Shinsen Shōjiroku

"Newly compiled record of titles and families" in 815 Japan

By William Wetherall

First posted 10 September 2019

Last updated 10 September 2019

Shinsen Shōjiroku

Title

•

Date

•

Compilers

•

Publishers

•

Preface

•

Tenmu's 684 kabane decree

Wabon editions

Shirai 1668 (NDL)

•

Matsushita 1669 (WUL)

•

CiNii listed copies

Yosha copies

Hashimoto / Motoori 1807 / 1834 (Yosha)

•

Kosugi 1876 / Shirai 1668 (Yosha)

Studies

Hirota (Meiji)

•

Saeki (1960s-1990s)

•

Miller (1974)

•

Suzuki (2000s-2010s)

•

Kanagawa (2010s)

•

Myself

Who's who where

Heiankyō

•

Kinai provinces

•

Uji (clans, families)

•

Kabane (titles)

•

Statistics

Kudara (Paekche) kings

Discrepancies in generation counts

Related articles on this website (New windows)

Allegiance change in Yamato: How natives and migrants joined the fold

Becoming Japanese in the Meiji period: Adopted sons, incoming husbands, and naturalization

Reports from early records: Natives and barbarians at the dawn of Japanese history

Kofun through Nara • 300-794: Conquest, incorporation, integration, and security

Soga and Fujiwara wombs: The violent birth of Yamato harmony

Akihito's Korean roots: The Fujiwara embrace of Kudara

Shinsen Shōjiroku

The most significant population register in early Japan was the Shinsen Shōjiroku (Vï©^), a peerage compiled in the early 9th century and published around 815. According to this register, about thirty percent of all kabane-titled families clans in the vicinity of the Heian capital in present-day Kyōto were of peninsular or continental origin. By then, significant migration from the peninsula had stopped. Families had mixed. Old families had faded and new ones had emerged. The passage of time and memory made it increasingly difficult, if not pointless, to keep track of lineal origins that no longer seemed to matter. To the compilers of Shinsen Shōjiroku, however, the origins of a family -- never mind the family's title, and the role the family played in the social and political scheme of things -- mattered.

New compilation of what?

"Shinsen" or "Newly compiled" in the title of Shinsen Shōjiroku suggests that there was an earlier Shōjiroku that needed updating. But academic consensus is that there was no precursor -- no earlier such listing of titled families. All that was "new" was the idea of compiling or "selecting" (ï) which titled families of many to include in what was actually a new undertaking.

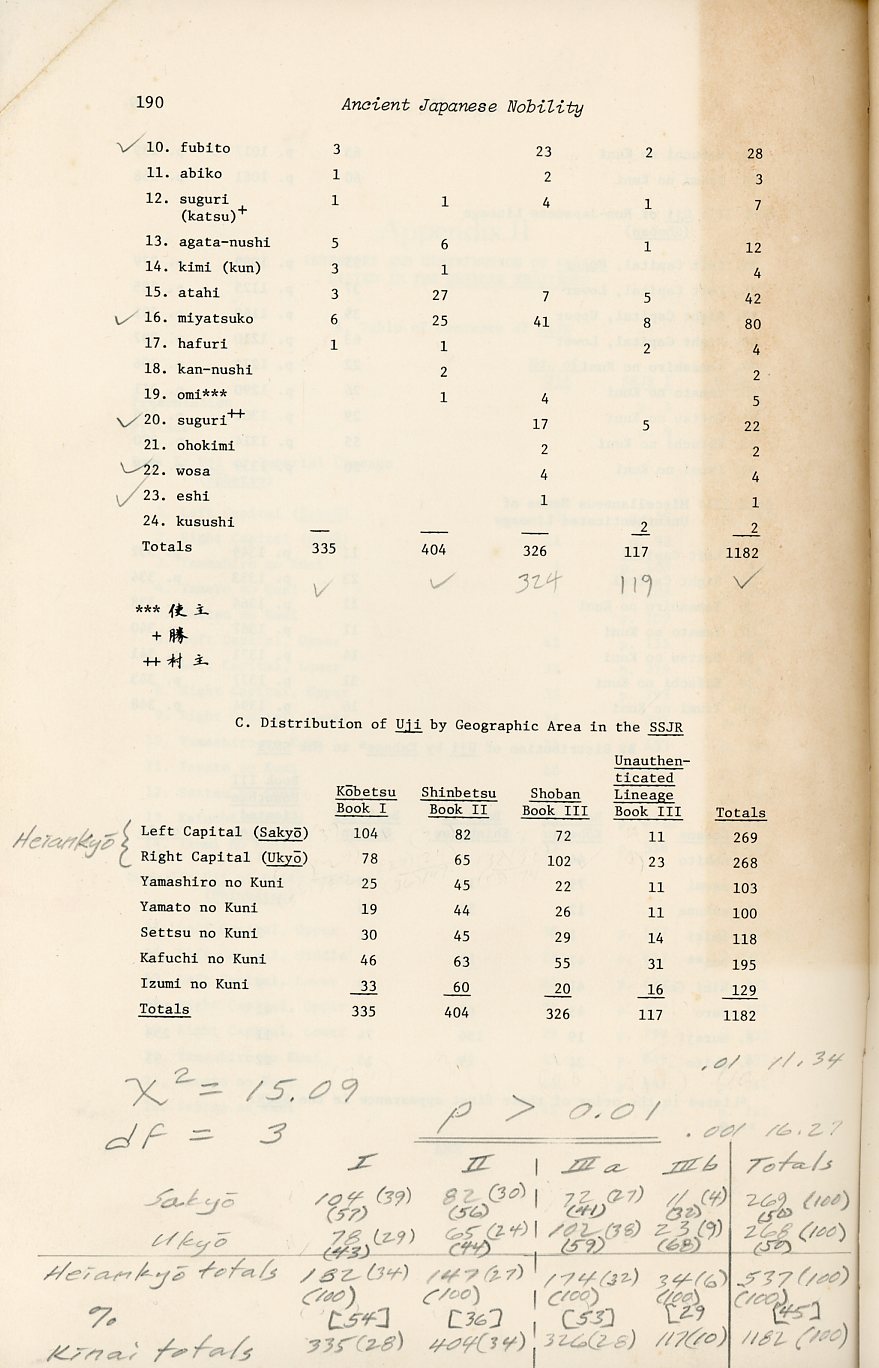

The 1,182 titled families included in today's "collations" of different versions of the work, were drawn from titled families in the Heiankyō capital and the nearest 5 Kinki provinces. There were many other such families in more distant provinces, but the distances of their residences from Heiankyō signified their lessor importance in the scheme of things that centered on the capital.

Shinsen Shōjiroku does not appear to have been updated since its publication in 815, which suggests that the concern of its compilers was not shared by later generations. And judging from what little survives of earlier copies, there does not seem to have been a lot of interest in the work -- until the early 17th century, 900 years after SSSR was compiled, when national studies scholars -- leading a renaissance of interest in the origins and early history of Japan -- began producing various collations of whatever editions were available and within reach. Interest in the work, and its implications for the nature and quality of early Japanese society, continued to inspire new collations after the start of the Meiji period in 1868, and during the 20th century. Today, in the 21st century, the work still stirs interest and controversy.

Titles

The full title, Shinsen Shōjiroku (Vï©^), is sometimes referred to by the short title, Shinsen Shōroku (©^), in copies of the work as well as by readers and researchers. Editions consisting of extracts may be titled Shinsen shōroku shō (Vï©^´).

I will sometimes abbreviate the title SSSR.

I am translating the title "Newly compiled record of titles and families" to reflect all elements of the Japanese title. While Vï is dubbed "new compilation" it could just as well be "new selection".

The expression © (shō) is rendered "titles (© shō, kabane) and families ( ji, uji)". This could be interpreted as "titled families", since the object of the record is to account for families with a title bestowed on the family by the court. Putting "titles" ahead of "families" reflects the face that the family name of a titled family is preceded by the title.

New "compilation" or "selection" of what?

"Shinsen" or "Newly compiled" in the title of Shinsen Shōjiroku suggests that there was an earlier Shōjiroku that needed updating. But academic consensus is that there was no precursor as such -- no earlier register or other such listing of titled families. All that appears to have been "new" was the idea of "compiling" or "selecting" (ï) which of many titled families to include in what was actually a new undertaking.

Dates

The date given at the end of the foreword is precisely OmZNµñ\ú -- Kōnin 6-7-20 -- 815-9-1.

However, Book 23 of Nihon kōki (ú{ãN) -- which has been lost -- reported the completion of SSSR by 814-6-25, according to the following report in the Nihon kiryaku (ú{Iª), a circa 1036 compendium of "Briefs of chronicles of Japan" cleaned from earlier national histories. I have copied, pasted, and formated the text from the J-Texts edition of Nihon kōki, which reconstructs some missing parts from Nihon kiryaku and other texts.

sOmÜNZ¸qñtZB¸qñBæ¥A±¨liäݽe¤AEåbnñÊ¡´©blAòºï©^B¥§¬Bã\HB]XBKōnin 5-nen 6-gatsu heishi tsuitachi [Kōnin 5-6-1 = 814-6-25]. First, Ministry of Central Affairs (Naka-tsukasa-kyō) Fourth Rank Prince Manda, Minister of the Right Junior Second Rank Fujiwara no Asomi Sonodo and others, presented the sovereign Sen Shojiroku, and reporting up (memorializing to the emperor) said, [it is] now finished (had come to this and was completed), and so forth.

