Zaitokukai and the Japanese roots of Zainichiism

Special Permanent Residents as a caste of descendants of former Japanese

By William Wetherall

First posted 2 April 2017

Last updated 15 April 2017

Terminology

Korea/Koreans, Chosen/Chosenese, and Chorean/Choreans

Zaitokukai vs Zainichiism

The origins of Zaitokukai

•

Disillusionment and moving on

•

Zainichiism vs. Nationalityism

•

What's in a word?

•

Notes

•

Contributors

Related article

"Zainichiism": The racialist legacy of a divided "liberation"

SourceThis article is a reformated and hyperlinked version of the following articles.

William Wetherall The "Introduction" is reproduced here because it contains the statement on "Terminology" that applies to both parts of the general article.

William Wetherall and Mark Schreiber Text and notesThe following text and notes are as published. Japanese terms are romanized without diacritics and generally without other representations of vowel stretching. Only the titles of books, newspapers, and magazines are italicized. There is no Japanese script. All uncolored text in [brackets] or (parentheses) is as published. All bracketed [purple text] has been added. Images, hyperlinks, commentsImages of main publications mentioned in the article, hyperlinks, and boxed comments have been added. |

Tabloid nationalism and racialism in Japan

By Mark Schreiber and William Wetherall

1. Introduction: History and terminology

By William Wetherall and Mark Schreiber

In separately authored reports we examine some examples of nationalism and racialism, related to Japan-Korea relations and social problems in Japan, in tabloidesque print and electronic media in Japan. Both reports involve historical issues, which are supposed to be the province of history. Our reports are not about the issues, however, but about how states, advocacy groups, and individuals cook and serve the past to feed one or another school of history or life today. The past itself remains undigested as people argue, and even take to the streets over what happened and why, and over the consequences.

Terminology

If words matter -- do we speak of comfort women, sex slaves, or prostitutes, or do we use such terms as we find them? Do we differentiate Koreans, Chosenese, and Choreans in Japan, as people do in Japanese -- or label them Zainichi, as some people do but others don't -- or racialize them as "ethnic Koreans", an English expression which has no foundation in Japanese? Do we use "North Chosen" and the "Democratic People's Republic of Chosen", which reflect Japanese usage -- or "North Korea" and the "Democratic People's Republic of Korea", which favor English reductions of the distinctions between "Korea" and "Chosen"? And what do we call speech or actions that the speakers and actors call criticism or satire, but their dissenters call hate?

Many English sources conflate different Japanese terms or morph them into different metaphors. Writers and editors do this to simplify the stories, comply with a style sheet, or conform to customary or ideological usage. This often results in misinformation or distortion. We respect the diverse voices of our sources and the ability of our readers to hear them as spoken. To this end, we translate all Japanese expressions into English equivalents that preserve their distinctions and metaphors. We comment on their meanings when necessary.

"Tabloid" is our word for any conveyance of news, information, or opinion about an issue or topic in a sensational, provocative, or gossipy manner, irrespective of the medium or whether journalistic or academic. We use "nationalism" in the generic sense of "nashonarizumu" in Japanese. It can mean anything from "love of country" (aikoku), to the blood-and-soil "ethnonationalism" (minzoku-shugi) that generates much of the emotional heat in tabloid narratives of history.

