Status and applicable law

Governing the civil affairs of territorialized people

By William Wetherall

First posted 1 August 2008

Last updated 28 April 2021

Jurisdiction and applicable law

International private law

•

Law of application

•

Law of personal affiliation

Affiliation and status

Country of nationality

•

Place of domicile

•

Place of habitual residence

•

Status and capacity

Laws of laws

1890 Rules of Laws

•

1898 Rules of Laws

:

Revisions

:

1948 revision

:

2000 revision

•

2007 Common Rules Law

1918 Common Law

Interior, Chōsen, Taiwan, and Karafuto in Imperial Japan's territorial domestic laws of laws

Issues in 1898-2007 laws

Two or more nationalities

•

No nationality

•

Taiwan, Hokkaido, Okinawa etc.

•

Karafuto

•

Chosen

Divided Korea in Japan today

Neither ROK nor DPRK recognized

•

Only ROK recognized

•

Both ROK and DPRK recognized

Related articles

1872 Family Register Law

Marianne's custody dispute, 1956-1958

Cho Kyongje on "Personal law of Koreans in Japan"

Jurisdiction and applicable law

"Territorialized persons" is my term for people who are viewed as legally affiliated with a territory, for whatever reason. A person's territorial affiliation -- whether for purposes of "subjecthood" or "nationality" or "citizenship" or "residence" -- is commonly a factor in how the person will be treated as a "natural person" or "corporate person" under one or more territorial laws.

This section concerns "jurisdiction" and "applicable law" when multiple territories -- and generally multiple territorial affiliations -- are involved. The next section covers various definitions of the "affiliation" of "natural" and "juridical" (legal) persons for the purpose of determining jurisdiction and applicable law.

As all these matters are interrelated, there will be some repetition. I will begin each section with some general observations that I do not intend to be rigorous, and which legal scholars will probably view as evidence of my ignorance about a field of law that even lawyers find nightmarish.

After making general observations, I will focus on jurisdiction, applicable law, and affiliation in the Empire of Japan, when Japan had as many as six legal jurisdictions. All this will serve as a preface for introducing the 1918 Common Law, which concerned applicable law in private matters among people affiliated with these jurisdictions.

In a nutshell

To avoid conflicts between legal entities, such as states and their various organs and agencies, laws are needed to determine which entity has responsibility or jurisdiction in a given matter, but laws are also needed to determine which entity's laws are applicable to the matter.

Jurisdiction may be defined as the geographic or demographic reach of a legal authority such as a government, police force, or court. Such authorities, as law-enforcement bodies, are guided by laws that determine which laws they are authorized to enforce, and where and with regard to whom they are authorized to enforce these laws.

Someone may commit a crime in one territory and flee to another territory. The two territories might be sovereign states, and perhaps they have agreements concerning the cooperation in investigation, apprehension, and extradition of suspects. Or the two territories are different jurisdictions within the same sovereign state, and are subject to national or territorial laws concerning how national or territorial authorities deal with a criminal or civil case or private matter.

Agreements and laws of this kind are intended to eliminate or at least minimize conflicts arising over, say, the right of an agency of one entity to within another agency's or entity's jurisdiction, or which entity or agency has control in jurisdictions where they have agreed to work together.

Applicable law refers to the laws with which individuals or entities are supposed to comply -- or, in turn, to the laws that a legal authority feels obliged to apply in the course of carrying out its lawful responsibilities. The term is essential to discussions of what laws a court determines should apply in the hearing and judgment of a particular case. A law of laws is a set of rules for determining which laws should apply in to matters between parties, whether natural or juridical persons.

Courts of law constitute a legal marketplace. The laws of laws of multi-state entities, like those adopted by the European Union, seek to eliminate or minimize differences in the ways member states determine applicable law, in order to prevent what is called "forum shopping" -- in which a party takes a dispute not to the court best situated to settle the matter, but to a court which applies a law that favors the party's position. "Forum shopping" is on a par with seeking to live or conduct business in a place with more benefits, such as lower taxes, less restrictive regulations, or better welfare benefits.

A personal comment on the nature of laws

Laws are standards -- rules and regulations -- for guiding behavior and action. Penal codes guide actions taken by a government against behaviors it considers criminal. By providing that people will be punished if found guilty of proscribed behaviors, penal codes also have the effect of deterring at least some people from committing the stipulated offenses.

Civil codes guide actions in family and other social matters, and commercial codes set standards for business practices. Such codes both set standards for proper procedure, and prescribe punishments if someone fails to comply legal requirements. Some acts that contravene civil and commercial codes may also be criminal.

Such laws are generally designed to operate within specific governmental jurisdictions -- a village, a district, and entire country, possibly a group of countries. All manner of other kinds of "legal bodies" -- organizations, corporations, associations -- have their own laws by which they govern their own operations. "House rules" operate within the house -- in the family, in the company.

Revisions of laws

Laws of physics describe the standards by which humans predict that matter will behave. If matter behaves differently, then the laws are revised to better predict observed behavior. Clouds that fail to precipitate rain or snow as predicted will not be punished. Rather, weather scientists who fail to make reliable predictions are likely to find themselves unemployed.

Laws intended to guide human behavior are similarly subject to adjustment. A law intended to prevent drug abuse may not only fail to stem abuse, but in some way may encourage more abuse. People find ways to go around a law, or through holes in laws, or even invoke one law as justification for breaking another.

Just as laws may be toughened to "criminalize" a certain behavior, they may also be slackened to "decriminalize" the behavior. In some countries, laws concerning prostitution and pornography, alcohol and tobacco, and all manner of other such behaviors have been subject to radical change as governments take into account the effects of such behaviors on the health of individuals and families, and of society as a whole.

Penal codes are increasing being revised toward more "humanistic" treatment of offenders while also taking into consideration the "rights" of victims. Civil codes are evolving toward more liberal and egalitarian standards befitting mature democratic societies. Nationality continues to be important as a consideration of personal status, but today is less likely to be a cause for legal differentiation and social discrimination.

International private law

Private international law (���ێ��@ kokusai shihō) generally concerns individuals and non-state entities, typically in cases involving personal, family, business, and other civil matters.

A, a national of State X, wishes to divorce B, a national of State Y. And just to make things interesting, say the couple were married in State Z, which no longer exists. Which state's laws would apply if they were residing State W?

I will not attempt to answer this question -- and indeed it is probably unanswerable as stated -- but it suggests how complex an international personal matter could be.

Subnational jurisdictions

The term "international" implies relations between "states" in the sense of the member states of the United Nations. However, similar problems of applicable law may arise between between, say, residents of different states in multiple state entities such as the European Union, or in federal states like Canada, Germany, and the United States of America, among many other complex states consisting of states (by whatever name) within a state.

States within states also have multiple legal jurisdictions -- counties the state of California, for example, and municipalities within counties. There are city, county, state, and federal law enforcement agencies, and city, county, state, and federal ordinances, laws, and codes to sort out the jurisdictional and applicable law issues.

Japan as a sovereign state today has national crime and civil codes, and a national Family Register Law that reflects the family law provisions of the Civil Code. It also has 47 semi-autonomous prefectural entities, each of which has numerous municipal entities.

Yesteryear's Empire of Japan, though, at one point had six distinct legal jurisdictions. Four (Interior, Taiwan, Karafuto, Chōsen) were part of Japan's sovereign dominion, while the other two (Kwantung Province, South Sea Islands) were under Japan's legal control and jurisdiction outside its sovereign dominion.

Under Japan's 1918 Common Law, which determined applicable law in private matters within the empire, one of the jurisdictions (Karafuto) was treated on a par with the prefectural Interior, but the other two -- Taiwan and Chōsen -- were treated differently. Bureaucracies, police, and courts in these three jurisdictions operated under territorial rules, but all were parts of "Japan" when it came to the 1898 Rules of Laws, which determined applicable law in international private matters.

In other words, Japan had two laws of laws -- the 1898 law for international purposes, the 1918 law for domestic purposes. Japan consisted of only its Interior until it acquired Taiwan in 1895. Over the next two decades, it added two more territories to its sovereign empire and two territories to its legal empire, for a total of five territories outside the Interior.

"Interior" reflects "Naichi" (���n), which had been used laws and other references to Japan's prefectural entity from the early Meiji period. The five other territories were collectively called the "exterior" or "gaichi" (�O�n), but "gaichi" -- unlike "Naichi" -- was not a legal term, and in laws and most bureaucratic matter the exterior territories were referred to by their distinct names.

Law of application

Rules of application determine which laws apply to matters involving individuals or entities of different nationality or territorial status.

Each of the legal jurisdictions within the sovereign empire -- the Interior (including Karafuto), Taiwan, and Chōsen -- had their own laws. When Japan first incorporated Taiwan, Karafuto, and Korea as Chōsen into its sovereign empire, their laws were different from those of Japan's prefectural Interior, and of course also different from each other. Over the years, their laws were gradually Interiorized, while Interior laws themselves continued to evolve. Another way to put it is that the laws of all jurisdictions were works in progress as they converged toward a common legal standard.

For example, family registration laws in the three territories were governed by different family laws reflecting different customs of marriage, names, and so forth. Not only were Taiwan and Chōsen family laws gradually (and sometimes not so gradually) revised toward Interior standards, but Interior laws were modified to accommodate private matters -- such as marriage and adoption -- between individuals of different territorial statuses.