Compilers

Pages 3a-3b ±¨libäݽ䓁(sic )e¤

EåbnñÊsc¾ísút¬Üb¡´s©btl

ÒcnOÊs{內¨ß]çb¡´©bû©(sic )k

³Üʺs¢¾(sic å)·¯sbt@¢©báÁ

nÜÊãsö£çbO´©bí½

nÜÊãsåOLö¦îbãÑ(sic)ì©bo(sic n)l䓁(sic )ã\

Fujiwara no Sonohito (¡´l 756-819) served the court under emperors Kōnin, Kanmu, Heijō, and Saga.

Fujiwara no Otsugu (¡´k 774-843) was the oldest son of Fujiwara no Momokawa (¡´Sì 732-779), Emperor Kanmu's father in law. He served the courts of emperors Saga, Junna, and Ninmyō. He was also a collaborating compiler of the Nihon kōki, the 3rd national history, which was commissioned by Saga in 819 and completed in 840. The history covered years 792-833.

Abe no Makatsu (¢áÁ 754-826) served emperors Kanmu, Heijō, and Saga. His family clan (shizoku °) was À{ (Abe shi), hence his name is commonly written À{áÁ (Abe no Makatsu).

Mihara Otohira (O´í½ bd unk) served emperors Kanmu, Heijō, and Saga.

Kamitsuke no Kaihito (ãÑìnl 766-821 Hidehito) served emperors Kanmu, Heijō, and Saga. His clan's name and title, formerly Kamitsukeno no Kimi (ãÑìNö), became Kamitsukeno no Asomi (ãÑì©b). The clan is supposed to have originated in Kudara. © ãÑìNiöj Ì¿ãÑì©b o© SÏnnl c ÌE|t£i½ïg¢Nj iLéüF½Ü¢·j íÊ cÊ {Ñ Ré¶ ãÑì©bnl i766N-821Nj - ]lÊãBgÉ^ƵÄÁíènBòqÌÏÉà÷BwVï©^xÒ[ÉQÁBw½_WxÉ1ñAwoWxÉ1ñ[15]B

Manta Shinnō et al.

The compilation of Shinsen Shōjiroku was undertaken under the supervision of Manta Shinnō -- Prince Shinnō -- the 5th son of Emperor Kanmu (737-806 r 781-806 50th) -- with

Manta was the half brother of Kanmu's first three successors, Emperor Heijō (½é 774-824 r806-809 51st) and Emperor Saga (µã 786-842 r809-823 52nd), who were full brothers born to Kanmu's principal wife Fujiwara no Otomuro (¡´³´R 760-790), and Junna (~aVc 786-833 r823-833 53rd), a half-brother born to Fujiwara no Tabiko (¡´·q 758-788), one of Kanmu's consort wives. Fujiwara no Tabiko was the oldest daughter of Fujiwara no Momokawa (¡´Sì 732-779), a veteran minister who had served a succession of tennō, including Empress Kōken (Fª 718-770 r749-758 46th), her successor Junnin (~m r758-764 47th), his successor Empress Shōtoku (Ì¿ 718-770 r764-770 48th), the former Empress Kōken, and her successor Emperor Kōnin (õm 709-782 r770-781 49th). Fujiwara no Momokawa is said to have advocated that Emperor Kōnin be succeeded by his (Kōnin's) eldest son, Prince Yamabe, in lieu of Prince Osabe, Yamabe's half-brother, who had been appointed Kōnin's crown prince. Fujiwara no Momokawa's posthumous influence was such that Yamabe, his son-in-law, would succeed Kōnin as Kanmu. And Kanmu's son with Fujiwara no Momokawa's daughter Tabiko -- i.e., Fujiwara no Momokawa's grandson -- would become Junna. Manta's mother, another of Kanmu's consort wives, was Fujiwara no Okuso (¡´¬ bd unk Oguso), a daughter of Fujiwara no Washitori (¡´hæ bd unk).

See Soga and Fujiwara wombs: The violent birth of Yamato harmony for the convoluted details of Kanmu's genealogy.

Shinsen Shōjiroku preface

Among the bibles of English-language sources on Japanese history were the two volumes of Sources of Japanese Tradition published by Columbia University Press in 1958. The 1st volume contains materials related to early Japan.

Tsunoda 1958

Ryusaku Tsunoda, Wm. Theodore De Bary, Donald Keene (compilers)

Sources of Japanese Tradition

Volume 1 [of 2 volumes]

[Introduction to Oriental Civilizations]

New York: Columbia University Press, 1958

Text edition in two volumes published 1964

Third printing 1967

xxiii, 506 pages, paper cover

The following introduction to the Shinsen Shōjiroku, and the translation of its preface, come from pages 85-86 and 86-88 of this work.

Introductory remarks

Sources of Japanese Tradition introduces Shinsen Shōjiroku as follows (Volume 1, pages 85-86, my formating and highlighting, numbered notes in original, lettered notes mine).

|

NEW COMPILATION OF THE REGISTER OF FAMILIES The importance of genealogy in determining claims to sovereignty was demonstrated by the Records of Ancient Matters (A.D. 712). The Japanese who thus stressed the divine descent of the imperial family, were confirmed in this by the Han view of the Mandate of Heaven as conferred, not on individuals, but on dynasties which themselves had been provided with genealogies going back to the sage-kings. However, in the following preface, in that to the Kojiki, and in several Taika edicts, there is evidence that Japanese family genealogies were in a great state of confusion until the seventh century, when Chinese histories were brought over containing well-ordered genealogies of important families. This no doubt inspired the Japanese to draw up similar records, not only of the imperial house, but of all important families. The New Compilation of the Register of Families (Shinsen shōji-roku, A.D. 815) is one result of this development. The influx of Korean and Chinese immigrants during the Nara Period and earlier had in some respects presented a challenge to the Japanese, for the immigrants were clearly superior to the Japanese in their knowledge of the techniques of civilization. The advantage that the Japanese claimed was their descent from the gods, and to this heritage they jealously clung. In the Register of Families, the names given are divided into three classes: "All descendants of heavenly and earthly dieties are designated as the Divine Group; all brances of the families of Emperors and royal princes are called the Imperial Group; and families from China and Korea are called the Alien Group." It perhaps seems surprising that the "descendants of heavenly and earthly deities" (who must have included a good part of the Japanese population) should have been mentioned before the imperial family. However, since these deities ruled over the land of Japan before the arrival of the imperial family from Heaven, they deserved their pride of place. |

I have reproduced the preface as received in my own wabon copy of Shinsen Shōjiroku below. I created the text by cutting and pasting the text in an on-line version and editing it to conform to my version. The on-line version was created by the process engineer and Miko-phile Huang Tsu-hung (©cø), aka Uraki Yutaka (YØT), who inputed the kanbun text from the following publication.

Ic°

Vï©^lØ

FgìO¶ÙA1900-1901

SQû (ª1-10Aª11-20)Aõø

§ï}ÙfW^RNV

Kurita Hiroshi

Shinsen Shōjiroku kōshō

[Documentary study of Shinsen Shōjiroku]

Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kōbunkan, 1900-1901

Two volumes (Books 1-10, Books 2-20), Index

National Diet Library Digital Collection

Kurita Hiroshi (Ic° 1835-1899) was a Mito domain national studies scholar (kokugakusha wÒ) who became a professor at Tokyo Imperial University. He is known for the work he continued to do on the massive Dai Nihonshi (åú{j), which was undertaken by Mito scholars from the middle of the 17th century.

