japanese ships if not using their ports as bases for naval blockades of Japanese shipping routes.

All these countries were in turn "liberated" from Japanese control or influence -- some, like the Philippines, in bloody battles, others in peaceful transfers of authority after Japan's unconditional surrender.

Occupation Authorities

Understanding the legal workings of the Allied Occupation of Japan, and of occupations of other territories that were part of the Empire of Japan, and of all postwar settlements, including the San Francisco Peace treaty, requires recognition of the fact that the Allied Powers constituted a supernational legal body since their joint declaration of war as the "United Nations" against Germany, Italy, and Japan on 1 January 1942.

William Sebald on the Occupation as an "international enterprise"

William Sebald, who arrived in Occupied Japan in January 1946 to begin his assignment to POLAD as an expert on Japanese law, describes the office like this in his autobiography, With MacArthur in Japan: A Personal History of the Occupation (New York; W.W. Norton & Co., 1965, with Russell Brines) (Sebald 1965, page 42).

Although the State Department had participated in preliminary planning [for the Occupation], its role in Tokyo at this period of the Occupation was limited and only vaguely defined. Our office was known as Acting United States Political Adviser to SCAP [Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers = General Douglas MacArthur], shortened to POLAD. Headed by the late George Atcheson, Jr., with the personal rank of minister, it operated in many ways like an embassy accredited to the Occupation. This was consistent with the legal concept of General MacArthur as supernational representative of an Allied occupation. But, in fact, the Occupation never became an international enterprise, despite the involvement of all eleven wartime associates [Great Britain, Republic of China, Soviet Union, et cetera]. Instead, SCAP was predominantly American in operation, as well as in personnel, to the discomfiture of several Allied governments. The position of POLAD, therefore, was in the beginning curiously half in and half outside the mainstream of Occupation affairs.

Sebald had been a Japanese language officer with the U.S. Navy in Japan in the mid 1920s, and had practiced and translated law in Kobe in the 1930s before being suspected of spying on Japanese naval operations and forced to Japan in 1939. He quickly became Atcheson's assistant, and would himself head POLAD after Atcheston died in plane crash in August 1947. He then became the Chief of the SCAP's Diplomatic Section, and would be involved in many of Japan's diplomatic affairs for the duration duration of the Occupation -- including Japan's talks with ROK.

Sebald, bilingual and legally minded, and a quick student of diplomacy, clearly perceived the legal responsibilities of the Allied Powers as an Occupation Authority. There were numerous examples of how victors had treated the vanquished in the past, and many precedents regarding the disposition of the nationality status of inhabitants of transferred territories and of displaced people -- people who ended up in a territory to which they would no longer legally belong.

I have no evidence of the extent to which Sebald was involved in the drafting of POLAD's "Status of Koreans in Japan" report -- but I would guess that he at least read it and approved.

Far Eastern Commission

The Far Eastern Commission (FEC) was established to oversee the multiple occupations of the territories of the Empire of Japan, including the parts of the prefectural Interior that became Occupied Japan. In principle, SCAP was subject to FEC's control and obliged to carry out its directives.

The "eleven wartime associates" Sebald mentions in his statement about how the Allied Powers intended to oversee SCAP in Occupied Japan refer to the following FEC members.

United States of America

Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

United Kingdom

[Republic of] China

France

The Netherlands

Canada

Australia

New Zealand

India

The Philippine Commonwealth

The 4 first listed powers -- the "Big 4" -- had veto powers over a majority of the other powers. But the arrangement didn't work, mainly (but not only) because of disagreements between the United States and the Soviet Union.

The Americanization of history

Some historians call the Occupation of Japan the "American Occupation" and a few even characterize the San Francisco Peace Treaty as a treaty between Japan and the United States. Whatever the extent of America's control of the Occupation, and of American say in the drafting of the Peace Treaty, both were nonetheless legally -- under international conventions of postwar settlements -- "Allied" enterprises.

The Allied Powers constituted the equivalent of what Sebald properly characterized as a "supernational" body. If asked for clarification, he would have said a body with powers equivalent to those of state -- or even dictatorship -- over an occupied entity. The terms of surrender suspended Japan's sovereignty and subject the government of Japan to the absolute authority of the Allied Powers, represented by SCAP -- the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers. SCAP, though, was not the supreme authority within the Allied Powers. Whoever sat on SCAP's throne -- initially Douglas MacArthur -- was in principle, if not always in practice, subject to the larger collective authority of the Allied Powers.

The point, though, is that the Allied Powers were a source of law and enforcement unto themselves. Most the members of the Allied Powers were founding members of the United Nations. And it is no co-incidence that the major Allied Powers, following their victories in the European and Pacific theaters of World War II, dominated the United Nations in its earlier years.

22 March 1952 DS notifies KDMJ that SCAP's jurisdiction will end

On 22 March 1952, the Diplomatic Section of GHQ/SCAP informed the Korean Diplomatic Mission in Japan -- in what appears to be a form letter that DS probably sent to all diplomatic missions in Occupied Japan -- that SCAP's jurisdiction would soon end pursuant to the imminent effectuation of the Allied Peace Treaty with Japan. Upon the restoration of sovereignty to Japan and its people, KDMJ would be on its own regarding its relationship with Japan. SCAP would no have the authority to mediate.

The following text is my transcription of a scan of a copy of DS's 22 March 1952 communication to KDMJ in ROK archives (KRN 82: 138). See ROK and Japan archives for source particulars.

|