Different words for different things have different meaningsWhy English needs to emulate Japanese metaphors when talking about JapanZaitokukai and the Japanese roots of Zainichiism represents my first attempt to systematically and consistently abandon the common practice, in English, to use "Korea" and "Koreans" -- or "ethnic Koreans" in reference to "Koreans in Japan" without heed to the distinctions made in Japanese between various real and fictive peninsular entities and their affiliates. For many years, I have been differentiating between "Kankoku/Kankokujin" and "Chōsen/Chōsenjin", each of which has various meanings depending on historical period and writer. This time I added "Koria/Korian" to my list of words that require differentiation, and they too may be used in different ways that defy singularization of meaning. I have long been aware that, when it comes to personal identity, the same individual may consider oneself "Kankokujin" or "Chōsenjin" or "Korian" in different situations, or two or all three of these in one or another situation, for reasons totally logical to those who understand what these words can mean to those who have every right to freely use them to label themselves -- without apologies to bureaucrats who deal only with formal civil statuses, or to academics whose theories of history and society do not accommodate reality, or to journalists and editors trained to slap fashionable style book labels on people with no thought about actual conditions. When it comes to writing about Japan in English, even those who understand the distinctions are apt to reduce them to simple, cozy, highly Anglicized, one-shoe-fits-all labels. In sharp contrast, any knowledgeable person who speaks or writes in Japanese -- or Korean or Chosenese, or in Chinese for that matter -- cannot avoid differentiating between at least "Korea" (Kankoku 韓国) and "Chosen" (Chōsen 朝鮮) in reference to various entities associated with the "Korean" or "Chosen" peninsula, and "Koreans" (Kankokujin 韓国人) and Chosenese (Chōsenjin 朝鮮人) in reference to the various people affiliated with one or another peninsular entity, past or present, state or territory, recognized or unrecognized, legally real or fictive, or simply imagined. "Chorea" (Koria コリア) and "Choreans" (Korian コリアン) often -- not always -- refer to a imaginary supra-state "country" and "nation" consisting of at least the Republic of Korea (ROK) and the Democratic People's Republic of Chosen (DPRC). Some writers in English use "Corea" and "Coreans" to embrace both states and their people, and rank the unified country higher than "Japan" in the the alphabetic order of nations. I prefer "Chorea" and "Choreans", the "chor" of which can be pronounced either as in "chore" or as in "chorus", which makes the label suitably fuzzy and ambiguous. The object is to faithfully reflect the metaphors of Japanese terms in English. What these terms actually refer to in specific contexts is another matter. |

Tabloid historyThe age of emotionalized history in the guise of factual history"Tabloid history" is my term for the sort of history that is propagated in sensational, emotional, and nationalistic writing about the past, whether in periodicals or books, on the Internet, or in classrooms or halls of government. It is not synonymous with "popular history", which may be only a watered down version of objective, fact-based history . "Tabloid history" by definition selects, weighs, and qualifies facts in highly subjective ways that generally serve nationalistic or other ideological purposes, rather than strive for understandings that transcend patriotic or other interests. Good examples can be seen in the standoff between "denialists" and "accusationists" in the battle over the history of Japan's imperialist adventures in East Asia and the Pacific, before and during World War II. See the following articles for details. Where are the historians?: A cry in the wilderness of victimhood history |

2. Anti-Korea nationalism in Yukan Fuji and rumors of bullying in America

Mark Schreiber

See Chapter 15 in Jeff Kingston (editor), Press Freedom in Contemporary Japan (London: Routledge, 2016), for this article.

3. Zaitokukai and the Japanese roots of Zainichiism

By William Wetherall

The word "Zainichi" inherently designates "foreigners in Japan" (Zainichi gaikokujin), but in status quo Japan it is used as a word to designate "Zainichi = Koreans/Chosenese in Japan (Zainichi Kankokujin/Chosenjin)". Seeing just this you can understand how peculiar the existence of Koreans/Chosenese in Japan (hereafter Zainichi) is. Foreigners who are neither migrants (imin) nor refugees (nanmin), in other words Zainichi, exist in Japan with special rights (tokken) called "Special Permanent Residence Qualification" (Tokubetsu Eiju Shikaku) (hereafter "Tokuei"). And these special rights called Tokuei permit residence in Japan practically unconditionally to Zainichi, and moreover permits even their children and grandchildren -- Zainichi 10th generation, 100th generation -- to inhabit and live off [Japan] (sumitsuki kisei suru) for as long as Japan continues to exist.

This erroneous definition of "Zainichi" -- an imprecise term that has no legal currency -- is the work of lexicographers in the Association of Citizens Who Will Not Tolerate Zainichi Special Rights (Zainichi Tokken o Yurusanai Shimin no Kai). Zaitokukai was established on 2 December 2006 to publicize the misgivings its members have about the favoritism shown some aliens in what I call the SPR Law, which in 1991 defined Special Permanent Residents (Tokubetsu Eijusha) or SPRs. Zaitokukai's founder, Sakurai Makoto (b1972), promised he would disband the group when the SPR Law was repealed. He needn't worry, though, as within his own lifetime, the law will die of natural causes, for SPRs are rapidly approaching extinction.