|

Preface to Shinsen Shōroku |

|

|

Yosha Bunko wabon edition, folios 4a-10b |

Translation by Ryusaku Tsunoda |

|

(4a) Vï©錄 ÒæêÉVçBsÚ¯Ú錄B§ÚÉB W·AV·~P¼»VA_¢ÉJALêrBB_ÕĪVNAl¨Q AÔNBÁ_ºöAè˹°òAdñ¯wAQ¥¶UB(4b) ä^ó¾½AõîBA×K½êAC內´æBù§Þúºl÷Aãðy½B ¢AãpåAnåjzBm^A¨àV\VA¨[¾A©âcªBµCßAV d賮¢ÒA×ÂúºA³vsÒBå©A¥¾B(5a)ò±äFAäÝ©´ãABºÙ|A¿_TAñÒSA`虛ÒQB©玆ÎãA(++©©èAX³¼lA++)úûÍʬBcɬ¾A LFàAcãÀ´ª¹AàÂ{´U說BVqVc×{çADj¨V(►Ú)òiàBMßNAÒ¢戶ÐAl¯(5b)Ae¾´XB©玆È~A歷ãé¤Aç¬ü³AüÈs絕By ¶ z ó(►)NA(►Á)L¶|Aãã×ACèVBg歬(►O)©ã©A¶zW(►¯)A×a°^BäÝû¯AÂMV}tAOØ×oAâiú{(++V++)_ûBÚlÕA(6a)ã¥m§¾BVA´à¥PÉB¹聚(►Ù)¼òAï°uB´Ä¤¼A§LïAòðÌ(►é)Aço§s»Bc\ƹ¾A¶§bNA©é«mBÐíúoVRAúºõKVæBâàEJ(►è)A¶O×êB¶üi¨Avس¼B(6b)ç~ãNãdAï¨{nB緗ã¢LAP`oàêBy ¶ z V©¾AÐCOÆB(++¹++)³¹AáÅãdBà§勑(►Ã)±¨libäݽe¤AEåbnñÊscå(►¾)íúb¡´©blAÒc³lʺsEqåÂß]çb¡´(7a)(++©bkA³ÜʺsAzªb¢©b^A]ÜʺsAzªb¢++) ©b^AnÜÊãsö£çb(--b--)O´©bí½AnÜÊãsåOLö¦îbãÑì©bnlAÇç歬(►O)uAO¶AJ{VéåUAqVuBy ¶ z b歷TÃLAæVäpjA¶éo(►)ççCA¹Pg(§Ø+è°)(►è¶)B(7b)ðç×êAÒì|µG_說A¥Là°à±(►æ)BVi{nA½áÌB½ö_A¬×êcB½sm¹¬A|öcB½À¸ÈcAßü¼B½Iü¼AÈ×ÈcBVÃÏ(►ª)AsÕ(Ø?äÂ?)(►ä)ÎBÞTöAsÂÉB¥(úh+RR)(►È)(8a)å«~¬VsúA§P\歲ä¢BE{nA¢iß¼By ¶ z ¡Ë©iAÈÞFv(►áá)B{´³¶A¥LOá(►é),(++O´QªA¥LOá++)BV_n_Vð (►h)AàV_ÊBVccqV泒AàVcÊBå¿AOØV°AàV×BÈÊW(►¯)ÙA歬(►O)ã¥×Oé(8b)çB(++½ÃLA{nÀ錄Ú§++ ►A) }ÊV@Á§VcAH(►ñ)o©B(►A) ½ÃLA{nÀ錄Ú§錄§ÚA½ÚÃL§R{nA½Ú{n§RÃLAHW(►¯)cVãB@ÃLAå«]âRA§§csãx(►T)AA涉Ï^AHVãBÈßA¦eæñA¥×OáçB(9a)v¡à÷ÚØA®LàêßBµÁã¶(►¢)A叵m歬(►O)¢BÌcÌA¢ÉëA¥s×帢_§Ù¬B^l¥cÊVãçAó(►À)WEAÈ×êÉAcÊñB¢è¥V¢¾çAúÊ×êÉA×öBL©(9b)R{n§ÚÃLA¥´ÃLÈB{nVäoÃLáA¥(►)ÃLÈèB¡ÂVæø(►E)ÃLA¥å«¶éo(►)A§sKüAȶ´¶æçBçBEVAåéSâÄ (++B ++)VA½sKüEBy ¶ z bòÃAÞÁ¤(10a)¸A捃摭Q¾A¹¿àâIBÙäpLVÏAÌðVV@vBVnVh說ABÊÃVÜBvÈ߶ñç(►ð)ÕAâR¦¶Aà ÁwìBN©_AÁ(►°)OmB·(►溫)ÌmVA\eLB}êçêSª\ñAy×O\(10b)ÉBèÓ¬OA¼HVï©錄Bå«ñèèÒ^ÙV`AÊÂãDV¶A}([+灬)(►)lÏVâ@A ÆV櫽çBBE¢iA幷(►À) iÞAêïá¶Aè§sA´©ÚñÊÉ]¢B |

Preface in the Form of a Memorial to Emperor Saga They say that the Divine Dynasty had its inception when the Grandson of Heaven descended to the land of So [Note 1] and extended its influence in the West, [Note 2] but no written records are preserved of these events. In the years when Jinmu assumed command of the state and undertook his campaign to the East, conditions grew steadily more confused, and some tribal leaders rose in revolt. When, however, the Heaven-sent sword appeared and the Golden Kite flew to earth, [Note 3] the chieftains surrendered in great numbers and the rebels vanished like mist. Jimmu, accepting the Mandate of Heaven, erected a palace in the central province and administered justice. Peace reigned throughout the country. Land was allotted to men who were deemed virtuous in accordance with their merits. Heads of clans were granted such titles as Local Chieftain [Kuni-no-miyatsuko] and District Chieftain [Agata-nushi] for the first time. Suinin [Note 4] cultivated good fortune by his ever-renewed benevolent favors. Through such acts the Golden Mean was attained. [At this time] clans and families were gradually distinguished one from the other. Moreover, Imna (Mimana) came came under our influence and Silla (Shiragi) brought tribute. Later, barbarians from other countries, in due reverence for his virtue, all wished to come to Japan. Out of solicitude for these aliens, he bestowed family names on them. This was an outstanding feature of the time. During the reign of Inkyō, [Note 5] however, family relationships were in great confusion. An edict was accordingly issued, ordering that oaths be tested by the trial of boiling water. Those whose oaths were true remained unscathed, while the perjurers were harmed. From this time onwards the clans and families were established and there were no imposters. Rivers ran in their proper courses. While Kōgyoku held the Regalia, [Note 6] however, the provincial records were all burnt, and the young and defenseless had no means of proving their antecedents. The designing and the strong redoubled their false claims. Then, when the Emperor Tenchi was Heir Apparent, Eseki, an archivist of the Funa family, presented to the court the charred remains of the records. In the year of metal and the horse (A.D. 670) the family registers were re-compiled and the relationships of clans and families were all clarified. From this time on revisions were always made by succeeding sovereigns from time to time. During the Tempyō Shōhō era (749-57), by special favor of the court, all aliens who had made application were granted family names. Since the same surnames were given to the immigrants as Japanese families possessed, uncertainty arose as to which families were of alien and which of native origin. There were commoners everywhere who pretended to be the scions of the high and the mighty, and immigrant aliens from the Korean kingdoms claimed to be the descendants of the Japanese dieties. As time passsed and people changed scarcely anyone was left who knew the facts. During the latter part of the Tempyō Hōji era (757-65) controversies about these matteres grew all the more numerous. A number of eminent scholars were therefore summoned to compile a register of families. Before their work was half completed, however, the government became involved in certain difficulties. The scholars were disbanded and the compilation was not resumed. . . . [ellipsis in Tsunoda] Our present Sovereign, [Note 7] of glorious fame, desired that the work be resumed at the point where it was abandoned. . . . [ellipsis in Tsunoda] We, his loyal subjects, in obedience to his edicts, have performed our task with reverence and assiduity. We have collected all the information so as to be able to sift the gold from the pebbles. We have cleared old records of confusion and have condensed into this new work the essential facts contained in them. New geneologies have been purged of fictitious matter and checked with the old records. The concision and simplicity of this work are such that its meaning will be apparent as the palm of one's hand. We have searched out the old and new, from the time of the Emperor Jimmu to the Kōnin era (811-24) to the best of our abilities. The names of 1,182 families are included in this work, which is in thirty volumes. It is entitled the "New Compilation of the Register of Families." It is not intended for pleasure-reading, and the style is far from polished. Since, however, it is concerned with the key to human relationships, it is an essential instrument in the hands of the nation. |

|

Notes on Japanese text |

Notes to English text

|

Emperor Tenmu's 684 kabane decree

The Nihon shoki (ú{I), also known as Nihongi (ú{I), usually called "Chronicles of Japan" in English, is a chronology of Japan from from its mythological origins to the 697 in the Christian era. It was completed in 720 (Yōrō 4) in 30 books (kan) and a genealogy, compiled by Prince Toneri (Éle¤ 676-735), and later also partly attributed to Oo no Yasumaro (¾Àäݵ d723). As such it is the first of Japan's six early national histories.

As of this writing (2019), there are several Japanese versions of the original and various Japanese translations, and Aston's English translation, in print). There is also a full English translation with two versions of kanbun texts (including the J-Texts version) on a "Wiki Site" called nihonshoki.wikidot.com. The on-line English text is convenient for quick reading, and may be an improvement over Aston's rendering. However, it is not more reliable as a guide to the metaphors in the original and has few notes.

For my purposes, I have used the following Nihon Koten Bungaku Taikei (NKBT) edition and Aston's translation to facilitate my own translations of excerpts.

NKBT 67, NKBT 68

There are numerous scholarly and popular guides to Nihon shoki. This NKBT edition, edited by an allstar cast of historians and linguists, continues to be an adequate standard if used with care.

Sakamoto Tarō, Ienaga Saburō, Inoue Mitsusada, and Ōno Susumu (translators and annotators)

Nihon shoki

[Chronicles of Japan]

Nihon koten bungaku taikei [NKBT]

[Survey of classical literature of Japan]

Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten

Two volumes (jō, ge)

Volume 1 [Jō], NKBT Volume 67, 1967

Volume 2 [Ge], NKBT Volume 68, 1965

Aston 1, Aston 2

Aston's translation was first published in two separate volumes by the Japan Society in 1896. The two volumes were republished in 1924 as a single volume in which the two earlier volumes were bound together with their original pagination. The 1972 Tuttle publication used here is a facsimile of the 1924 edition, which continues to be the most useful translation in English. It is remarkably reliable, but is best used together with the original text and other Japanese sources.