Proper law

The term proper law or governing law (�����@ junkyōhō) -- literally "standard law" [conforming to local rules] -- refers to the law that a forum court, under its own procedural laws, decides what laws or mix of laws -- local or national, domestic or foreign -- are applicable to the matter before the court.

Many contracts end with a "governing law and jurisdiction" clause. SoftBank's "My SoftBank" contract, for example, ends with the following provision concerning the disposition of disputes that might arise between SoftBank and the customer who agrees to the "use agreement [terms of use]" (���p�K�� riyō Kiyoaki) of the service, which generally is free (last revised 1 March 2011, my translation).

|

�����@�E�ٔ��NJ� �{�K��Ɋւ��鏀���@�͓��{�@�Ƃ��܂��B�܂��A�{�T�[�r�X�܂��͖{�K��Ɋ֘A���Ė{�T�[�r�X�����p�҂ƃ\�t�g�o���N�̊Ԃői�ׂ̕K�v���������ꍇ�́A�����n���ٔ�������R�̐ꑮ�I���ӊNJ��ٔ����Ƃ��܂��B Proper [Governing] law and court jurisdiction The proper [governing] law concerning this agreement shall be Japanese law. And, in the case [event] a need for litigation arises between the user of this service and SoftBank concerning this service or this agreement, the Tokyo District Court shall be the exclusive consensual [agreement] jurisdictional court of the first instance [hearing]. |

Succession

Ideally, the laws of laws of two states whose laws are candidates for application to a given matter would be constructed so as to ensure parity of treatment no matter where the matter was brought to court. For example, whether in Japan and the United States, a court would end up applying the same laws to decide whether a given divorce or will, for example, was valid.

As a legal term in inheritance law, succession (���� sōzoku) means the passing of assets upon the death of one person to another person. The main legal issue is the determination of beneficiaries -- those qualified to receive the deceased person's assets. If not specified in a will or other such instrument, the beneficiaries are usually the blood or in-law relatives stipulated by law. Since inheritance laws differ from country to country, the problem arises as to which country's laws apply upon the death of an individual who was not residing in his or own country -- among other factors that can complicate inheritance.

Japan has a law concerning the forms of valid wills -- i.e., wills that will be recognized as legal in Japan. General inheritance rules in the Civil Code apply when someone dies without leaving a will. Though increasingly people in Japan are making wills, most families rely on the default rules. Occasionally there are cases in which people who feel they deserve to be beneficiaries contest either the default rules or valid wills. For the most part, though, inheritance in Japan is a relatively simple and orderly procedure.

The inheritance rules in the Civil Code, however, automatically apply only to Japanese nationals -- i.e., members of Japanese household registers. Aliens in Japan who wish to leave their property in Japan to their families or others, whether in Japan or elsewhere, are generally advised to make a valid will in Japan, for the purpose of clarifying especially lineal and other legal relationships with beneficiaries.

A will written by a legalist at a public notary office (kōshō yakuba ���ؖ���) in Japan, for a foreign resident of Japan, must comply with Japanese law and with the foreign resident's home country law, which may defer to Japanese law. American readers note that a notary public in Japan is nothing like a notary public in most states of the United States, where dime-a-dozen licensed notaries are generally permitted only to witness signatures. A notary public in Japan is a seasoned legalist, typically a retired attorney or judge, who is thoroughly familiar with domestic law and competent to investigate laws in other countries for the purpose of writing wills that Japanese family courts will recognize as valid.

Generally -- and increasing so -- home country laws refer back to (renvoi) the law of the country where property is located. In such cases, property that an alien in Japan leaves to beneficiaries, regardless of their nationality or where they are domiciled, will be treated under Japanese law for purposes of assessing applicable inheritance taxes. Whereas Japanese law unconditionally applies to a deceased Japanese national regardless of where the decedent's property is located.

Generally, aliens who are domiciled in Japan are subject to inheritance tax on property located anywhere. Non-domiciled aliens are subject to taxes only on property located in Japan.

Such matters are governed by a number of laws in Japan, the most important of which, for purposes of international private law, are the 2007 Common Rules Law or "Common rules law concerning the application of laws" (�@�̓K�p�Ɋւ���ʑ��@ Hō no tekiyō ni kan suru tsūsokuhō) (below), and the 1964 "Law concerning proper law of forms of wills" (�⌾�̕����̏����@�Ɋւ���@�� Yuigon no hōshiki no junkyohō ni kan suru hōritsu).

The 1964 law concerning forms of wills (No. 100 of 1964, promulgated 10 June 1964, enforced from 2 August 1964) is a very short and law that centers on the following list of forms that will qualify a will as valid in Japan (based based on version as revised by the 2007 Common Rules Law, my structural translations).

|

�� �s�גn�@ �� �⌾�҂��⌾�̐������͎��S�̓������Ђ�L�������̖@ �O �⌾�҂��⌾�̐������͎��S�̓����Z����L�����n�̖@ �l �⌾�҂��⌾�̐������͎��S�̓����틏����L�����n�̖@ �� �s���Y�Ɋւ���⌾�ɂ��āA���̕s���Y�̏��ݒn�@ |

In other words, Japanese law is prepared to recognize all manner of standards of validity -- depending, of course, on the status of the decedent at time of death.

Law of personal affiliation

The concept of personal law (���l�@ zokujinhō) -- literally "affiliation personal law" -- concerns the legal status and competency of individuals as an issue in private international law (���ێ��@ kokusai shihō) -- literally "international private law". The study of both is a study of positive and negative conflict between national laws as they apply to individuals, and how such conflicts are resolved by "common laws" or "rules of laws" or "laws of laws" -- i.e., laws that determine which laws apply when more than one law might apply.

Natural and legal persons

Individuals are natural persons, while a company is a juridical (legal) persons. The nationality of a natural person is generally based on the domestic laws of the state of which the individual claims to be a national. The nationality of a juridical person is usually that of the country in which the company has been incorporated, i.e., its seat of corporation.

All manner of issues can arise between parties in international disputes. The parties might disagree as to which laws are applicable, and a court may disagree with one or both of the parties as to whether it has jurisdiction and what laws it should apply to the matter between the parties, given their status and capacity, capacity being part of status.

Dual nationality

Personal law includes a principle called "principle of personal affiliation" (���l��` zokujin shugi). This principle holds that, in at least some instances, a person should be treated according to the laws of the country with which he or she is affiliated by nationality. The nationality laws of most states have provisions for aliens to acquire the state's nationality through naturalization. In the interest of minimizing dual nationality, most states have required that naturalizing aliens lose their original nationality.

Minimizing dual nationality was justified in order to avoid conflicts of affiliation, hence conflicts of applicable law. A man who betrays a plans of a military operation will is a spy if a foreign national, but a traitor if a national. Is a dual national a spy or traitor? Laws of laws help resolve such issues.

Today, dual nationality is regarded as less of a problem because the laws of laws of most states now have fairly clear rules as to which nationality should be recognized as determining a dual national's nationality status in various situations. Generally, dual nationals are unable to simultaneously exercise the full rights of both nationalities, although they may be subject to the duties of both nationalities.

Dual US-Japanese nationals, for example, will generally be treated as US citizens in the US but as Japanese nationals in Japan. In the US they may renew their Japanese passports at Japanese consulates and otherwise avail themselves of services as Japanese nationals, but they may not seek diplomatic protection. Similarly, in Japan they may avail themselves of Citizen Services at US consulates, but in legal matters related to Japan they will be viewed as Japanese nationals.

Generally US-Japanese dual nationals will use US passports to enter and leave the US, but Japanese passports when entering or leaving Japan. Entering the US on a Japanese passport would be seen as intending to abandon US nationality, and vice versa when entering Japan on a US passport.

Multiple registration

More problematic than dual nationality is multiple registration. The United States does not have a system of family registration, nor are individuals required to establish personal registers anywhere -- notwithstanding obligations to obtain a Social Security Number.

However, every state has a voter registration law. And most states explicitly forbid voting in other jurisdictions, or at more than one place within the same jurisdiction. In other words, US citizens can exercise their rights of suffrage only if they are registered as voters -- and registration in more than one place is illegal. Moreover, registration requires that one state one's political party affiliation if any-- though one can decline to state (DS). People who move, change their name, or change their political party need to re-register.

In Japan, resident (domicile) registration rolls serve as an electoral rolls for municipal, prefectural, and national elections -- and as rolls for the legal administration of numerous other elements of municipal, national, prefectural, and municipal affiliation, from public school enrollment to national health insurance. Because registration constitutes a person's legal existence in Japan, it is against the law to be registered in more than one place as a matter of either primary register address (honsekichi), or in more than municipality as a matter of domicile address (juminhyō) if different from one's primary register address (honseki).

Aliens, whose primary affiliations (honseki) are taken to be their countries of nationality, are permitted to establish domiciles in Japan but in only one municipality. Municipal alien registration makes an alien an affiliate of both the municipality -- a village, town, city, or ward within a city -- and the prefecture that has jurisdiction over the polity.

Multiple territorial registration was also prohibited in the Empire of Japan. People in Interior, Taiwan, and Chōsen registers were equally Japanese nationals, in that they possessed the same state nationality. And they could establish a domicile in another legal jurisdiction of the empire. But they were allowed to have only one domicile. And from 1925, this domicile determined their eligibility to vote and run for office -- if they satisfied other suffrage qualifications.