Zaitokukai's notoriety peaked in domestic and global print and electronic media in 2013. By 2015, the group had retreated from the streets -- along with the anti-hate groups that had formed to oppose the way Sakurai and a few others had been expressing their scorn and disdain for the people Zaitokukai's definition equates with parasites who have special rights. Zaitokukai's claims are of the rotten-apple-in-the-barrel kind that are made by people who simply don't like apples. In Sakurai's vocabulary, "good Zainichi" is an oxymoron. He also believes that under present conditions "Zainichi" should not be allowed to naturalize -- that making it easier for them to become Japanese is itself an intolerable "Zainichi special right".

In this report, I focus on two individuals whose encounters with Sakurai have been very different. The object will be to understand why many conservatives and even some liberals -- who reject hate speech, racism, and inequality -- question the merits of maintaining the SPR Law decades after the Occupation of Japan (1945-1952), when the population it defines as a virtual caste originated. I will also briefly touch upon the "hate speech" issue that caught and then lost public attention along with Zaitokukai. I will not, here, discuss the political, social, or legal history of Koreans and Chosenese in Japan, or the SPR Law and SPR demographics. [Note 2]

|

See the following articles for details. Territorial settlements: ROC and PRC, ROK and DPRK, and the USSR and Russia (The Sovereign Empire) |

The origins of ZaitokukaiWhen accepting his election as Zaitokukai's first chairmen on 20 January 2007, Sakurai Makoto spoke about its political stripes, grievances, and mission. "Shimin no Kai" (association of citizens) has left-wing connotations, he said, but the name is intended to stress that Zaitokukai is a citizens group (shimin dantai) (applause). There are about 600,000 Zainichi -- 1,000,000 if you include naturalized (kika shita) or latent (senzai-teki-na) Zainichi. They claim to have been forcibly brought, but practically all came to and remained in Japan on their own volition. Disproportionately large numbers are yakuza and welfare recipients, he also said, citing statistics. He opposed both Korea-related (Kankoku-kei) and Chosen-related (Chosen-kei) schools but especially the latter. They follow the curriculum of North Chosen (Kita Chosen). 5 bad Japanese soldiers cross a river. Chosen soldiers kill 2 of them. How many Japanese soldiers are left? The students shout Long Live Kim Jong Il, then scream discrimination when a Japanese university refuses to accept them. Zaitokukai seeks to rectify this, Sakurai said, then surrendered the mike to Mikage Soshi, one of two deputy chairmen. Mikage stated that email from Zaitokukai members, and Internet forums, show a shared anxiety (fuan) and fear (osore) about issues that people found scary (kowai) and terrifying (osoroshii) -- especially the history problems (rekishi mondai) with Korea. And it seemed Zainichi were using these problems and fears to abuse their special rights. Arai Kazuma (b1978), the other deputy chairman, took the podium. I'm Arai of the Chosen race (Chosen minzoku no Arai desu) [Chosen (ethnic) nation]. I first knew I was Zainichi when I was in elementary school. As for receiving special rights on account of being Zainichi, I myself didn't. [But] looking [at this] objectively, it is a fact that [North Chosen related] Soren and [Korea related] Mindan have interests (riken) as pressure groups (atsuryoku dantai). And I want to rectify this as [someone of] the same race (onaji minzoku). As for what sort of position [Zainichi] should go about living in Japan's society, from the Zainichi side -- I naturalized and am a Japanese (kika shite Nihonjin nan desu) -- but I'd like to ask [this] from the Zainichi side. |