W.G. [William George] Aston (translator) [1841-1911]

Nihongi

(Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to AD 697)

Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1972

Volume I: iv, 407 pages

Paperback, two volumes in one

|

Emperor Tenmu's 684 kabane decree |

||

|

NKBT 68: 464-465 |

Structural translation |

Aston II: 364-365 |

|

~\ÈKñAÙHAXüV°©AìªFV©AȬVºäÝ©BêHAáÁlBñHA©bBOHAhHBlHAõ¡BÜHA¹tBZHAbBµHAABªHAâjuB¥úAçRöEHöE´öEO öEácöEïéöEOäöE¼öEâcöEHcöE§·öEðlöER¹öA\OA©HáÁlB |

13th year [of reign], Winter, 10th month, 1st day. [The emperor] decreed and said [proclaimed], "[We] again revise the clan titles (kabane °©) of the many families (uji ), create titles (kabane ©) of 8 colors [kinds] (yakusa ªF), and thereby blend [consolidate] (marokasu ¬) under Heaven the myriad titles (yorodzu no kabane äÝ©). The 1st [title] is called Mabito. The 2nd is called Asomi. The 3rd is called Sukune. The 4th is called Imiki. The 5th is called Michinoshi. The 6th is called Omi. The 7th is called Muraji. The 8th is called Inaki." On this day, Moriyama no Kimi, Michi no Kimi, Takahashi no Kimi, Mikuni no Kimi, Tagima no Kimi, Umaraki no Kimi, Tajiji no Kimi, Wina no Kimi, Sakata no Kimi, Hata no Kimi, Okinaga no Kimi, Sakahito no Kimi, Yamaji no Kimi, to [these] 13 families (uji) [the court] granted a title (kabane ©) and called [them] Mabito. |

Winter, 10th month, 1st day. The Emperor made a decree, saying:-- |

Selected wabon editions of Shinsen Shōjiroku

Many collations of legacy manuscript and print editions of Shinsen Shōjiroku were published during the Tokugawa period. Saeki Arikiyo describes known editions, some in great detail, and shows photographic images of several. In this section, I will introduce a few of the most prominent editions, based on Saeki's description. I will also show my tallies of editions held in libraries and archives as listed by CiNii.

|

Selected wabon editions of Shinsen Shōjiroku |

||

Shinsen Shōjiroku

1668 Shirai edition in NDL

Forthcoming

Shinsen Shōjiroku

1669 Matsushita edition in WUL

½e¤¼ (ï)

Vï©^´

Manta Shinnō et al. (compilation)

Shinsen Shōjiroku shō

[Newly compiled record of titles and families extracts]

Location and name of publisher not stated

182 numbered folios bound in one volume

Colophon (182a) states as follows.

ÈÑ°¶ãN / tO

Kiyū Kanbun 9-nen / Haru 3-gatsu

Earth-rooster 1669-04 Spring

¼õRl

Seihō Sanjin hashibumi

Seihō Sanjin preface

[→ Matsushita Kenrin 1637`1703]

¶³NëJ]VZ{æ謬ÖÊEZ

1818 copy and collation by Kojima Seisai (¬¬Ö c1797-1862) from collated book by Kariya Bōshi (ëJ]V 1775-1835), according to Waseda University Library description of this copy. Kojima Seisai, a calligrapher and Confucian scholar, was a retainer of the lord of Fukuyama domain in Bingo province (how part of Hiroshima prefecture). Kariya Bōshi, aka Kariya Ekisai (ëJ棭Ö), one of Kojima's teachers, was a collector and biliographer of old Chinese and Japanese texts, and a calligrapher. Kariya was born in Edo the son of a book dealer and a townsman by status.

The first page of this copy shows 5 owner seals as follows, across the top from right to left, then down the right from the middle to the bottom. The seals marked also appear on the colophon. Both seals appear together, and in the same positions relative to each other, in some other works in Waseda University Library. Both may belong to Gomi Kinpei.

ܡϽ

sVä½

R L

Îì

Gomi Kinpei (ܡϽ 1877-1924) was an Imperial Household Ministry (Kunaichō {àÈ) bureaucrat. Waseda University acquired his personal library after his death.

Shinsen Shōjiroku

CiNii listed copies

CiNii ("sigh-knee"(], a "Scholarly and Academic Information Navigator" database managed by National Institute of Informatics (Inter-University Research Institute Corporation / Research Organization of Information and Systems).Searching for publications attributed to äݽe¤ (Manta Shinnō) under books and magaines (}EGõ) on CiNii yields 36 items, which include the 34 items returned from author search (Òõ). The following chart shows a breakdown of the holdings of the 36 items, some held by more than one library, by edition (my tallies, based on data retrieved on 10 September 2019).

Early and middle Edo 3 volume 㺠editions 1668 Shirai 5 1669 Matsushita 2 1812 Shirai 3 Middle Edo 1 ----------------------- Holdings 11 Middle and late Edo 4 volume Ô¹ editions 1807/1818 Hashimoto 18 1834 Hashimoto 6 Late Edo 1 ----------------------- Holdings 25 Meiji Okajima Shinshichi 4 volume Ô¹ edition Vï©^ 1 Ô¹ ªáÁµ [¾¡NÔ] 1939 Koten Hozonkai edition 1939 Vï©^´^ 60 ÃTÛ¶ï 1983 Onko Gakkai edition Vï©^ 3 QÞ]Aæ448AG Gusho ruiju edition ·Ìwï Onko Gakkai <Onko-Academic-Society> Dedicated to preservation of wood blocks and other materials related to Gunsho ruiju and to studies of the work and its compiler Hanawa Hokiichi (·ÛÈê 1746-1821) Zoku Shōjiroku Vï©^ ã©^@ 1 [ÊÒs¾] Copiest uncertain [ÊNs¾] Year uncertain

Shinsen Shōjiroku

Yosha Bunko copy of

1807/1818 Hashimoto edition

Forthcoming

Áê®P Íà®ìºq o_¶Y º¡Eqå ä®mºq {´®Îºq {´®Vºq {´®Éª ªc®Ãµ üZ®ÉZ iy®lY Ú^ , æ1-10ª , æ11-20ª , æ21-30ªThe title page on the back of the cover of the 1st (Flowers) volume shows, below the title, ¹ø / Slû (Onbikidzuke / Zen-yon-satsu) -- "Pronunciations attached / Total 4 volumes". The "on'in" (¹ø) are attributed to "the late Motoori no Ushi" (Ì{ål). (Ibid.)

Hashimoto Inahiko (´{îF 1781-1809) was born in Aki province (Aki no kuni ÀåY AÀ|), aka Geishū (åYB), now the western part of Hiroshima prefecture. Hashimoto's names included Hojirō (ÛY) and Inazō (î ) among others, and his "shō" (©) was Minamoto (¹). Hashimoto became a student of Motoori Norinaga ({é· 1730-1801), a national studies scholar in Ise province (now part of Mie prefecture), in 1798. He was about 17 at the time, around 20 when Motoori died in 1801, and would die 8 years later in 1809, some 9 years before the publication of the SSSR edition attributed to his work in 1818.

The title page attributes the volumes to "The printing blocks of Yoshida Shōkondō" (Yoshida Shōkondō shi gc¼ª°²), an "Ōsaka bookshop" (Naniwa shoshi QØãæ), which both printed and sold the volumes. (Ibid.)

The preface -- "Teishau Shaujiroku no hashibumi" (eCVEVEWNmnVmu~) -- is dated and signed "1818 winter, Taira no Ōhira" (Bunshau no hajime no toshi no fuyu, Taira no Ohohira ¶³N~½½å½). Note that both ³ and are marked to be read "shau" (shō) rather than "sei" in this edition. (Saeki 1:82)

Taira no Ōhira (½½å½) is otherwise known as Motoori Ōhira ({å½ 1756-1833), was born the first son of an Ise province townsman Inagaki Munetaka (î²), aka Inagaki (î_), original name ({©) Yamaguchi (Rû). The first son became a student of Motoori Norinaga ({é· 1730-1801) around 1769 when about 13 years old, and Motoori adopted him in 1799 when he was about 43. This was the year after Hashimoto Inahiko became a student of Motoori Norinaga, and two years before Motoori Norinaga died, leaving Motori Ōhira as his successor and thus mentor of the young Hashimoto. Motoori Ōhira aka Taira no Ōhira had probably been mentoring his younger fellow "gate desciple" (montei åí) from the time Hashimoto was accepted as a student in the Motoori school. Morimoto Norinaga's natural son, Motoori Haruniwa ({të 1763-1828), N1213ú had lost his sight by 1795, when he was around 32, hence the need to adopt a successor. Motoori Ōhira signed with various names, including Fuji no Kakitsu (¡_à).

The colophon is dated wood-hare fall, 1808-8/9 (Bunka 4-nen teibō aki shichigatsu ¶»lNKHµ) and bears the following attributions. (Saeki 1:89, but my readings, romanizations, and [bracketed] remarks)

ÀåY@¹îFÞZ

Aki [province] [now part of Hiroshima prefecture]

Minamoto no Inahiko kinkō [careful corrections]

→ Hashimoto Inahiko (´{îF 1781-1809)

ɨ@¡·Nâ³

Ise [province] [now part of Mie prefecture]

Fuji no Nagatoshi hosei [supplementary revisions]

[→ Motoori Ōhira ({å½ 1756-1833)]

Copy 1 of Hashimoto edition

The Hashimoto edition consists of four separately bound volumes (satsu û) with flower-bird-wind-moon (Ô¹) title. This copy was purchased from an antiquarian book dealer in Ueda city in Nagano prefectue. The book was descibed a published in Bunka 4-7 (1807) by Izumidera Monjirō (o_¶Y) and others (see below).

Publishers and sellers

The colophon lists 12 people who publishers (hakkō á¢s) and/or booksellers (shoshi ãæ), beginning with µOÊ¡®¬@o_¶Y Miyako Sanjōdōri Masuyachō Izumoji Bunjirō

µ was an alternative way of writing hence µs for s (Kyōto). The graph also has a history of use in early representations of (Tōkyō) as µ. Tokyo was commonly written (Tokyo, Tokei) was commonly written µ (Tokei, Tokyo) until about the middle of the Meiji period. The character is considered a popular alternative of though careful writers would graphically differentiate them. The Sino-Japanese Go (Wu = pre-Tang), Kan (Han = Tang, Chang'an), and To (Tang = Song, Yuan, Ming, Yuan, Qing) readings of both characters were kyō (kiyou, kiyau), kei, and kin. See Tōkyō Nichinichi Shinbun banners and other examples and details on the New Nishikie website.

Masuyachō (¡®¬) is today's Masuyachō (®¬).