Territorial (honseki) affiliations could, in some cases, change. In time, Japan introduced its Interior husband-adoption rules into Taiwan and Chōsen laws, with the result that a man in a household register in one territory could enter the register of a household in another territory as a husband. Such register migrations resulted in changes in territorial status, just as when a bride migrated to her husband's register. Child adoption also involved register migration.

Personal law in postwar Korea

The study of personal law is particularly interesting in cases of divided states -- such as when Germany divided east and west, and Korea divided north and south, after World War. Germany was a defeated state when it was occupied following invasion on different fronts by different Allied armies. But the two German states that emerged in the divided occupation zones, and claimed the same territory and inhabitants, are again a single state. Though Korea had been a state, it was not a state but part of the sovereign territory of defeated Japan when occupied by the Soviet Union in the north and the United States in the south in September 1945.

The first laws of postwar Korea were directives issued by the military governments of the USSR and the US in their respective occupation zones. The intent of the Allied Powers was to integrate the two zones under a single Korean government. But in 1948 the United States allowed the establishment of the Republic of Korea (ROK) in the north, and a month later the Soviet Union permitted the founding of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK) in the north.

Both ROK and DPRK claimed sovereignty over essentially the same "Korea" (Chōsen) and the same affiliated inhabitants -- who, under Japanese law, had been Japanese and remained Japanese until the San Francisco Peace Treaty came into force in 1952. Both states also claimed the allegiance of Koreans (Chosenese) outside Korea -- including the roughly 600,000 who had remained in "Japan" as defined by the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP) -- among the roughly 2,000,000 who were in the prefectural Interior when Japan surrendered to the Allied Powers on 2 September 1945.

"Japan" was what remained of the former Empire of Japan for Occupation purposes. At the beginning of the Occupation it consisted of the former "Interior" -- meaning the prefectures -- minus a couple of prefectures (Karafuto and Okinawa) and some small islands affiliated with other prefectures (the Kuriles, Ogasawara, et cetera). Chōsen (Korea) and Taiwan (Formosa), though still legally part of Japan, were separated from Japan for governmental and administrative purposes, to facilitate their legal cession away from Japan as "liberated" territories.

SCAP also re-defined "Japanese" to exclude Japanese who were affiliated with the separated "Outlying Areas" such as Korea and Taiwan. Under Japanese law, what SCAP called "Koreans" and "Formosans" (sometimes "Formosan-Chinese") remained "Chosenese" and "Taiwanese" -- meaning Japanese affiliated with Chōsen or Taiwan. In other words, from the start of the Allied Occupation of Japan in 1945, SCAP set in motion the alienation of Chosenese and Taiwanese from their legal status as Japanese -- before the legal separation of Chōsen and Taiwan from Japan, and consequently their loss of Japanese nationality, in 1952.

Affiliation and status

There are many layers to "affiliation" as most people have multiple affiliations. Aliens who are domiciled in Japan are affiliated with the municipality in which they have registered as aliens, and with its prefecture, but only Japanese nationals are affiliated with Japan as a state. The criminal code generally applies to everyone regardless of their status, so long as they are not protected by diplomatic immunity. Many aspects of civil law in Japan also apply equally to Japanese and aliens domiciled in Japan, but nationality determines the automatic application of some civil laws, especially in the area of family law.

"subject to the application of the Family Register Law"

Status in Japan derives from territorial affiliation, which is a matter of household registration.

Japan's Family Register Law applies only to household registers affiliated with Japan's prefectural municipalities. The present law is a postwar version of a series of family register laws going back to 1872. The Family Register law was applied to Karafuto before it formally joined the Interior, but not to Taiwan or Chōsen, which continued to be administered under their own register laws, although these laws had undergone considerable interiorization.

Phrases like "those subject to the application of the Family Register Law" (�ːЖ@�m�K�p����N���� Kosekihō no tekiyō o ukuru mono) and "those not subject to the application of the Family Register Law" (�ːЖ@�m�K�p����P�U���� Kosekihō no tekiyō o ukezaru mono) had been used in prewar laws, such as the 1927 Military Service Law, to stipulate the extent of the law's application within the empire.

The first 1943 revision of the 1927 Military Service Law extended its application to "those subject to the Family Register Law or to the provisions concerning family registers in the Chōsen Civil Matters Decree" (�ːЖ@���n���N�����ߒ��ːЃj�փX���K�胒��N����). A second 1943 revision dropped this phrase, making the law applicable to all imperial subject males of ages 20 to 40.

A supplementary provision to the 1945 revisions to the 1925 election law stipulated, which applied to all subjects, provided that, for the time being, rights of suffrage would be suspended for "those not subject to the application of the Family Register Law" (�ːЖ@�m�K�p����P�U����). Since Taiwan and Chōsen were not reached by this law, Taiwanese and Chosenese domiciled in postwar Japan were unable to vote or run for office, as they had before this revision.

Before the 1945 revision, rights of suffrage had been based on subjecthood and domicile -- i.e., subjects domiciled in election districts were eligible to vote and run for office. The 1945 revision placed territorial constraints on eligibility.

The Allied Powers had declared Koreans (Chosenese) and Formosans (Taiwanese) "liberated nationals" and the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP) had directed that they be treated as "non-Japanese" for "repatriation" purposes. "Japan" was redefined as the Interior minus a few of its territories. The Government of Imperial Japan thus lost its control and jurisdiction over all territories -- including Korea (Chōsen) and Formosa (Taiwan)-- that were outside "Japan" as downsized for occupation and reconstruction purposes.

The 1947 Alien Registration Order, enforced from the day the 1947 Constitution came into effect, provided that Chosenese and some Taiwanese would be treated as "aliens" for the purpose of the law -- while implying that were Japanese nationals. Here, too, the boundaries of status were shifted from "nationality" to "territoriality" -- in order to accommodate the treatment of people who had in effect dual statuses.

Nationality and domicile

"Affiliation" implies a having a "status" based on a formal connection with an entity, usually through registration. Most people have multiple status representing different kinds of affiliation.

One begins acquiring statuses from birth. Being legally the child of at least one's mother and also of one's father if known, constitutes a legal status. Being a male or female constitutes a legal status. One's age constitutes yet another legal status.

One then has statuses as a resident of a municipality within a larger entity, such as a county or district, which may be in a prefecture or province or state, which in turn may be part of a republic or multi-national regional entity. Among such territorial statuses, perhaps the most important is nationality.

Most states, including Japan, rely on registration of certificates of live birth to initiate determinations of legal status, including nationality. In the United States, one is not actually born in the United States as such, but in one of its states, or in the District of Columbia or a territory such as Puerto Rico. Each of these entities is governed by different birth registration laws, but require registration of birth as proof of birth within their jurisdiction.

In this sense, jus soli (right of soil) US citizenship derives through the state (or district or territory) in which a person is born. My children, born outside the United States, are both Japanese nationals and American citizens. Their Japanese nationality derives from the lineal relationship with their mother, who is a Japanese national. Their American citizenship, also based on the principle of jus sanguinis (right of blood), derives through their lineal relationship with me.

I was born in San Francisco, and so my birth certificate, filed with the city (which is also a county), serves as prima facie evidence that I am a native-born (natural) US citizen. My US passport, however, states that the United States considers me a citizen/national, and that for purposes of international law I have US nationality -- at least when I have entered a country using my U.S. passport. However, I naturalized in Japan, so I have a Japanese family register, which allowed me to obtain a Japanese passport. And my only legal status in Japan is as a Japanese national. I could have a passport of every other country in the world, but so long as I am residing in Japan on the strength of Japanese family register and Japanese passport, no other nationality would matter.

Until establishing my residence in Japan, I was domiciled in various municipalities in California, including San Francisco, Grass Valley, and Berkeley. When establishing my legal address for purposes of international law became my registered resident address in Japan. However, my "home country law" remained California -- not my country of nationality, but the state in which I had was domiciled before establishing a domicile in Japan. When naturalizing in Japan, my home country became Japan, and wherever I might be domiciled in the world as a Japanese national, my home country law would be Japanese law.

In Japan, all aliens -- except those protected by diplomatic immunity or other agreements that provide exceptional treatment under some circumstances, such as for United Nationals officials and US military personnel in Japan -- are entirely under Japan's sovereign jurisdiction. Japan is obliged to report apprehensions to an alien detainee's or arrestee's government embassy, but Japan has full jurisdiction.

Extraterritoriality

This was not the case in the late 19th century, when a number of states had extraterritorial rights in Japan and had their own consular courts. And the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP) also established extraterritorial jurisdictions and related courts in Occupied Japan in the mid 20th century. Even during the Occupation, however, only United Nations (Allied) nationals -- meaning essentially Occupation personnel -- were partly beyond the reach of Japanese courts.

During the Allied Occupation of Japan, other aliens in Japan, and many Japanese regarded as "non-Japanese" for purposes of "repatriation" and then "aliens" for purposes of alien registration, were fully subject to Japan's domestic laws and under Japan's legal jurisdiction. SCAP refused to permit Chosenese ("Koreans") in Japan -- who were "non-Japanese" and "aliens" for some legal purposes but Japanese for nationality purposes, to be treated other than in accordance with Japanese laws -- as this would have constituted extraterritoriality -- never mind that SCAP's own rules had established extraterritoriality for United Nations nationals.

Country of nationality

The so-called law of country of origin (�{���@ hongokuō) -- literally "law of [subject's] principal [own] country [of affiliation]" -- is more commonly called "law of home country" or "home country law" -- or "national law".