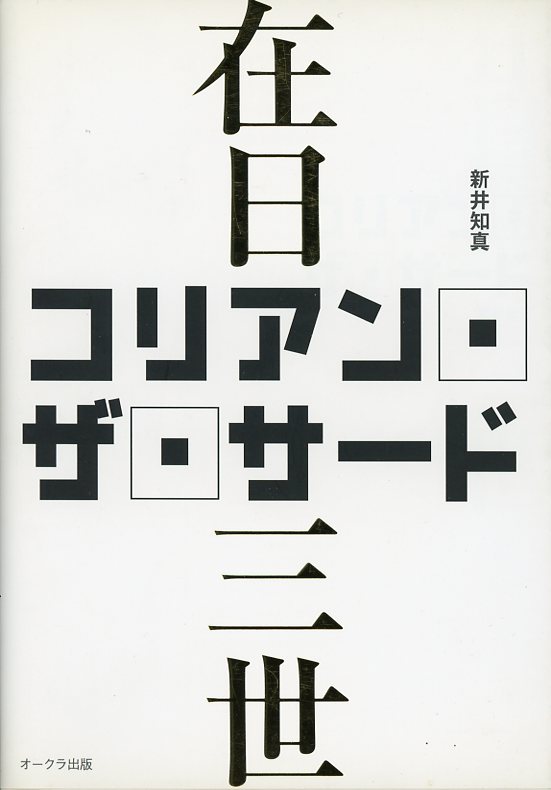

Disillusionment and moving onOn 2 December 2007, Arai notified Zaitokukai that he had decided to leave the organization. He said he had begun to question its principles and ways, and had come to the conclusion that the SPR qualification was not a "special right" but a right that "Zainichi Koreans and Chosenese" have as a matter of course -- "unlike other aliens, for whom the qualification is not recognized", he added, incorrectly. He also cited his personal environment and health problems as reasons for quitting. On 8 December, Zaitokukai's other officers, regretting that they were unable to talk him out of leaving, accepted his resignation, expressed their appreciation for his great contribution to the organization's development and his year of service as its vice president in charge of IT, and wished him well. By the end of April 2008, four months later, Arai had taken down his popular "koreanthe3rd" blog. His interests in the "Zainichi question" (Zainichi mondai) were practically gone, he said when announcing its deletion. He wanted to devote his time to his work and private life. In the meantime, a number of Koreans and Chosenese, and Japanese who used to be Koreans or Chosenese, have continued to be openly critical of the stances and activities of certain Korean and Chosenese activists, and of pro-Korea and pro-North Chosen interest groups. In Japan, as in other societies, water is thicker than blood. Arai did what hundreds of thousands of Koreans and Chosenese in Japan have done since 1952, when remnants of the Japanese progenitors of the SPR population, defined in 1945, lost Japan's nationality. After molting into a "Zainichi" cocoon that was not of his making, he emerged a Japanese and flew off with an identity that made more sense to him. Arai tells his story in 3rd Generation Zainichi (ZAINICHI Korian za saado SANSEI, Tokyo: Ookura Shuppan), a collection of his "koreanthe3rd" posts from December 2004 through November 2005. The book was published on 2 December 2006, the day Zaitokukai was born. It is a very insightful account of his life and thoughts (and afterthoughts) as he considered, and then finally applied for, permission to naturalize. Arai possessed (then) the nationality of Korea (Kankoku no kokuseki), and to that extent he considered himself a "Zainichi Korean" (Zainichi Kankokujin). But it meant nothing to him. He regarded himself as being of the Chosen [ethnic] nation [race] (Chosen minzoku) but stated that he had no sense of having Chosen [ethno] nationality [ethnicity, raciality] (Chosen no minzokusei). Upon naturalizing, he would consider himself a Chosen-descent Japanese (Chosen-kei Nihonjin) -- referring to the Chosen peninsula as the geographical territory that had been a part of Japan from 1910 to 1945/1952. [Note 3] Arai feels that there is no relationship between [ethno] nationality [ethnicity] (minzokusei) and [civil] nationality (kokuseki). He didn't say so, but following his logic, if he were to claim to possess a "minzokusei" (ethnonational character, ethnonationality, racioethnicity, raciality, ethnicity), then it would have to be "Japanese" -- defined by the language, culture, and society into which he was born and raised, hence his sense of being at home in Japan, and even his politics. Koreans who complain about Japanese prime ministers who visit Yasukuni Shrine, he says, should be the first in line to honor the spirits of the Chosenese enshrined there . . . as Japanese, he could have added. Sakurai himself, as of 1 December 2014, left Zaitokukai after serving 4 successive 2-year terms as its elected chairman. His pretext for leaving was to allow the group to go forward without the burden of his legacy. Prominent rightists had joined leftists in condemning his contempt for Koreans and Chosenese as racism and xenophobia. And court decisions against him, and against Zaitokukai largely because of him, constituted a political liability. Most conservatives seem to accept the SPR Law and SPRs as a legal fait accompli of politicolegal settlements following World War II. The main issue is whether SPRs -- aliens treated almost but not quite the same as Japanese -- should be allowed to vote and otherwise be treated entirely like Japanese while remaining aliens. Only 70 percent (and every year fewer and fewer) Koreans/Chosenese are SPRs. While 98 percent of SPRs are Koreans or Chosenese, the other 2 percent represent nearly 50 other nationalities, and some SPRs are stateless. People I call "nationalityists" -- including some former SPRs -- insist that SPRs who want to vote should become Japanese. Some "Zainichi SPRs" I call "Zainichists", though, insist that SPRs already constitute a subcategory of Japanese because they originated as a Japanese population. |