Among the 12 listed publishers and sellers, 2 were in Miyako (µ) [Kyōto µs, s), 4 in Edo (]Ë), 2 in Nagoya (¼Ã®) in Bishū (öB) [Owari no kuni ö£], 1 in Wakayama in Kishū (IB) [Kii no kuni IÉ], and 2 in Ōsaka (åâ). Note that the list begins in Kyō, jumps to Nihonbashi in Edo, then continues southwest back to Ōsaka in the Kinki area.

Volume 1 Ô Flowers

0a Cover

ù³ / Vï©^ / Ô

Teishau Shaujiroku / Ka (Hana)

Teishō Shōjiroku / Flowers

0b Title, pubisher, promotion

Title

@ ù³ / Vï©^ // ¹ø / Slû

Teishau Shaujiroku //

Onbikidzuke (On'indzuke) /

Zen 4-satsu

Teishō Shōjiroku

Pronunciations attached

Total 4 volumes

Publisher

QØãæ / gc¼ª°²

Naniwa shoshi / Yoshida Shōkondō shi

Nainwa (Ōsaka) bookstore

Yoshida Shōkondō wood blocks (printer)

Publicity

}¹øÆ¢Ón©^ÌÚÀɵÄ

Ì{ålÌïѨ©êµÈè

@ Somosomo kono on'in to ifu ha Shaujiroku no

mokuan ni shite ko Motoori no Ushi no

erabiokareshi tokoro nari

As for the pronunciations,

they are where (as, according to how)

[they] were chosen and put (left) [by]

the late Motoori no Ushi as a guide

of (to, for reading) Shōjiroku.

1a-2b ù³Vï©^

Teishau Shaujiroku no hashibumi

Preface ot (to) Teishō Shōjiroku

1a-3a ãVï©^\

@@@

1a-14b ©^Ú^@Ü\¹ø

@@@ Shōjiroku mokukoku Gojōon-biki

1a-10b ©^ðZ ½éåÞË

Shōjiroku wo yomikamugahetaru oomune

Main points of having read and rectified Shōjiroku

(See the note, below, on

"Etymology of Z ½é")

Volume 2 ¹ Birds

0a Cover

ù³ / Vï©^ / ¹

Teishau Shaujiroku / Chō (Tori)

Teishō Shōjiroku / Birds

Volume 3 Wind

0a Cover

ù³ / Vï©^ /

Teishau Shaujiroku / Kaze

Teishō Shōjiroku / Wind

Volume 4 Moon

0a Cover

ù³ / Vï©^ /

Teishau Shaujiroku / Tsuki

Teishō Shōjiroku / Moon

Etymology of Z ½é

The editors of the text read Z½é as "yomikamugahetaru" (~JKw½é). This represents early speech before "-mu-" shifted to "-n-", and "he" represents older kana orthography before "ha-gyō" shifted to "a-gyō" in such words.

The entry on "kamugahe" (©ÞªEÖ) yÖA¨ÖAlÖzin Iwanami kogo jiten (âgÃê«T) presents it as the precursor of present-day "kangae" (©ñª¦). The entry (page 332) avers that "kamugahe" originates from "ka" (J) meaning "place" or "point", plus "mukahe" (Jw) meaning the bringing of two things together (in opposition) -- in other words, to compare two things, and study their acceptibility, and correct them. The primary meaning is given as "to study the veracity (truth or falsehood) of something, and correct it" (Ì^Uð²×A½¾·). of something and " (mukau) [face, oppose]".

Based on the information in the entry, "kangaeru" originated from "kamukaheru" as follows (Ono et al 1974, 1977: 332).

> "kamukafu" > "kamugafu"

> "kangafu" (kangau), "kangaheru" (kangaeru)

Hence yomi + kangaeru + te aru (taru)

>"yomikangaete aru" > "yomikangaetaru"

.

Meaning "reading and considering correctness",

"rectifying", "recensioning", "collating"

åìWA²|ºLAOcàÜY (ÒÒ)

âgÃê«T

FâgX

1974N1225ú æPüs

1977N720ú æSüs

16 (A}á)A1488({¶) y[WA

Ōno Susumu, Satake Aki, Maeda Kingo, editors

Iwanami Kogo jiten

Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten

1974-12-25 1st printing published

1977-07-20 4th printing published

16 (preface, guide), 1488 (entries) pages

Soft cover, boxed

Copy 2 of Hashimoto edition

ù³@Vï©^@¹øt@SSûiÔ¹jE¶»lNEt

ù³@Vï©^@¹øt@SSûiÔ¹jE¶»lNEt ¶»lN@À|@¹îFZ@ɨ@¡·Nâ³ VÛÜN@QØÑ@ÁêJP Å oNÌÉÍÇDÈóÔÅ·BàeÍÊ^ð²QÆè¢Ü·B

Shinsen Shōjiroku

Yosha Bunko copy of

Kosugi 1876 edition of

Shirai 1668 edition

This edition, which is similar to the Kosugi 1876 edition described by Shirai Arikiyo (see below), was first of two wabon editions of Shinsen Shōjiroku I bought in 2019. The second was the 1807/1818 Hashimoto edition (above).

I bought the edition shown to the right from a Yahoo! Auction seller that specialized in both electronic and paper editions of older texts. The seller gave little information about the book other than to show images of the cover and colophon with the following general description.

]Ëa{Vï©^i°¶8NÂãój ä@ö ©È¬P_ °¶8N{ ]Ëúħ ãcKºq n

y»^zå{3ª1ûBc259®B

Large book. 3 books bound in 1 volume. Vertical 259 millimeters.

yìÒz½e¤Ù©ÒB¹îFZB¡·NâBä@öi©È¬jP_B

Compiled by Manta Shinnō and others.

Corrected by Minamoto no Inahiko. Supplemented by Fuji no Nagatoshi.

Yamato readings by Shirai Sōin (Jishōken)

yNãzOm6N¬§B°¶8N4Aä@öi©È¬jæëE§B ]ËúħBmåãnãcKºqÂB

yõlzªÞunvBÆEàÌ1182ðAܸo©ÉæÁÄcÊ335E_Ê404E×326ÉåʵA¢ŻÌeð{ÑÉæÁĶEEERéEÛÃEåaEÍàEaòÌÉñµAÅãÉ¢èG©117ðY¦éB»¶Ì{ÅÍÙÆñǪȪ³êA¼ÌÉU©·éí¶ârÆ{ÌêΩbƧåÆÌ2©ç´`ªè³ê鷬Ȣiuú{ÃT¶wå«TvQÆjB

üiàÆ3ª{ð1ûÉ{jEèâÓtEóÔÇDi\ââÉÝjBL¼E ó èB

The seller stated that the book was a "middle-Edo republication" but Minamoto no Inahiko completed his edition, with the help of Fuji no Nagatoshi, in 1807, and it was published in 1818 -- which was late Edo. This, according to Saeki, was the Hashimoto Inahiko edition, but images of this edition looked nothing the Yahoo! Auction offering. The design of pages of the offering resembled those of an 1876 edtion Saeki attributed to Kosugi Onson (Sugimura), which was early Meiji. However, even if the condition of the cover had been rattier, the price was good, so I bought it.

Having collected several hundred mid-19th century woodblock prints, and a number of late Tokugawa and early Meiji wabon publications, I was familiar with the manner in which publishers reproduced earlier works, copying their colophons as received, sometimes but not always adding their own colophons. So I was prepared for anything. It would be worth it just to have such a wabon in my hands.

Size

The book measures 26 x 18 x 3 centimeters tall, wide, and thick. The dimentions are those of the standard "large book" (Ōbon å{), which corresponds to today's B5 standard widely used for weekly magazines.

Cover

The title slip on the front cover reads like this.

Vï©^

㺠/ {

10 (\A)A167 ({¶)A2 ( t)

Shinsen Shōjiroku

[Newly compiled record of titles and families]

Jō-Chū-Ge / Gappon

[Upper-Middle-Lower (books) / Bound (as one) book]

10 folio (memorial, preface), 167 folio (main text),

2 folio (colophon) [total 179 folio, 358 pages]

Compilers

The first words in the memorial (\) are bäݽ referring to Manta Shinnō (äݽe¤ 788-830) and the others who compiled Shinsen Shōjiroku. b is read }N (makura), which marks the "head" of the memorial, which "reports" the completion of the work to the emperor. Manda, an imperial prince, holds a position in the Central Affairs Office (Naka-tsukasa-kyō ±¨), which later became Central Affairs Ministry (Naka-tsukasa-shō), the precursor of the Imperial Household Ministry (Kuanishō {àÈ) created in the Meiji period, which became the Imperial Household Agency (Kunaichō {à¡) from 1947. Manda and the others credited with the compilation are listed by court rank and name at the end of the foreword, which is dated Kōnin 6 (815), but had been completed and presented to the emperor the year before (see below).

Short title

The short title ©^ (Shōjiroku) appears on the upper part of the fold of all folios except the two unnumbered folios in the back.

Contents

The book consists of 179 folios or 358 pages. All but the last 2 folios (4 pages) are numbered. The folios of the main text, including the publisher's corrections, are numbered apart from preceding and following parts, as follows.

1-3 \ -- Dated and signed foreword by compilers 7-10 -- Unsigned preface 1-165a Text proper 165b-167b Corrections by publisher Ueda Uhewe (Uhee) [1] Dated and signed afterword by editor Shirai Soōin [1] Publisher's address and name and seller's catalog

Pagination of main text

The main text consists of 167 numbered folios.