Metaphorically, "home country" (�{�� hongoku) seems to liken a country to a home. In law, this is generally used to mean one's country of nationality as a matter of present civil status, rather than origin as a matter of birth. Legalists also speak of the "principle of nationality" -- which, in Japanese, is commonly translated "hongokuhō shugi) (�{���@��`) -- literally "principle of home country law".

Such ideas go back to law as it was developing in Europe in the late 18th century. France's 1804 civil code included a provision which extended the reach of laws concerning status and competency to French subjects in other countries.

Home country laws generally apply in private civil matters such as marriage and inheritance.

Nationality and residential status

Nationality and residential status are two of the most fundamental attributes a national or an alien has within a given country or locality. These and other statuses -- like gender, age, mental capacity, criminal record, and a long list of other possible attributes, including in some states race or religion -- determine not only an individual's rights and duties within the country or locality, but also facilitate or limit the individual's movements within and between countries and localities.

Generally people are subject to the laws of the country in which they are transiting, traveling, sojourning, or residing -- regardless of their nationality -- i.e., regardless of whether they are nationals or aliens.

However, some laws will treat some individuals differently according to the situation and their status. In some cases diplomats are protected by immunity, in some cases not. Application of tax laws may be based on nationality and/or residency status. Traffic laws usually apply regardless of nationality or residency status. Penal codes generally do not permit someone to get away with murder simply because of their nationality or status.

National borders matter when they are crossed, as by people who have committed a crime in one country and flee to another country. Not all states have extradition agreements, but more states now cooperate in international criminal investigations. Suspects will generally be tried in the territory in which they are charged with a crime, but problems arise when someone is apprehended in one country for committing crimes in several other countries.

In the United States, the state in which a murder is committed will prosecute the case. If the suspect flees to another state, and the other state arrests the suspect for an offense committed in its jurisdiction, it will usually prosecuted its case first. Federal law enforcement agencies and federal courts will have jurisdiction, and generally priority, in cases that involve violations of Federal Codes, including some interstate offenses.

Civil matters are more likely to be subject to the laws of the territory in which they originated, or of the territory with which the parties are affiliated. Here, too, borders matter when crossed. And among the various kinds of borders, the crossing of national borders can engender problems that hinge on the nationality of the parties.

A nation's borders are demographic as well as geographic. People affiliated with a country carry its borders with them when they enter another country, possibly through birth. Nationality is not only a cause for a state to treat an alien differently from its own nationals under its own laws, but may also be a cause for treating the alien under the laws of the alien's state if not under the laws of a third state.

Nationality itself is determined by law -- and nationality laws may treat people differently according to whether they are subject to the nationality laws of another state. Under Japanese law, for example, any person who is born in Japan, who does not qualify for Japanese nationality, will be treated as an alien whose nationality is determined by the laws of one or more other states.

Qualifications for Japanese nationality include instances in which both of the child's parents are stateless -- that is, the child is beyond the reach of another state's nationality law. If one of the child's parent's is a non-stateless alien, then Japanese law expects that the child will gain the nationality of that parent's nationality. If the child does gain that nationality, then the child becomes an alien in Japan with that nationality. If for some reason the child cannot obtain the nationality of the non-stateless alien parent, the child will be stateless -- and will be treated as a stateless alien under Japanese law. A child who gains the nationality of both alien parents who are of different nationalities will be treated as a national of only one of those states while in Japan -- most likely the most recently acquired nationality. A Japanese who has the nationality of another state will be treated as only Japanese.

If two Republic of Korea nationals in Japan have a child, the nationality of the child is a matter of ROK nationality law, to be determined by the ROK government or its legal representatives in Japan. Japan has no say in how ROK's nationality law operates anywhere in the world.

If a Japanese national and an ROK national have a child, Japanese law will also apply -- if the Japanese parent registers the child in a timely manner in his or her family register. If the parents are not married, the father has to recognize the child in a timely matter. Until 1985 in Japan's law, and until 2000 in ROK's law, whether the parents were married also mattered.

Place of domicile

Domicile is a legal term for the address where a person is presumed to intend to reside on a continuing basis -- not necessarily permanently, and not necessarily habitually -- but principally. In Japanese law, "domicile" (�Z�� jūsho) is usually taken to mean the address at which a person is registered as a resident -- in Japan or outside Japan.

Japanese who are registered as a resident of a Japanese municipality are considered domiciled in the municipality. Japanese who have never registered as a resident in Japan, or have declared themselves a resident of another country or otherwise abandoned their municipal resident registration status in Japan, are not regarded as domiciled in Japan.

Aliens with statuses of residence of 90 days or longer are also obliged to register as residents of the municipality in which they live. Aliens with longer term statuses, including of course aliens permitted to permanently reside in Japan, are considered to be domiciled in Japan for purposes of applying Japanese law.

Note that, in Japanese law, "domicile" is the more conventional term for an address based established by registration of one's residence. As such is is most likely found in Japan's domestic laws, whereas "habitual address" (see below) is more likely found in Japanese laws that reflect recent trends in international conventions concerning conflicts of laws.

Place of habitual residence

Habitual residence is the place where a person habitually resides. In considerations of applicable law, a person can have only one such residence -- but the determination of this residence may be difficult if the person has a number of residences.

Japanese, by definition, have a "honseki" or "principal register" address. But this is merely the address of the municipal register that territorially affiliates them with Japan's sovereign dominion, and thereby makes them part of Japan's nation. They may never have lived at, or even been to, this address.

Japanese who legally reside in Japan have an address based on their resident registration in a Japanese municipality, which is often other than the address of their principal register.

Japanese who legally reside outside Japan have a principal register address in Japan but no resident registration address. Such Japanese have either been born outside Japan and never established a resident registration address in Japan, or at one time they had such an address in Japan but filed a notification in Japan, or at a Japanese consulate, to the effect that they had established a domicile outside Japan.

An habitual address, however, is where the person has actually been residing, in the eyes of the court, apart from their domicile address. A Japanese with a legal domicile in Japan or even outside Japan, who begins living somewhere else in Japan or outside Japan without registering in the different locality, may be considered to be habitually residing in the different locating, which will then be taken as the habitual address for purposes of determining applicable law.

"Habitual address" is therefore more flexible than "domicile" address.

Note that "habitual" does not mean "permanent". Aliens in Japan who have a "permanent" status of residence are considered "domiciled" in Japan -- but many aliens with non-permanent statuses of residence are also "domiciled" in Japan for legal purposes. Japanese, however, are never considered "permanent" residents of Japan -- but only "domiciled" and/or "habitual" residents.

An alien who has a domicile in Japan may also be considered as having an "habitual address" elsewhere in Japan. In some circumstances, an alien who is domiciled outside Japan may also be regarded as habitually residing in Japan. Such distinctions are made to give courts flexibility in determining applicable law in cases involving complex residential behaviors -- such as someone is registered in one municipality but actually lives in another, or someone who is not domiciled in Japan but spends significant parts of their life in Japan.

Sometimes "intention" is taken as the criterion for establishing "habitual residence". In other words, establishing a principal home at a particular address may be taken as intention to habitually reside and be domiciled at that address -- even though the person may have several homes, and be moving around for business or other purposes.

Status and capacity

The status of the parties will determine whether they have the capacity to conclude a binding agreement such as an alliance of marriage or a business contract, or write a will that is recognized as valid. A natural person's status is usually based on nationality, domicile, or habitual residence, while the status of a legal person such as a company is generally based on where the company incorporated (equivalent to nationality) or later established an operation (equivalent to domicile).

Status

The term status (�g�� mibun) in especially important in Japanese law, including the 1947 Constitution. The term is most commonly used in connection with one's status in a family register, including one's relationship to persons who qualify as blood (lineal) or in-law relatives.

Family registers are primary records of status acts (�g���s�� mibun kōi) and resulting statuses -- most essentially birth, death, marriage, divorce, adoption alliances and dissolutions, but also (today) change of gender. Resident registers for Japanese, and alien registers for foreigners permitted to reside in Japan, establish one's domicile for purposes of municipal and prefectural affiliation and related rights and duties under national, prefectural, and municipal laws. Alien registers today include information concerning family ties to others in Japan, whether Japanese or aliens. There are plans to integrate Japanese and alien resident registers for the purpose of improving the administration of all matters that derive from municipal registration.

Change of nationality -- from one nationality to another, including acquisition or loss of Japanese nationality -- also constitute status acts. Japanese who renounce their nationality in Japan will be removed from their Japanese register and enrolled in an alien register. Aliens who are permitted to naturalize will be enrolled in a Japanese register in lieu of alien registration.

Of interest here, though, are mainly status acts which effect the formal definition of family relationships -- such as spousal or parent-child statuses.

Capacity

The term capacity, referring to the ability to perform a legal act, is an aspect of status. Age, and being married, are statuses, as is national or local affiliation. A natural person has to have reached a certain age before being subject to compulsory education laws and qualifying for enrollment in public schools. Age also figures in capacity to marry, vote, run for office, qualify for national pension benefits, or for health care benefits as an elderly person. A married person does not have the capacity to marry another person. And, under present law, a child who has not been legitimated by the marriage of its parents has an inferior status to a legitimate child when it comes of inheritance.

An alliance of marriage between two parties in Japan can be registered if both parties have the capacity to marry under the laws of their respective states of nationality. If both are Japanese, then of course only Japan's laws apply, and the capacity of the parties will be determined by their family register statuses, which reflect their ages, genders, and marital statuses. Registrations of marriages involving an alien or aliens generally require evidence of recognition of the marriage by the consulate(s) of the concerned foreign state(s).Capacity may also be limited by a certified physical or mental condition, or by a past violation of some kind, among other aspects of status. Capacity may also be based on whether or not a person has acquired valid licenses or permits.