Zainichiism vs. NationalityismLee Sinhae (b1973) wears chogori at press conferences, and represents her multiple names in multiple scripts and dialects, including those of Pyongyang (Ri) and Seoul (I). I am spelling her name here as she represents it in alphabetic script as the author -- Lee Sinhae / Ri Shine -- of her autobiographical Tsuruhashi tranquility: An anti-hate chronicle (Tsuruhashi annyon: Anchi heito kuronikuru, Tokyo: Kage Shobo, 17 January 2015). Lee, like Arai and Sakurai, gained her following as an Internet activist. Unlike Arai, with whom Sakurai cultivated a working relationship, she became the favorite target of a number of anti-communist netizens, including Sakurai. Speaking at Zaitokukai's inauguration ceremony, Arai seemed uncomfortable on stage. Sakurai thrives on public exposure and creates his own limelight. Lee has family and other reasons not to vilify the Kim dynasty in Pyongyang, and this has made her a lantern for anti-North Chosen moths like Sakurai. She doesn't seem to relish public scrutiny, but she faces the spotlight when it turns on her, and in many videocast debates she has been an anvil to the hammers of her adversaries. Lee espouses one of the three schools of what I call "Zainichiism". The most fashionable school, adopted by race-box fanatics like Sakurai and some (including foreign) journalists and academics, use "Zainichi" (which some writers in English reflexively racialize as "ethnic Koreans") to embrace all people in Japan who have a drop of putative "Korean" or "Chosenese" or "Chorean" (Korian) blood in their veins. The second most common school uses "Zainichi" in the manner of Zaitokukai's definition, as a pronoun for all Korean/Chosenese aliens in Japan, and erroneously equates them with SPRs. Lee's brand of Zainichiism comes the closest to making legal sense in a civil society that takes historical statuses seriously. Nationalityists don't like it because its proponents advocate that SPRs should be allowed to vote like Japanese -- which threatens the commonsense notion of nationality as a fundamental requirement for participation in a state's popular sovereignty. In a 16 November 2013 marathon discussion on Channel Sakura's So-TV, focusing on the "Zainichi question", Lee responded to provocative queries about her "identity" (aidentiti) by Murata Haruki (b1951), a political activist with ethnonationalist leanings who opposes suffrage for aliens. Murata said some non-SPR Koreans feel that giving other Koreans special rights simply because they have been in Japan longer is discriminatory. Lee contended the rights weren't special but a matter of course. Murata countered that they were provided, and that taking them for granted was wrong. Murata spoke of Koreans/Chosenese SPRs who when overseas seek help at the Japanese consulate in ROK or a Japanese consulate in America because they can't speak Korean. "What are they?" he said. "They're not Japanese Koreans (Japaniizu Korian), not Nikkei Kankokujin. So what are they?" "Zainichi Koreans", Lee said. "In that case," Murata said, "shouldn't they abide by Korea's laws, have contact with Korea's culture, read Korea's papers, watch Korea's news, and vote in Korea's elections?" "Zainichi. We're Zainichi," Lee said. "So you're foreigners," Murata said, still baiting her. "Zainichi. Not foreigners," she said. "We're Zainichi." Lee's insistence that she is not an alien but a "Zainichi" -- as though "Zainichi" was a nationality in its own right -- was greeted with amusement by others around the table, including two other Korean/Chosenese SPRs. Her Internet detractors immediately mocked her remark. But even Murata understood exactly what she meant, whatever he thought of her "we Zainichi deserve to be treated like Japanese" attitude. Lee, in stressing that "Zainichi" progenitors had been Japanese, implicitly asks: How can people whose lives in Japan span over 70 years and at least 4 generations -- and whose roots in Japan go back over a century to people who until 1952 had been Japanese -- be treated like aliens? Lee's nationality (kokuseki) is Korea (Kankoku), but she calls herself a 2.5 generation Zainichi Chosenese (Zainichi Chosenjin 2.5-sei). Like Arai and some others, she celebrates her descent from the population of Chosenese who lost Japan's nationality in 1952. Like Arai did at times in his book, she too has sometimes called herself a "Zainichi Chorean" (Zainichi Korian) -- while adding that she is neither a Korean nor a foreigner. She has also said she thinks that "everyone with Chosen peninsula roots is ‘Zainichi'" (Chosen hanto ni ruutsu ga areba minna "Zainichi" da) -- whatever this means. Unlike Arai, though, she won't be able to participate in Japan's political society if she clings to her SPR status and people opposed to alien citizenship, like Murata, have their way. The SPR Law, and the Constitutional limitation of national sovereignty to nationals of Japan, will probably stand. And the standoff between nationalityists and SPR Zainichists will wane by the middle of this century, when there will be only a few or no Special Permanent Residents remaining. |