Multiples (m) of 10 (\) are always m10 (m\) -- e.g., 20 ñ\), 30 (O\), 120 (Sñ\) -- except 29 (Oã), 31 (¿ê), and 32 (¿ñ).Introductory memorial (\) states that the compilation includes 1,182 families (uji ) in 31 books (kan ª) (2b), but the preface () says it includes 1,182 families in 30 books divided into 3 parts (bu ) (10a-10b).

Ordinarily, the first page of a book begins with the book number. In SSSR, however, book numbers come at the end of each book, preceded by "right" (migi E), which signifies that the book thus numbered appears to the right. Hence Book 1, though beginning from Folio 1a of the text proper, is numbered on Folio 5a, where Book 1 ends and Book 2 begins. The number for Book 30 appears on Folio 165a at, the very end of the text proper, and is followed by a line stating that this is the end of the SSSR books.

1a-4b, g4ab (ê`l), +4ab (ãl) æêã Dai-1-chitsu 1st folder

5a Eæêª Right book 1

12a Eæñª Right book 2

19b EæOª Right book 3

24b Eælª Right book 4

32b Eæܪ Right book 4

35a EæZª Right book 6

38a E浪 Right book 7

41b E檪 Right book 8

48b Eæ㪠Right book 9

52b Eæ\ª Right book 10

53a V{ Middle book

æñ Dai-2-chō 2nd quire

58b Eæ\êª Right book 11

62a Eæ\ñª Right book 12

65b Eæ\Oª Right book 13

70b Eæ\lª Right book 14

74b Eæ\ܪ Right book 15

80b Eæ\ (}}) Right book 16

87b Eæ\µª Right book 17

93a Eæ\ªª Right book 18

99a ºV{ Lower book

101a Eæ\㪠Right book 19

108b Eæñ\ª Right book 20

æOã Dai-3-chitsu 3rd folder

113b Eæñ\êª Right book 21

118b Eæñ\ñª Right book 22

123a Eæñ\Oª Right book 23

130b Eæñ\lª Right book 24

134b Eæñ\ܪ Right book 25

137b Eæñ\Zª Right book 26

142b Eæñ\µª Right book 27

158a Eæñ\ªª Right book 27

150b Eæñ\㪠Right book 28

165a EæO\ª Right book 30

Vï©^ªI

Shinsen Shōjiroku books end

165b ãcKºqJZ

Ueda Uhewe (Uhee) unfolds corrections

Colophon

The colophon consists of an unnumbered folio, which I will call 168 because it follows folio 167, the last pages of the main text. The front side (168a) is an afterword by the person who dates, signs, and seals it on the back side (168b), as follows.

Date and editor's name and seal

°¶ú\ÄVÐ

P_ ©È¬@ö Þæë

ó? ä?

Kanbun boshin natsu no hajime

[Kanbun 8 (1668) beginning of summer]

<Kunten> Jishōken Sōin

<In> Shirai-shi

[<Yamato translation markup> (by) Jishōken Sōin]

[<Seal> Shirai family]

Printer and seller

QØãæASâV´klAãcKºq

Naniwa Shoshi, Shinsaibashi Kitadzume, Ueda Uhewe (Uhee)

[Naniwa (Ōsaka) book shop, published by Ueda Uhee of Shinsaibashi on northside (Kitadzume)(of Ōsaka castle)]

@ªVñ@¶cÊãl\ñ

@ªVO@¶cʺO\ñ

@ªVl@EcÊãO\O

@ªVÜ@EcʺO\lARécÊñ\l

@ªVZ@åacÊ\ªAÛÃcÊñ\ã

@ªVµ@ÍàcÊl\ZAaòcÊO\O

@ªVª@æñã@¶_ÊãO\ª

@ªVã@¶_Êñ\O

@ªV\@¶_ʺñ\ê

@ªV\ê@E_ÊãO\Z

@ªV\ñ@E_ʺñ\ã

@ªV\O@Ré_Êl\Ü

@ªV\l@åa_Êl\l

@ªV\Ü@ÛÃ_Êl\Ü

@ªV\Z@Íà_ÊZ\O

@ªV\µ@aò_ÊZ\

@ªV\ª@æOã@¶×ãO\ÜA¶×ºO\µ

@ªV\ã@E×ãO\ãAE׺Z\ñ

@ªVñ\@Ré×ñ\ñAåa×ñ\ZAÛÃ×ñ\ãA

@@@@@@Íà×Ü\ZAaò×ñ\

@ªVñ\ê@¢èG©S\µ

@Vï©^lØââAVï©^í¶AVï©^©õø

Owner seals on Yosha Bunko copy of

Owner seals on Yosha Bunko copy ofKosugi 1876 / Shirai 1668 edition of Shinsen Shōjiroku Yoshi Bunko scan |

Provenance and owner seals

Owners of wabon often impressed their seals on the first pages of each bound section of a book to identify it as theirs. Wabon passed down through generations of owners are likely to accumulate a lot of seals.

My copy of the Kosugi 1876 / Shirai 1668 collation of Shinsen Shōjiroku bears three owner seals on the first page of each of the three volumes (ãº) that have been found together to make the gappon ({) edition, as follows.

Square seal at top

My thanks to Kunioki Yanagishita for help reading this.

Í

Kawai zōsho

Kawai library

Square seal in middle

ß

𫟯

Chikashige zōsho

Chikashige library

𫟯 (nabebuta ³ plus sato ¢) is for d.

3. Small circular seal kì Kitagawa 4. Large square seal with flat corners Title slip Vï©^ 㺠{ Shinsen Shōjiroku jōchūge gappon Inside front cover SÜ\ ¢èG© Hyaku-go-jū-chō-ura yori Mitei zasshō "Undetermined miscellaneous kabane" from back (reverse) of folio 150 Front matter 1-10 (10 folios) Vï©^ãV{ 1-52 (52 folios) Vï©^V{ 53-98 (46 folios) Vï©^ºV{ 99-167 (69 folios) Back matter 2 unnumbered folios 1a publisher's credits. 1b date of source Notations by owners 2a Catalog of publications 2b Blank Catalog of publications ð òÚ^ Lists 17 titles 10th title Vï«^ (}}) äݽe¤ / «¼mNL (}}) Oû QØãæ SâV´kl ãcKºq Colophon °¶ú\ÄVÐ ©È¬@ö Þæë [P_] Negative carved (A) [white on black] carved seal (ó) reads "Shirai shi" (ä) Seal refers to Shirai Sōin (ä@ö), a national studies (kokugaku w) scholar during the early Tokugawa period (1600-1868). Shirai, a doctor, was active in Ōsaka (åâ) during the Kanbun (°¶ 1661-1673) and Enpō (ó 1673-1681) eras. He advocated Shintō-Confucian syncretism (_òêv) and criticized Buddhist teachings (§³) and Daoist teachings (¹³). He added kunten (P_) [marks from reading Chinese in Japanese] to the Shinsen Shōjiroku and was the first to publish [an edition with kunten]. His gō () [names adopted by authors and artists] were Hakuun Sanjin (_Ul) and Jishōken (©È¬). ãcKºq, °¶8 [1668] æë Kanbun boshin natsu no hajime Kanbun 8 (1668) beginning of summer Kanbun 8 12 February 1668 - 21 January 1669 NOTE (Kitagawa's hand?) ú\nªVNiåãnì³Vcç N¾¡µ\NÇñS\µNç Boshin wa hachi no toshi nari Shujō [Ue, Kami] wa Reigen Tennō naru. Boshin is the 8th year [of Kanbun]. The Lord High is Reigen Tennō. From this year Meiji-17 is 217 years later. Reigen (1654-1732, r1663-1687) reigned for 24 years, during which there were a number of calamaties including a fire that ravaged Edo in 1668, a rebellion of Ezo natives against their Matsumae domain suzerains in 1669-1672 suppressed with the help of forces dispatched by the Tokugawa government, and a Tokugawa government expedition to explore what were then called Buninjima (³l Mujintō) -- "islands with no people" -- which inspired the English name "Bonin Islans" -- referring to what later were peopled by Japanese and non-Japanese, claimed by Japan, and named Ogasawara guntō (¬}´Q) or Ogawawara Islands. Red brushed note ¾¡\µNÜåâV âVªªF Meiji 17-nen 5-gatsu Ōsaka Motoyuki Inbe [Imibe, Imube, Saibe] Yashiohiko May 1885 At Ūsaka Motoyuki Inbe Yashiohito Black brushed note å³ON\ñú@åâs½À\ê¬ lÚSO\µÔ®~Ñcõ (kì) ÄCyçß ßdªªFOO¼(åãTi@)/p277 ¯ñ æêªÜZåj ¾¡ñ\ñNªñ\ªúi jú) ñµµ ààVnRÙ»· Kanazawa Shishin Saibansho Kanazawa First Instance Court 13 September 1876 Established as Kanazawa Court (Kanazawa Saibansho àòÙ») 1 January 1882 Became Kanazawa First Instance Court 1 October 1890 Renamed Kanazawa District Court (Kanazawa Chihō Saibansho (àònûÙ») ßdªªF ßdªªF({àÈ) ¯ñ ælZªãåj ¾¡O\ñNññ\êú öÝÄCyçß ñ㪠(µ) ÞE»]ÜÊMÜ ßdªªF mãpm°ßdªªF Main text 1,182 uji in 31 volumes Front matter Folio 4 Vï©^ OmZNµñ\ú 1 September 815 Gregorian 28 September 815 Julius ¾¡\µNÇêçµ\Ngiç 1,070 years from Meiji 17 (1885) Folio 1 beginning Volume 1 Square unread double border seal with flat corners in bottom right corner of 1a. Unread note in vermillion in right margin above seal blacked out. Vï©^ @æê ¶cÊ Folio 53 beginning Volume 2 Vï©^V{ @æñ ¶_ÊãStudies

Shinsen Shōjiroku ranks high among students of Japan's sociopolitical history as a window into the manner in which, by the start of the 9th century, titled "families" (uji ) or "clans" (shizoku °) were being classified according to whether they originated from imperial family blood lines, other domestic blood lines, or Chinese or Korean blood lines. Why this should be a concern, at the time Shinsen Shōjiroku . gods"who was who, where"separate titled families by the tracked in what amount to census-style genealogical records. Some researchers have focused on the manner in which the records were used to clea

Since Miller 1974 (above), a number of articles and books in English have touched upon Shinsen Shōjiroku social historians asSince Miller 1974 (above), a number of articles and books in English have touched upon Shinsen Shōjiroku in more than a casual manner.