In the Empire of Japan, register status including gender -- but not race or ethnicity, which were not matters of law and had no legal significance -- determined migrations between Interior, Taiwan, and Chōsen registers and corresponding changes in territorial status (affiliation). Interior women became Taiwanese or Chosenese when marrying a Taiwanese or Chosenese, and Taiwanese or Chosenese men adopted as sons or husbands into an Interior household became Interiorites.

These territorial statuses determined who lost and kept their Japanese nationality in 1952 when Taiwan and Chōsen were fully separated from Japan's national sovereignty.

As males generally had superior status to women in family matters in all three entities, the affiliation of the groom generally determined applicable law in interterritorial marriages. Generally the woman changed her territorial status.

Under the nationality laws of many states at the time, including Japan and for a while the United States, a woman who married a man of a different nationality stood to lose her natal nationality if she gained her husband's nationality through marriage. In other words, the gender-driven reciprocity of territorial laws within Japan was a fairly universal standard.

Japan's first de facto nationality law was the 1873 proclamation providing rules for an alien woman and in some cases an alien man to Japanese through marriage to a Japanese, and for a Japanese women to lose her status as Japanese if through a marriage to a foreign man she gained his status. Such provisions were embraced by the 1899 Nationality Law, which generally reflected the standards of family law in Japan while also comporting with the nationality laws of most other countries.

Capacity and "cultural defense"

"Capacity" includes mental capacity. Children generally do not have the legal capacity to decide legal matters for themselves, hence a parent or guardian makes decisions on their behalf. Between the black and white of minor and adult status are gray zones in which a minor may legally act with parental approval.

Young offenders are usually treated differently than adult offenders. And people who commit an offense under the influence of alcohol or drugs, or cause an accident in the midst of a heart attack or epileptic seizure, may also be regarded as having less "capacity" at the time of the offense or accident.

Is "culture" also an aspect of "capacity"? I.e., should "culture" be viewed as qualifying one's personal "capacity" to commit an offense?

I have long been interested in attempts in some courts, particularly in the United States but also elsewhere, to argue what is commonly called a "cultural defense". In a word, a "cultural defense" is an attempt to dismiss or mitigate charges on the grounds that, though an act violated applicable laws in the jurisdiction where it was committed, it was not against the law, or was a lesser order of offense, in the defendant's home country.

Such pleas have generally failed -- because the powers that cultural determinists attribute to "culture" are generally not cultural but personal. I.e., the acts attributed to "culture" are generally viewed as problematic individual acts even in the country whose "culture" is alleged to have been a contributing if not precipitating factor.

For a look at a California case in which a cultural defense was rejected, see The Trial of Fumiko Kimura.

Japan's laws of laws

Rules for determining applicable laws

among conflicting territorial laws

Japan has had a number of laws for determining applicable laws, as well as provisions in laws which stimulate rules of applicability. A number of early Meiji laws included applicability rules. The first law of laws as such, the 1890 Rules of Laws (�@�� Hōrei) [Law No. 97], was intended to work together with the 1890 Civil Code (���@ Minpō) [Law No. 98]. The Civil Code, though promulgated, never came into effect.

The 1890 Rules of Laws was abrogated upon the promulgation of an entirely new version in 1898 (Law No. 10), in conjunction with the promulgation of the second part of a new Civil Code (Law No. 9), and it was enforced together with the new Civil Code (the first part of which had been promulgated in 1896 as Law No. 89).

The 1890 Civil Code included articles that were intended to serve as rules which would satisfy Article 18 of the 1890 Constitution, which provided that qualifications being a "subject of Japan" (���{�b�� Nihon shinmin) would be determined by law.

The 1890 Rules of Laws used the term "law of country of origin" [home country law] (�{���@ hongoku hō) as well as "law of [place of] domicile" (�Z���̖@�� jūsho no hōritsu) and "law of [place of] residence" (�����̖@�� kyosho no hōritsu). By no later than the 1948 revision of the 1898 Rules of Laws, the latter two phrases has become "law of place of domicile" (�Z���n�@ jūshochi hō) and "law of place of residence" (�����n�@ kyoshochi hō). From the 1990 revision, the later of these two classifications of address became "law of place of habitual residence" (�틏���n�@ Jō-kyoshochi hō), by then the more familiar expression in international law.

The 1898 Rules of Laws, which was intended to resolve conflicts in private law both within the Empire of Japan and between the empire and other state entities, was last revised from 2000. The entire law was revised and replaced by the present 2007 law, called Common Rules Law concerning application of laws -- or, more commonly in English, "General law concerning application of laws".

The 1890 Rules of Law made no reference to the Interior, or to Okinawa or Hokkaidō as prefectures within the Interior to be treated somewhat differently with respect to determining enforcement. And of course it made no reference to Taiwan, which was not part of Japan until 1895.

The 1898 law, however, covered Taiwan, Hokkaido, Okinawa, and a few other island territories that were somewhat exceptionalized with regard to how the government could determine effectuation dates of statutes. The law was not intended to address the sort of "law of laws" issues that arose in private matters between subjects affiliated with different legal jurisdictions of the Empire of Japan -- meaning, in 1898, the Interior (including Hokkaido and Okinawa) and Taiwan.

Japan's legal territories included entities that were part of its sovereign dominion (Interior, Taiwan, Karafuto, and Chōsen), and entities that not part of its sovereign dominion (Kwantung Province and South Sea Islands). From 1918, Japan began to enforce the so-called Common Law -- a law that determined which jurisdiction's laws would apply in matters involving more than one jurisdiction.

1890 Rules of Laws

6 October 1890

Promulgated 6 October 1890 (Law No. 97)

This first Rules of Law as such was promulgated in conjunction with the promulgation of the 1890 Civil Code (Law No. 98) in mind, but this Civil Code was never enforced.

The importance of both 1890 laws, from the point of view of nationality law in Japan, is the manner in which they continued to regard the "standings" [statuses] of "Japanese" and "aliens" as "national standings" -- called "nationality" in the 1899 Nationality Law. See particulars in the immediately preceding section (above), and following Article 8 of this law (below).

|

1890 Rules of Laws (Law No. 97) |

|

Japanese textThe Japanese text is adapted from a copy posted at the "International private law room" (���ێ��@�̕���) of a personal website created by Nakanishi Yasushi (�����N), a professor of international private law at Kyoto University Law School (���s��w��w�@�@�w������). Nakanishi is listed as one of the translators of one of the received translations of the 2007 Common Rules of Law (see below). I have shown the posted version as received -- with present-day kanji, hiragana rather than katakana, and voicing and punctuation. As received, the posted version lacks the first two articles, and I have not been able to vet its text against contemporary printed copies. Structural English translationThe structural English translations of selected articles are mine. CommentaryWords selected for commentary have been highlighted in bold blue in both the Japanese text and the English translations. |

|

| �@�� | Rules of Laws |

|

��3�� �l���g���y���\���͑��{���@�ɏ]�ӁB �e���̊W�y�ё��W��萶���錠���`���ɕt�Ă��������B |

Article 3 The status and capacity of a person shall be in accordance with [the person's] home country law. Regarding also the rights and duties that engender [arise] from [pursuant to] relationships of kin [family relatives] or their relationships, they shall be the same [in accordance with the person's home country law]. |

Status and capacity"Status" (�g�� mibun) and "capacity" (�\�� nōryoku) have been among the most important terms in law. They are especially important in Japanese family law, hence Paragraph 2 of Article 3, stipulating that the determination of a person's status and capacity would be based on the person's home country law, also in family matters. |

|

|

��4�� ���Y�s���Y�͑����ݒn�̖@���ɏ]�ӁB�R��ǂ������y�ш②�ɕt�Ă͔푊���l�y�ш②�҂̖{���@�ɏ]�ӁB |

Article 4 |

|

��5�� �O���ɉ��Ĉׂ����鍇�ӂɕt�Ă͓����҂̖������َ͖��̈ӎv�ɏ]�Ђĉ���̍��̖@����K�p��������ށB �����҂̈ӎv�����Ȃ炴��ꍇ�ɉ��Ă͓����l�Ȃ�Ƃ��͑��{���@��K�p���������l�ɔ�炴��Ƃ��͎����㍇�ӂɍő�̊W��L����n�̖@����K�p���B |

Article 5 |

|

dōkoku-jin (�����l) or "person of the same country" is used reference to someone who is affiliated with the country in which movable or immovable property is located. |

|

|

��6�� �O���l�����{�ɉ��ē��{�l�ƍ��ӂ��ׂ��Ƃ��͊O���l�̔\�͂ɕt�Ă͑��{���@�Ɠ��{�@�Ƃ̒��ɂč��ӂ̐����ɍł��L�v�Ȃ�@����K�p���B |