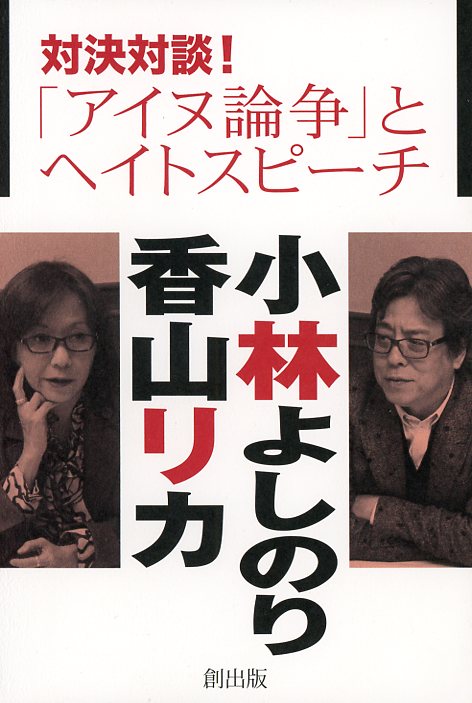

What's in a word?Some people may feel that the last line of the definition cited at the outset of this report constitutes hate speech (heitosupiichi), because it likens "Zainichi" to parasites that have taken up long term residence -- as though to suggest that it's time to eradicate them. At a hate-speech symposium in 2015, Kise Takayoshi (b1967), a "counter hate speech" (han-heitosupiichi) activist, objected to the titles of two separately authored but similarly titled books -- 100 questions and 100 answers to permanently silence [China] [Korea・North Chosen] -- published by WAC. "What is the best way to permanently silence (eikyu ni damaraseru) someone?" Kise asked Hanada Kazuyoshi (b1942), the "Right face, Right!" videocaster cum editor of WAC's monthly magazine WiLL, then answered his own question -- "Think a bit and you'll understand. It's genocide (jenosaido)." "Silence means to break someone's argument (ronpa) to the point they can't counter-argue (hanron)," Hanada told Kise. "To read this in a way that links it with genocide is warped. Do you not understand even that much Japanese? Your way of reading is wrong." During 2013, Japan witnessed a scattering of widely publicized demonstrations, some in Osaka's and Tokyo's "Korea towns" (Koria-taun), involving hate speech. Groups opposed to "Zainichi special rights" and alleged abuses clashed with groups that denounced the allegations and the xenophobic manner in which they were often made. Most demonstrators on all sides peacefully waved flags and banners and placards and left the dirty work to the thuggish elements in their ranks. Some "special rights" objectors chanted "Cho-sen-jin, KO-RO-SE!" (KILL Chosenese!). Some "counter-racist" (tai-reishisuto) activists brandished "Heito buta, SHI-NE!" (Hate pigs, DIE!) signs, sporting images of Zaitokukai's founder and then chairman Sakurai Makoto, or flipped middle fingers and flashed tattoos. Passersby who didn't know what was happening might have thought they had stumbled into a rumble between two gangs. By the end of 2015, Japan's social and legal immune system had stopped this outbreak of a virus that had been incubating in Japan since the Allied Occupation from 1945 to 1952, and continues to fester in remission. The anti-"special rights" protests began shortly after Zaitokukai's birth in 2006 and escalated. They stimulated widespread anti-hate vigilantism, and inspired numerous anti-hate publications and Internet initiatives. A Supreme Court decision against Zaitokukai and some of its members in 2014, and a warning issued by the Ministry of Justice in 2015 directly to Sakurai, by then no longer a member of Zaitokukai, have also been effective in keeping intolerance in Japan within the tolerable limits of what I call "normal pathology" -- the price of freedom in a democratic society. Japan's laws -- including the Constitution, the Civil Code, the Penal Code, and a number of international conventions -- have provisions that broadly proscribe racial discrimination, and the sort of physical and verbal acts that are typically motivated by hate. All have been applied in court precedents favoring victims. In response to public expressions of hatred and intolerance by some Zaitokukai members and others, a few municipalities have passed ordinances that proscribe "hate-speech". On 24 May 2016, the National Diet passed a bill for a "Law concerning the promotion of initiatives directed at the elimination of inappropriate discriminatory speech and behavior toward persons originating outside this country (honpou-gai shusshin-sha)." The law was promulgated and came into force on 3 June 2016. The "national-origin and anti-discrimination law", as I call it, recognizes the responsibility of the national government to work with local governments to promote an awareness of the unacceptability of verbal and other acts that express contempt for, or advocate the exclusion from society of, people whose national origins are other than Japan and their descendants, who are legally residing in Japan. Since this also covers Japanese of putatively foreign ancestry, the law does not need to specify nationality. Nor does it need to racialize national origin, avoidance of which is consistent with Japan's objections to the racialization of national origin in some other countries. Key wording in the law mirrors the phrasing of an article in the Penal Code that defines crimes of intimidation. The law thus makes it easier to enforce standing laws that have already been applied to egregious xenophobic acts, without empowering the state to police racial identity, race relations, or related thoughts. Defenders of free speech condemn hate speech, but worry that arming the government with censorship laws would discourage or muzzle questioning the legitimacy or the behavior of any legally defined or self-styled group that feels it deserves special rights or protection from criticism. The manga writer and author Kobayashi Yoshinori (b1953) doubts that Ainu constitute a bona fide "[ethnic] nation" or "race" or "people" (minzoku), and he questions "Ainu interests" (Ainu riken). But the psychiatrist, writer, and TV personality Kayama Rika (b1960) equates Kobayashi's attitude toward "Ainu" with denialism and hate speech. So what do they do? Kobayashi and Kayama, who make their livings on social and political commentary, staged a civil showdown in "The Ainu Debate" and "Hate Speech" ("Ainu ronso" to "Heitosupiichi", Tokyo: Tsukuru Shuppan, 5 June 2015). The book dramatizes the difficulty of questions like what constitutes a minority [ethnic] nation (shosu minzoku), and whether people who identify as Ainu deserve special treatment in the age of equality. It also exemplifies a healthier alternative to authoritarian laws that could terminate thought. If Lee were to accuse Sakurai of being a professional demagogue, he would call her a professional victim. In 2014 she sued him for things she alleges he said about her that she considers hateful. In 2015 he countersued her for things she supposedly said that he claims are malicious. I give her my moral support and a slight legal edge. Yet I feel that the issues both litigants raise would be better addressed in public debates with thicker skins and more humor.