Meiji period

Kurita Hiroshi's SSSR studies

Forthcoming

1950s-1990s

Saeki Arikiyo's SSSR studies

The foremost student and reporter on Shinsen Shōjiroku in the 20th century was

As a specialist in early Japanese history, Saeki Arikiyo (²L´ 1925-2005) covered a lot of ground but is best known for his studies and recensions of Shinsen Shōjiroku. He began his work in the 1950s, after the Pacific War. By the early 1960s he had published the first 2 volumes of what would be 10-volume. The initial volume presented the text of the 1812 edition that Saeki adopted as the "base book" (teihon ê{) for his study (see below), with headnotes showing differences in other texts and recensions. The second volume presented his overview of the life of the work over the centuries, including other editions and previous research by other scholars.

From 1981 to 1983, Saeki published 6 more volumes, devoted to commentary on each of the records in light of what was known from other sources about the individuals they describe. In 1984 he published a 9th volume consisting of an index to the 8 volumes and additional commentary. And in 2001 he published a 10th volume of "gleanings" reflecting information and thoughts he had gathered since his earlier work. The first 9 volumes became available in OD (on-demand) editions in 2007 and 2008. The final 10th volume became available through OD in 2018.

I have the first 8 volumes in early non-OD editions.

Saeki 1962-2000

²L´

Vï©^̤

FgìO¶Ù

Saeki Arikiyo

Shinsen Shōjiroku no kenkyū

[ Studies of Shinsen Shōjiroku ]

Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kobunkan, 1962-2008

10 volumes, hardcover, boxed

The volumes are not numbered. I have assigned them numbers to facilitate citing them -- Saeki 1, Saeki 2 and such.

I have only the first 8 volumes. The particulars shown for Volumes 9 and 10 have not been directly confirmed.

Saeki 1 -- Basic text

{¶Ñ

ºaO\µNµêú Ås

ºal\êNOêú ÄÅs

Basic text

1962-07-01 1st edition [1st printing] published

1966-03-01 Reedition [Reprinting] published

4 (plates), 9 (preface, contents),

399 (main text and SSSR index),

7 (subject index)

Saeki 2 -- Research

¤Ñ

ºaO\ªNl\Üú Ås

ºal\ZNlñ\ú OÅs

Research

1963-04-15 1st edition [1st printing] published

1971-04-20 3rd edition [3rd printing] published

4 (plates), 11 (preface, contents),

543 (main text), 31 (index)

Saeki 3 -- Investigations 1

læÑ æê _Aª1-2

ºaÜ\ZN\ñ\ú æêüs

ºaZ\ONµ\ú æñüs

Investigations 1 Preface, Books 1-2

1981-12-10 1st printing published

1988-07-10 2nd printing published

6 (plates), 9 (preface, guide, contents),

472 (main text),6 (index)

Saeki 4 -- Investigations 2

læÑ æñ ª3-10

ºaÜ\µNññ\ªú óü

ºaÜ\µNO\ú s

Investigations 2 Books 3-10

1982-02-28 printed

1982-03-10 published

6 (preface, guide, contents), 511 (main text)

Saeki 5 -- Investigations 3

læÑ æO ª11-16

ºaÜ\µNµêú óü

ºaZ\µNµ\ú s

Investigations 3 Books 11-16

1982-07-01 printed

1982-07-10 published

7 (preface, guide, contents), 476 (main text)

Saeki 6 -- Investigations 4

læÑ æl ª17-21

ºaÜ\µN\ê\ú óü

ºaÜ\µN\êñ\ú s

Investigations 4 Books 17-21

1982-11-10 printed

1982-11-20 published

7 (preface, guide, contents), 476 (main text)

Saeki 7 -- Investigations 5

læÑ æÜ ª22-28

ºaÜ\ªNÜêú óü

ºaÜ\ªNÜ\ú s

Investigations 5 Preface, Books 22-28

1983-05-01 printed

1983-05-10 published

6 (preface, guide, contents), 482 (main text)

Saeki 8 -- Investigations 6

læÑ æZ ª29-30, í¶Aââ

ºaÜ\ªNªêú óü

ºaÜ\ªNª\ú s

Investigations 6 Books 29-30

Itsubun [Fragmental texts], Hoi [Addenda]

1983-08-01 printed

1983-08-10 published

4 (plates), 9 (preface, guide, contents),

394 (main text), 7 (index)

Saeki 9 -- Index, commentary

õøE_lÑ

Sakuin, arguments and considerations compilation]

1984-03, 458 pages

Saeki 10 -- Gleanings

EâÑ

Shūi hen

[Gatherings and leavings (Gleanings)] compilation

2001-08-01, 384 pages

In this final volume, Saeki examines manuscript copies of Shinsen Shōjiroku texts representing the two oldest lineages of texts, which he calls the "Kenmu 2-nen kei" (ñNn) or "1335 related" and "Enbun 5-nen kei" (¶ÜNn) or "1360 related" texts. It includes several short reports concerning the genealogies of some of the families recorded in the peerage. In this connection Saeki demonstrates that the correct name of the wÞ (Sena) family of Kōkuri (åí Koguryō) origin was actually ÑÞ (Sena).

The Sena family is said to have descended from the 19th-generation Kōkuri (åí Koguryō) king Kwanggaet'o (J Kōkaido AJy). The family originated in Yamato with the asylum of Sena no Fukutoku (wÞ¿ bd ukn 7th century), a 7th-generation descendant of King Kwanggaet'o. Fukutoku was first titled Kimi (ö) and later became Konikishi (¤). His grandson, Takakura no Fukushin (qM 709-789), recieved the title Koma no Asomi (í©b), aka Takakura no Asomi (q©b). The peninsular origins of a number of families in the Shinsen Shōjiroku were similarly evident in their family names.

"Basic" and "secondary" texts

Saeki Arikiyo adopted as his "basic text" (teihon ê{) the Mikanagi Kiyonao edition (äÞ´¼{) of Shinsen Shōjiroku (Vï©^) in the Jingū Bunko (_{¶É) at Ise Jingū in Mie prefecture (Saeki 1:137). Mikanagi Kiyonao (1812-1894), a late Edo-period and Meiji-period national studies (kokugaku w) scholar, was a kannushi (priest) at Ise Shrine. (Saeki 1:137)

Saeki took as an "accessory text" (fukuhon {) the Yanagiwara Norimitsu edition (ö´Iõ{) of Shinsen Shōjiroku shō (Vï©^´) in Iwase Bunko (⣶É) in Nishio city in Aichi prefecture (Saeki 1:137). Yanagiwara Norimitsu (ö´ Iõ 1746-1899 Motomitsu) was a late middle Edo-era court official and historian.

According to Saeki, these "basic" (Shōjiroku) and "accessory" (Shōjiroku shō) editions represent lines of descent from respectively a 1335 (Kenmu 2-nen ñN) text from the end of the Kamakura period, and a 1360 (Enbun 5-nen ¶ÜN) from the start of the Nanboku-chō era of the Muromachi period (Saeki 1:137).

The Kikutei Bunko edition (eà¶É{) in Kyoto University Library reflects the 1335 (Kenmu 2-nen ñN) text. The Kikutei family was originally the Imadegawa family, which goes back to the late Kamakura and early Nanboku-chō periods in the late 13th and early 14th centuries. The Hayashi Dokkōsai edition (ÑÇkÖ{) is based on the 1360 (Enbun 5-nen ¶ÜN) text. Hayashi Dokkōsai (1624-1661) was an early Edo-era neo-Confucian scholar. He was the 4th son of Hayashi Razan (Ñ R 1583-1657), a leading neo-Confusian scholar scholar of his generation.

My wabon edition

My wabon edition resembles the "Kosugi Onson transcription collated book" (Kosugi Onson tōsha kōgō hon ¬Ãçµ£Z{) -- judging from images and descriptions in Saeki (Saeki 1: images 15 and 16 in plates, descriptions on pages 122-123). Kosugi Onson, or Kosugi Sugimura (¬Ãçµ 1835-1910), was a late-Edo, Meiji-era national studies scholar from Awa province (Awa no kuni ¢g) in present-day Tokushima prefecture.

The Kosugi book, an 1876 (Meiji 9) transcription and collation, is in the possession of Iwase Bunko. A "collated book" (kōgō [kyōgō] hon Z{) is made by combining two or more volumes and binding them together in a single volume called a "gappon" ({) or "combined book". The title slip on the cover of my copy describes it as a "gappon" of three "jōchūge" (ãº) or "top, middle, and bottom" volumes.

As described by Saeki, the Kosugi book is a collation of the 1668 Shirai Sōin edition (ä@ö{) of Shinsen Shōjiroku, as is my copy. The Shirai edition is the first version known to have been marked for reading in Japanese (kundoku PÇ), by Shirai, a doctor-cum-national studies scholar active in Ōsaka (åâ) circa 1661-1681, where his edition was published.