Article 6 When an alien effects in Japan an agreement with a Japanese, regarding the capacity of the alien, among [the alien's] home country law and Japanese law, [the parties] shall apply the most most beneficial law to the formation of the agreement. |

|

��7�� �s���̗����s���̑��Q�y�і@����̊Ǘ��͑������̐�������n�̖@���ɏ]�ӁB |

Article 7 |

|

��8�� �{���@��K�p�������ʂ̏ꍇ�ɉ��ĉ���̍������������L������Җ��͒n���Ɉ˂�@�����قɂ��鍑�̐l���͑��Z���̖@���ɏ]�ӁB�Ⴕ�Z���m�ꂴ��Ƃ��͑������̖@���ɏ]�ӁB ���{�l�ƊO���l�̕�����L����҂͓��{�@���ɏ]�Ж���ȏ�̊O������������L����҂͍Ō�ɔV���擾�����鍑�̖@���ɏ]�ӁB |

Article 8 In various cases [instances] in which the home country law is to apply, those [persons] who possess a national status and the people of a country in which laws differ according to region shall follow the law of their domicile. When the domicile is not known [they] shall follow the law of [their] residence. Those who possess the statuses of [both] a Japanese and an alien shall follow Japanese laws, and those who possess two or more foreign national statuses shall follow the laws of the country [of the status] most lately [recently] acquired. |

Dual nationality recognized in 1890Paragraph 2 of Article 8 of the 1890 Rules of Laws recognized the legal fact that some Japanese possess more than one nationality -- referred to then as "bungen" (����) meaning "standing" or "status". The 1898 Rules of Laws (see below) referred to "nationality" as (kokuseki ����), a newer word now universally accepted as the term signifying legal belonging to a state. The point, though, is that -- since the Meiji period -- Japan's domestic laws have recognized the existence of multiple nationality among Japanese. Having more than one nationality has never, per se, been illegal -- which does not mean that Japan accepts it. In fact, most states -- even those that don't object to multiple nationality -- restrict multiple nationals to one nationality through stipulations in laws of laws like Article 8 in Japan's 1890 Rules of Laws. National standing and multiple statusesThe importance of this article, in the 1890 Rules of Laws, is that it clearly recognizes the event of a person having multiple national statuses, including those of a Japanese and an alien. However, only one status could be recognized, and in the event that a person qualified as both a Japanese and an alien, the person would be treated as Japanese, and hence Japanese law would apply. kokumin bungen (��������) refers to a person's "national standing". The term "kokuseki" had not yet come into use. bungen (����) or "standing" [status] was the term used in the 1873 proclamation which provided for changes of family register status in alliances of marriage and adoption between Japanese and aliens. kokumin (���� kokumin) or "national" referred to a person as an "affiliate" (�� min) of the "nation" [country, state] (�� koku). jinmin (�l��) or "person" is used to refer to a person as a demographic affiliate of a country. Just as kokumin was used to refer to individuals as "nationals" or to the population of individuals as a "nation", jinmin was also used to collectively refer to "the people" of a nation. "national standing""Japanese" (���{�l Nihonjin) and "alien" (�O���l gaikokujin) are "standings" [statuses] (���� bungen) which are "possessed" (�L���� yū). Similarly, "foreign national standing" (�O���������� gaikoku kokumin bungen) in possessed. The 1890 Rules of Laws dovetailed with the 1890 Civil Code, which used the terms "national standing [status]", "standing [status] of Japanese" (���{�l�̕��� Nihonjin no bungen), and "standing [status] of alien" (�O���l�̕��� gaikokujin no bungen) in the articles that were intended to serve as a law of nationality. This version of the Civil Code, though promulgated, was never enforced. The 1890 Civil Code and Rules of Laws adopted this usage in conformity with previous standards of usage, despite reference in the 1890 Constitution to "subjects" (�b�� shinmin). The status provisions in the 1890 Civil Code were intended to satisfy the requirement of Article 18 in the 1890 Constitution, to the effect that the qualifications to be a subject of Japan would be determined by law. See 1873 intermarriage proclamation and 1890 Civil Code for full details. |

|

|

��9�� �����؏��y�ю����؏��̕����͔V����鍑�̖@���ɏ]�ӁB�A��l���͓����l�Ȃ鐔�l�̍�鎄���؏��ɕt�Ă͑��{���@�ɏ]�ӂ��ƂB |

Article 9 |

|

��10�� �v���̍��Ӗ��͍s�ׂ�嫂��V���ׂ����̕����ɏ]�ӂƂ��͕�����L���Ƃ��A�̈ӂ��Ȃē��{�@����E������Ƃ��͑����ɍ݂炸�B |

Article 10 |

|

��11�� �O���ɉ��đ����̕����Ɉ˂�č�肽��؏��͕s���Y�������ړ]����s�ׂɌW��Ƃ��͑��s���Y���ݒn�̒n���ٔ��������͑��̍s�ׂɌW��Ƃ��͓����҂̏Z�����͋����̒n���ٔ������؏��̓K�@�Ȃ邱�Ƃ����F�������ɔ�Γ��{�ɉ��đ����p��v�����ނ邱�Ƃ��B |

Article 11 |

|

��12�� ��O�҂̗��v�ׂ̈߂ɐݒ肷������̕����͕s���Y�ɌW��Ƃ��͑����ݒn�̖@�����̏ꍇ�ɉ��Ă͑������̐������鍑�̖@���ɏ]�ӁB |

Article 12 |

|

��13�� �i�葱�͑����s���ׂ����̖@���ɏ]�ӁB�ٔ��y�э��ӂ̎��s���@�͑����s���ׂ����̖@���ɏ]�ӁB |

Article 13 |

|

��14�� �Y���@�������@�̎����Ɋւ��y�ь��̒������͑P�ǂ̕����Ɋւ���Ƃ��͍s�ׂ̒n�����҂̍��������y�э��Y�̐����̔@�����͂����{�@����K�p���B |

Article 14 |

|

��15�� ���̒������͑P�ǂ̕����Ɋւ���@����ఐG�����͑��K�p��Ƃ����Ƃ��鍇�Ӗ��͍s�ׂ͕s�����Ƃ��B |

Article 15 |

|

��16�� �@�g���y�є\�͂��K�肷��@����Ƃ���鍇�Ӗ��͍s�ׂ͖����Ƃ��B |

Article 16 |

|

��17�� �����͖@���ɕs���s�����͌��_����������Ƃ��čٔ����ׂ������₷�邱�Ƃ��B |

Article 17 |

1898 Rules of Laws

16 July 1898

Promulgated 21 June 1898 (Law No. 10)

Enforced from 16 July 1898 concomitant with the 1898 Civil Code

Effective through 31 December 2006

Replaced from 1 January 2007 by the Lost effectiveness from 1 January 2007 by Common Rules Law concerning the application of laws (see below).