|

Notes

- For more information, including primary sources related to this report, see relevant articles on my Yosha Bunko website.

- "1945/1952" denotes the period between Japan's loss of Chosen, Taiwan, and other territories when it surrendered in 1945, and its renouncement of all "right, title, and claim" in the peace treaty that came into effect in 1952. Since Japan's nationality is linked to household registers within its sovereign territory, Chosenese and Taiwanese domiciled in Japan remained Japanese during this period.

Contributors

Mark Schreiber, born in the United States in 1947, is a permanent resident of Japan, where he has resided and worked most of his adult life as an advertising copywriter, freelance writer, and translator. He is best known for his books on crime in Japan, reviews of English popular fiction set in Asia, and nearly 35 years of columns, in monthly magazines published by the PHP Institute, and in the Mainichi Daily News and now in The Japan Times, digesting and commenting on articles in Japan's weekly magazines. His investigative reports on the anti-Korea stance of some Japanese newspapers and magazines, and on political uses of the comfort-woman issue, have appeared in the Number 1 Shimbun, published by the Foreign Correspondents' Club of Japan.

William Wetherall began life in the United States in 1941 but has resided most of his life in Japan, now as a Japanese national. An independent scholar and freelance writer, he has published numerous articles and stories in newspapers, magazines, journals and books, on suicide, race and ethnicity, migration and mixture, nationality, classical and contemporary literature, comics, news-related woodblock prints, early and recent history, and nationalism. He has also published translations of a few works of Japanese fiction and a number of his own short stories. His publications, including a couple of collaborations with Mark Schreiber, are posted on his Yosha Bunko, News Nishikie, and Steamy East websites [and Konketsuji and Wetherall sites].