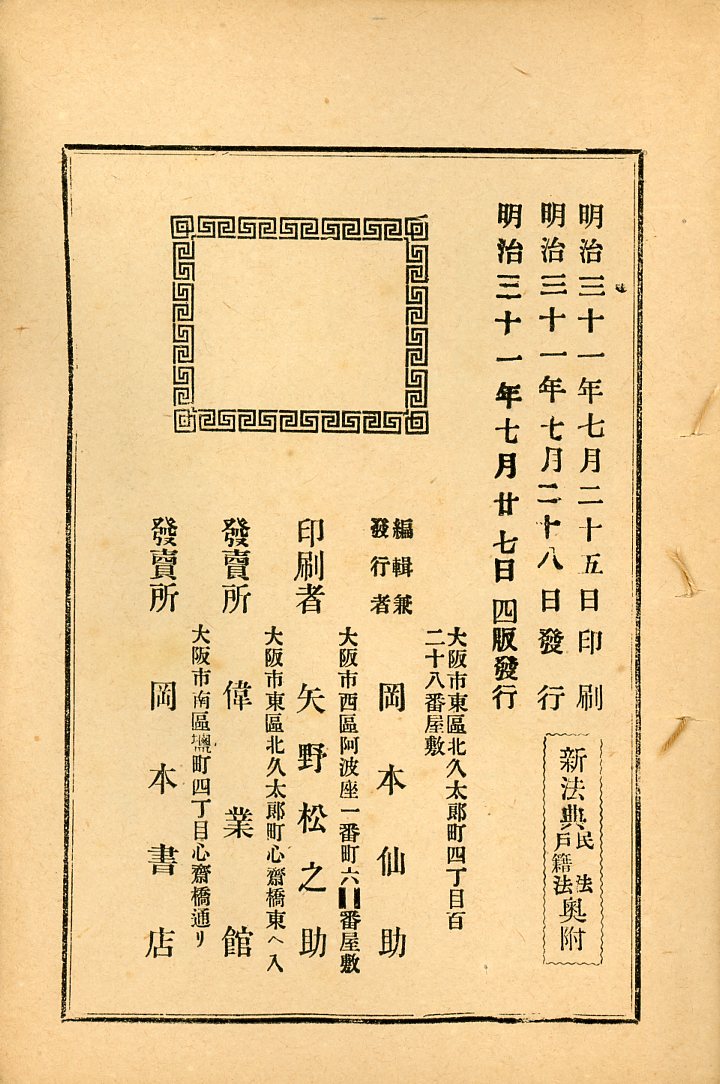

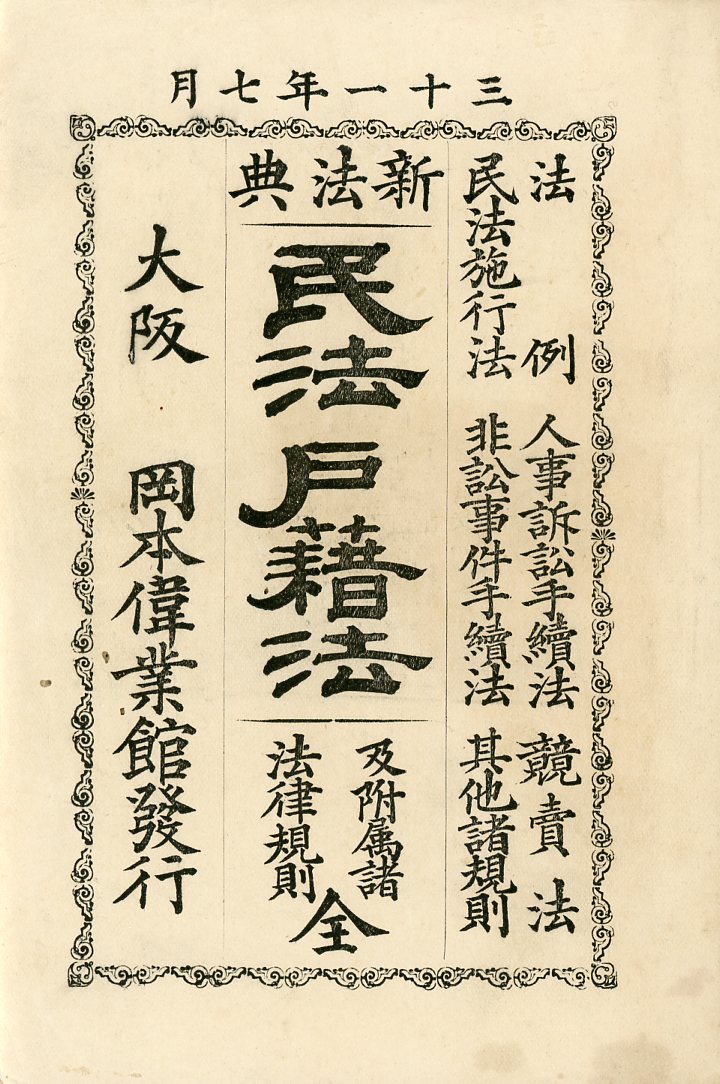

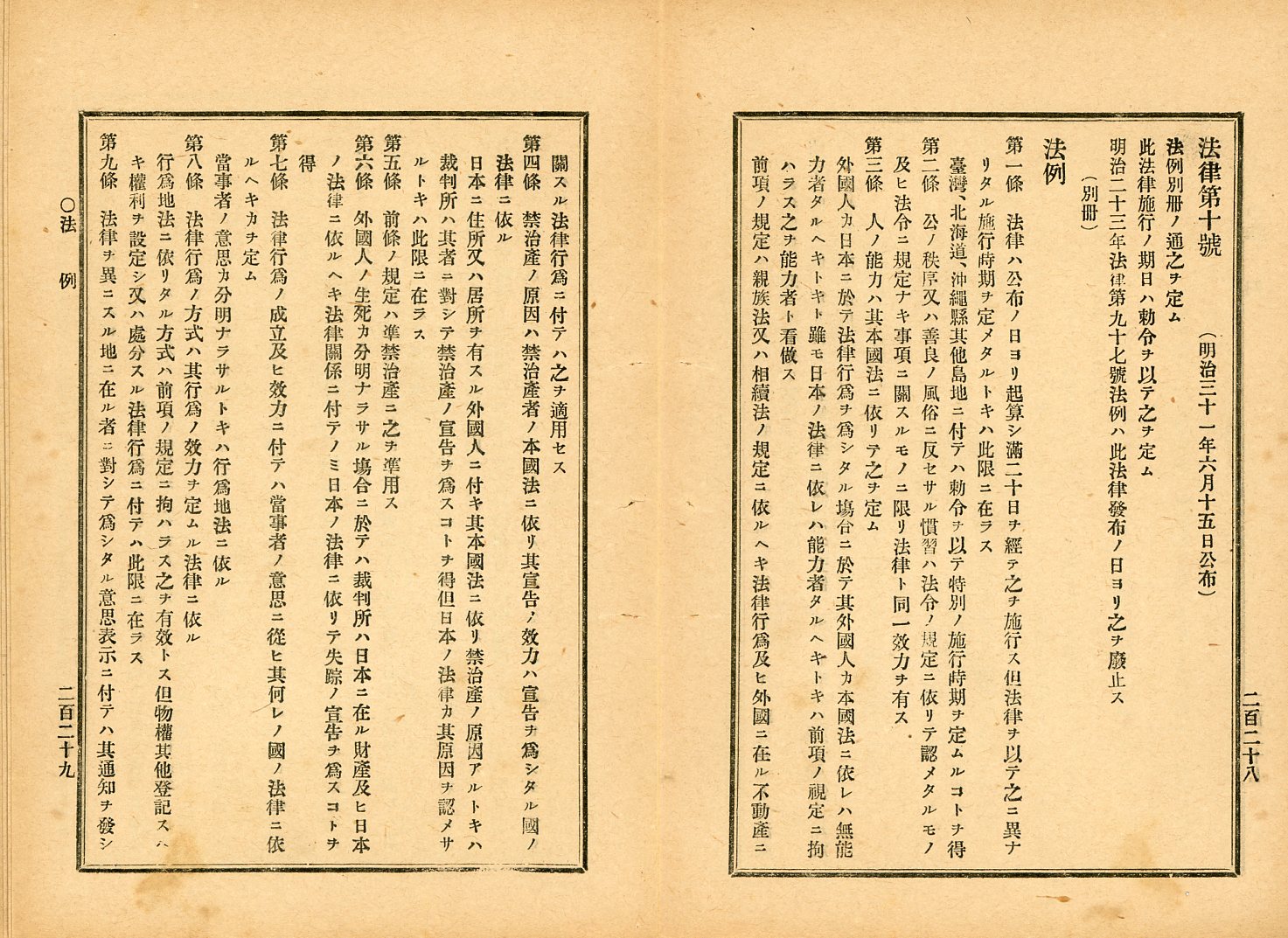

The sanctioning and promulgation particulars are as follows (my translations).

|

1898 Rules of Laws (Law No. 10) |

|||||||

Japanese textThe Japanese text of "Rules of Laws" (Hōrei �@��) as promulgated in 1898 has been vetted against the text of law published by Okamoto Sensuke in Ōsaka immediately after the law was promulgated and enforced in 1898 (see images to the right). I have replaced missing older forms of graphs with their present-day forms in what otherwise appears to be a contemporary text. Structural English translationThe structural English translations of selected articles are mine. CommentaryWords selected for commentary have been highlighted in bold blue in both the Japanese text and the English translations. Other than Article 1, concerning enforcement, I have translated and commented only on articles related to family matters including marriage, children, and inheritance (Articles 13-26), nationality and region, residence versus domicile, and renvoi (when home country law refers back to law of locality) (Articles 27-29), and what happens when an applicable foreign law contravenes notions of public order and decency in Japan (Article 30). Laws of lawsJapan's 1898 "Rules of Laws" was a "laws of laws" -- a law that governs how laws of Japan and other countries were to be applied within Japan. The purpose of such laws is to resolve "conflicts of law" that would arise in a case in which two or more competing laws might apply, such as when a man and woman of different nationalities marry or divorce, whether in the country of the man or of the woman, or in a third country. Most cases that require determinations of applicable law are about "private matters" -- meaning matters concerning individuals in the course of their relationships with other individuals, especially family relationships, including inheritance -- but also matters concerning property, such as real estate and other assets. Determinations of court jurisdictions also fall under the concern of "laws of laws" or laws that resolve "conflict of laws". Determining court jurisdiction and applicable law, however, are different matters, as when a court in one country may be obliged to deal with a case but under the laws of another country. Home country lawLaws of laws are typically invoked in cases that involve persons who belong to a country other than the country in which they are living, and property that is owned by a person who is not living in, and/or does not belong to, the country where the property is located. "Home country" (hongoku �{��) generally refers to "the country one belongs to" (zoku suru kuni �����鍑) as a subject, national, or citizen -- i.e., "the country in which one possesses nationality" (kokuseki o motsu kuni ���Ђ�����). And "home country law" (hongoku-hō �{���@) refers to the laws of that country. RegionalityFor practically all Japanese living in Japan, family matters involve only other Japanese, and property matters involve only assets in Japan. And because Japan's national laws are shared by all provinces and municipalities in Japan -- unlike the United States, where semi-sovereign states have their own penal and civil codes, property laws and sundry licensing systems, and courts. Conflicts arise between the states, and between the states and the federal government, which has its own body of laws, law enforcement agencies, and courts. While today Japan's sovereign dominion consists of a single legal territory, with nationally uniform laws and courts and nationally overseen local police, in the past it had 4 distinct legal territories within its own sovereign dominion -- the prefectural Interior, Taiwan, Karafuto, and Chōsen -- which came with their own laws and bureaucratic practices. And so Imperial Japan required a domestic laws of laws to determine applicable law in private matters between Japanese -- Interiorites, Chosenese, Taiwanese, and Karafutoans -- belonging to different legal territories. See 1918 Common Law for details. |

|||||||

|

���隠�c���m���Ӄ��S�^���@�გ�ىV䢃j�V�����z�Z�V��

|

I [the emperor] sanction the Rules of Laws which has passed the approval of the Imperial Diet and herein promulgate it.

|

||||||

|

�@����\�j �@��ʙe�m�ʔV���胀 ���@���{�s�m�����n���߃��ȃe�V���胀 ������\�O�N�@�����\���j�@��n���@��ᢕz�m�������V���E�~�X �ʙe |

Law No. 10 The Rules of Laws, as per separate volume [supplement], shall be established. The date of enforcement of this law shall be determined by an imperial ordinance. Law No. 97 of Meiji 23 [1890] shall be abrogated from the day of the promulgation of this law. Supplement |

||||||

| �@�� | Rules of Laws | ||||||

| Japanese text | Structural translation | ||||||

|

��꞊ �@���n���z�m�������N�Z�V�ޓ�\�����S�e�V���{�s�X�A�@�����ȃe�V�j�كi���^���{�s�������胁�^���g�L�n�����j�݃��X �i�s�A�k�C���A����p�������n�j�t�e�n���߃��ȃe���ʃm�{�s�������胀���R�g���� |

Article 1 As for a [statute] law, [the government] shall enforce it [when] a full twenty days have passed computed from the day of [its] promulgation; provided, however, that this shall not apply when [the government] determines by law an enforcement date different from this. Regarding Taiwan, Hokkaidō, Okinawa prefecture, and [certain] other insular lands [places], it shall be possible for [the government] to determine a special [specific] enforcement date by imperial ordinance. |

||||||

Taiwan, Hokkaido, Okinawa prefectureHokkaido, Okinawa, and the other insular territories referred to in Paragraph 2 of Article 1 were parts of the Interior. Taiwan became an external part of Japan's sovereign territory in 1895, under the terms of the Treaty of Shimonoseki between Japan and China following the Sino-Japanese war of 1894-1895. See Taiwan, Hokkaido, Okinawa prefecture, et cetera below for further details. |

|||||||

|

��� ���m�������n�P�ǃm�����j���Z�T�����K�n�@�߃m�K��j�˃��e�F���^�����m�y�q�@�߃j�K��i�L�����j萃X�����m�j�����@���g����m���̓��L�X |

Article 2 |

||||||

|

��O�� �l�m�\�̓n���{���@�j�˃��e�V���胀 �O���l�J���{�j���e�@���sਃ�ਃV�^���ꍇ�j���e���O���l�J�{���@�j�˃��n���\�͎҃^���w�L�g�L�g嫃����{�m�@���j�˃��n�\�͎҃^���w�L�g�L�n�O���m�K��j�S�n���X�V���\�͎҃g�Ř�X �O���m�K��n�e���@���n��㔖@�m�K��j�˃��w�L�@���sy�q�O���j�݃��s���Y�j萃X���@���sਃj�t�e�n�V���K�p�Z�X |

Article 3 |

||||||

|

��l�� �֎��Y�m�����n�֎��Y�҃m�{���@�j�˃����鍐�m���̓n�鍐��ਃV�^�����m�@���j�˃� [2] ���{�j�Z�����n�������L�X���O���l�j�t�L���{���@�j�˃��֎��Y�m�����A���g�L�n�ٔ����n���҃j���V�e�֎��Y�m�鍐��ਃX�R�g�����A���{�m�@���J���������F���T���g�L�n�����j�݃��X |

Article 4 |

||||||

|

��ܞ� �O���m�K��n���֎��Y�j�V�����p�X |

Article 5 |

||||||

|

��Z�� �O���l�m�����J�����i���T���ꍇ�j���e�n�ٔ����n���{�j�݃����Y�y�q���{�m�@���j�˃��w�L�@��萌W�j�t�e�m�~���{�m�@���j�˃��e���H�m�鍐��ਃX�R�g���� |

Article 6 |

||||||

|

�掵�� �@���sਃm�����y�q���̓j�t�e�n�c���҃m�ӎv�j�n�q�������m���m�@���j�˃��w�L�J���胀 �c���҃m�ӎv�J�����i���T���g�L�n�sn�@�j�˃� |

Article 7 |

||||||

|

�攪�� �@���sਃm�����n���sਃm���̓��胀���@���j�˃� �sn�@�j�˃��^�������n�O���m�K��j�S�n���X�V���L���g�X�A���ܑ����o�L�X�w�L�ܗ����ݒ�V���n�|���X���@���sਃj�t�e�n�����j�݃��X |

Article 8 |

||||||

|

��㞊 �@�����كj�X���n�j�݃��҃j���V�eਃV�^���ӎv�\���j�t�e�n���ʒm��ᢃV�^���n���sn�g�Ř�X �_��m�����y�q���̓j�t�e�n�\���m�ʒm��ᢃV�^���n���sn�g�Ř�X��V���\������P�^���҃J������ਃV�^���c���\���mᢐM�n���m���T���V�g�L�n�\���҃m�Z���n���sn�g�Ř�X |

Article 9 |

||||||

|

��\�� ���Y�y�q�s���Y�j萃X�����ܑ����o�L�X�w�L�ܗ��n���ړI���m���ݒn�@�j�˃� �O���j�f�P�^���ܗ��m���r�n�������^�������m�����V�^���c���j���P���ړI���m���ݒn�@�j�˃� |

Article 10 |

||||||

|

��\�꞊ �����Ǘ��A�s�c�������n�s�@�sਃj�����e���X���܃m�����y�q���̓n�������^�������mᢐ��V�^���n�m�@���j�˃� �O���m�K��n�s�@�sਃj�t�e�n�O���j���eᢐ��V�^�������J���{�m�@���j�˃��n�s�@�i���T���g�L�n�V���K�p�Z�X �O���j���eᢐ��V�^�������J���{�m�@���j�˃��e�s�@�i���g�L�g嫃���Q�҃n���{�m�@���J�F���^�����Q���������m�|���j��T���n�V�������X���R�g�����X |

Article 11 |

||||||

|

��\�� ��樓n�m��O�҃j���X�����̓n���҃m�Z���n�@�j�˃� |

Article 12 |

||||||

|

��\�O�� ���������m�v���n�e�c���҃j�t�L���{���@�j�˃��V���胀�A�������n�������s�n�m�@���j�˃� �O���m�K��n���@�掵�S���\�����m�K�p���W�P�X |

Article 13 The requisites for the formation of a marriage, for each of the concerned persons (parties), shall be in accordance with their home country laws. However, its formalities shall be in accordance with the locality where the marriage takes place. The provision (stipulation) of the preceding paragraph shall not impede the application of Article 777 of the [1898] Civil Code [Article 741 of 1948 Civil Code]. |

||||||

Article 777 of [1898] Civil CodeArticle 777 of the 1898 Civil Code (Article 741 of the 1948 Civil Code) stipulated as follows (my translation). When desiring to effect a marriage between Japanese in a foreign country, the resident legation or consul of Japan in the country shall, in the case of effecting its notification, similarly apply (mutatis mutandis) the provisions (stipulations) of the preceding 2 articles [Articles 775-776 of the 1898 Civil Code, Articles 739-740 of 1948 Civil Code]. Articles 775-776 (739-740) concern family register actions to be taken when effecting a marriage in Japan. | |||||||

|

��\�l�� �����m���̓n�v�m�{���@�j�˃� �O���l�J���ˎ�g���v������ਃV���n���{�l�m���{�q�gਃ��^���ꍇ�j���e�n�����m�w�̓n���{�m�@���j�˃� |

Article 14 The effectiveness of a marriage shall be in accordance with the home country law of the husband. In a case in which a foreigner effects a marriage with a female head of household, or becomes an adopted son-in-law of a Japanese, the effectiveness of the marriage shall be in accordance with the laws of Japan. |

||||||

|

��\�ܞ� �v�w���Y���n�����m�c���j���P���v�m�{���@�j�˃� �O���l�J���ˎ�g���v������ਃV���n���{�l�m���{�q�gਃ��^���ꍇ�j���e�n�v�w���Y���n���{�m�@���j�˃� |

Article 15 The spousal property system shall be in accordance with the home country law of the husband at the time of the marriage. In a case in which a foreigner effects a marriage with a female head of household, or becomes an adopted son-in-law of a Japanese, the spousal property system shall be in accordance with the laws of Japan. |

||||||

Purpose of Paragraphs 1 of Articles 14 and 15Paragraphs 1 of Articles 14 and 15 were not really necessary, since foreigners who became the entering husband of a female head-of-household, or an adopted son-in-law of a Japanese, became Japanese -- hence the applicability of Japanese laws in the case of the effectiveness of their marriages or the treatment of spousal property. I would guess that the paragraphs were included for the sake of clarification. They were deleted from revisions of the law after the Pacific War (see below). |

|||||||

|

��\�Z�� �����n�������^�������mᢐ��V�^�����j���P���v�m�{���@�j�˃��A�ٔ����n�������^�������J���{�m�@���j�˃��������m�����^���g�L�j��T���n�����m�鍐��ਃX�R�g�����X |

Article 16 Divorce shall be in accordance with the home country law of the husband at the time the facts of its cause engender [arise]. Provided that a court [in Japan] shall be able to effect a pronouncement [adjudication] of divorce when the facts of its cause did not exist pursuant to the laws of Japan at the time of the cause of divorce. |

||||||

|

��\���� �q�m���o�i�����ۃ��n���o���m�c����m�v�m���V�^�����m�@���j�˃��e�V���胀��V���v�J�q�m�o���O�j���S�V�^���g�L�n���Ō�j���V�^�����m�@���j�˃��e�V���胀 |

Article 17 Whether a child is of legal issue, or not, shall be determined in accordance with the laws of the country to which the husband of the mother belonged at the time of its birth. If the husband died before the child's birth, then its [legitimacy] shall be determined by the laws of the country to which he last belonged. |

||||||