Saeki states that Kosugi's collation consists of the 3 volumes or (ãº) of the Shirai book, in with "transcriptions" (tōsha £Ê) of the "Naitō Hirosaki collation book" (Naitō Hirosaki kōgō hon à¡AOZ{), which Saeki says was collated between 1844 (Tenpo 15) and 1849 (Kaei 2) (Saeki 1:116). Naitō Hirosaki (à¡AO 1791-1866 à¡LO) was a late-Edo-era national studies scholar. Apparently his library was lost when his son, who was supposed to succeed him, failed, and the Naitō house became insolvent.

Saeki states that the whereabouts of the Naitō collation is unknown. What he knows about it, he knows through what Kosugi has transcribed in the back of his collated book, from the Naitō collation. Whether Naito's library was still around in 1876, a decade after Naito's death when Kosugi completed his collation, or whether Naito's collation fell into Kosugi's hands and was later lost, is not clear.

Saeki shows two images from the Kosugi collation, the first of the very first page of the collation, showing the names and ranks of the Shinsen Shōjiroku compilers, and the last page of main body of the text, showing the last records of the peerage. The corresponding pages of my copy are identical to these (Kosugi 1: Imges 15 and 15 in plates). The considerable blank space on the last page is filled with a long transcription in Kosugi's hand, of what appears to be information he found in Naitō's collated book. Saeki transcribes Kosugi's transcription in its entirely (Saeki 1:116-117).

In the transcription, Naitō -- who signed his name "Hirosaki" (AO) -- describes in great detail the collated books he borrowed between 1844 and 1849 to make his collation. Details include the names of the owners, and dates and other information from colophons. The transcription, in other words, explains how Naitō went about gathering available copies to in order to make his own collated copy.

The information in the transcription identifies one of the sources of Naitōs collation as a 1335 (Kenmu 2-2-7) ñNJµú) collation by "former Interior Minister Yoshida" (gcOà{), referring to Yoshida Sadafusa (gcè[ 1274-1338). Yoshida served as the Interior Minister from 1334-10-15 (Kenmu 1-9-9) to 1335-3-19 (Kenmu 2-2-16), which suggests that he was not yet "former" as of the date recorded in Kosugi's transcription from Naitō's collation.

As noted above, Saeki establishes two major "lineages" of texts descending from the original Shinsen Shōjiroku -- one the 1335 "Kenmu 2 line" (ñNn), the other the 1360 "Enbun 5 line" (¶ÜNn). He maps the many texts that have come down since in an elaborate "gengealogical chart" that spans all of 3 pages.

The line of descent of my wabon copy appears to be as follows, based on Saeki's placement of the Naitō and Kosugi collations (Saeki 1:126-128).

´{

Original book

´^´{ (ñNn)

Extract records (Kenmu 2-nen kei) [1335]

gcè[{

Yoshida Sadafusa [1274-1338] book

ä@ö{

Shirai Sōin book [1638]

{é·Z{

Motoori Norinaga [1730-1801] collation book

à¡AOZ{

Naitō Hirosaki collation book [1844-1849]

¬ÃçµZ{

Kosugi Sugimura collation book [1876]

The above lineage follows the most direct and prominent lines on Saeki's two family trees -- the second (Saeki 1:128) a more detailed elaboration of the part of the first (Ibid. 126-127) that concerns especially descendants of the early-Edo Shirai Sōin edition. I have not shown the many "collateral" texts that feed into or branch off the main line. Saeki came up with his "genealogy" with the help of charts showing representations of selected terms in 7 texts, including the 1335 and 1360 variations of the "original book" and the Shirai book (Shirai 1:72-76). The charts, in effect, compare the "graphic DNA" of the selected editions, in terms of the presence and absence of characters or differences in their styles.

Shirai edition

Saeki begins his chapter on printed editions of SSSR with Shirai Sōin's 1668 "kundoku" (PÇ) edition -- the first known eduction to mark the kanbun text for reading in Japanese. It consisted of 3 volumes (ãº) and measured 26.2 by 18.1 centimeters (W), essentially the same dimensions as my wabon version. (Saeki 1:78-79)

The size is that of a "large book" (ōhon å{ 27cm~18cm), which was probably the most common size of wabon. Its folios consisted of sheets of minoban (üZ» minnishiban üZ») paper (27cm~39cm) folded in two. This size of wabon compares with today's B5 (257mm~182mm) standard, commonly used for weekly magazines. A "medium book" (chūhon { 18-19cm~12-13cm), half the size of a "large book", was commonly used for more popular works, including illustrated stories of the "kusazōshi" (o) or "gesaku" (Yì) kind. The size is comparable to today's B6 (182mm~128mm) standard. A "small book" (kohon ¬{ 15-16cm~10-11cm), comparable to today's compact "bunko" (¶É) size, was used for a variety of genres, including commical "sharebon" ({) stories set in the pleasure quarters.

The afterword, date, and signature and seal are identical to those in my version. The afterword in my version, unlike the front matter and main text, which are marked for reading, is unmarked. Saeki's shows the afterword both puntuated and marked -- presumably his doing.

Matsushita book

In 1669, the year after Shirai's edition came out, Matsushita Kenrin (¼º©Ñ 1637-1704) published Shinsen ©^´. Saeki describes it as a stitch-bound-folio (ÜÔ) work in one volume measuring 15.7 by 10.4 centimeters, which corresponds to a "small book" (see above). Matsushita was a neo-Confucian-cum national studies scholar who, like Shirai, made a living as a doctor. (Saeki 1:79-80)

Saeki remarks that Matsushita's book was strongly influenced by Shirai's book (Shirai 1:90). RESUME

Gunsho ruiju edition

The 3rd printed edition of SSSR in Saeki's list is the 3-volume (ãº) version published as Book 448 (ªælSl\ª) of Gunsho ruiju (QÞ]), a collection of some 1273 books published beween 1793 and 1819. Saeki dates the KSRJ edition of SSSR to around the last year of the Bunka reign, which ended during its 15th year in 1818. He describes this edition as a wood-printed book measuring 26.5 by 18.1 centimeters -- i.e., a "large book" like that of the Shirai edition.

Shiraki views the GSRJ edition of SSSR as a descendant of several lines of texts that are ancestrally closer to the Kenmu-2 (1335) line than the Enbun-5 (1360) line, including the Shirai and Matsushita texts. Later metal-type editions of the GSRJ version of SSSR reflect later influences. (Saeki 1:80-81)

Hashimoto Inahiko edition

The 4th book in Saeki's list of printed editions is the Hashimoto Inahiko correction (´{îFZ) titled Teishō(Teisei) / Shinsen Shōjiroku (ù³ / Vï©^) or "Revised and corrected / Newly compiled record of titles and families". The date associated with the names of the two scholars credited for the corrections in the work is 1807-8/9 (Bunka 4-7) [Saeki erroneously writes êªZl (1804)]. But the work was published in 1818/9 (Bunsei 1) in 4 separately bound volumes titled Flowers (ka Ô), Birds (chō ¹), Wind (fū ), and Moon (getsu ). The volumes are 24.8 by 17.9 centimeters -- a smaller variation of a "large book". (Saeki 1:81)

1960s-1970sRichard Miller's 1974 SSSR studyRichard J. Miller Forthcoming |

2000s-2010s

Suzuki Masanobu's genealogy studies

Suzuki Masanobu (éسM b1977) specializes in early Japanese history, in particular the clan system (shizoku seido °§x) and regional control systems (chihō shihai seido nûxz§x). Suzuki received his doctorate in 2012 from Waseda University. The same year, he published his dissertation as Nihon kodai shizoku keifu no kiso-teki kenkyū (ú{Ãã°nÌîbI¤) [Basic research on Japan early-era clan genealogies] (Tōkyōdō Shuppan °oÅ). Since then, he has published a number of articles and books in Japanese and English.

Of particular interest to me are the following works.

Masanobu Suzuki

Methodology for Analyzing the Genealogy of Ancient Japanese Clans

îcåw¤Iv

æ7A2015N315ú

Waseda Daigaku kōtō kenkyūjo kiyō

[ Waseda Institute for Advanced Study Bulletin ]

Volume 7, 15 March 2015

Pages 17-27, pdf file

This article grew out of Suzuki's 2012 book, Nihon kodai ujizoku keifu no kiso-teki kenkyō (ú{Ãã°nÌîbI¤) <Basic Study on Genealogy of Ancient Japanese Clans>.

The abstract makes these observations (page 17).

The genealogies of ancient Japanese clans were created to declare their political positions and claim legitimacy for their service to the great kings in the Yamato sovereignty. Their genealogies, which include a great deal of semifictional content, and they are closely related to the "logic of rule". In other words, they are representations of the view of the world created by the ancient clans and used to support each other. By analyzing the genealogies, we can understand the actual situations of the ancient clans that we were not able to illuminate by using well-known historical materials. In addition, we can reveal the formation process of ancient Japan. However, these points are not well known to Japanese researchers, much less to foreign researchers. Furthermore, until now, the history of genealogical studies was compiled as necessary in case studies, or classified from a researcher's own particular viewpoint. Therefore, in this article, I have presented previous research in chronological order and by various categories, confirmed each category's respective significance, and advocated three methodologies for analyzing the genealogies. These will help us progress beyond previous studies

Suzuki makes this observation in the last part of the introduction (page 22).

3. Methodology for Analyzing Genealogy

In the discussion above, I presented the history of research on genealogy in modern times. I have categorized it into three stages. In the first stage, social interest in genealogy increased. In the second stage, the case studies of genealogy accumulated. In the third stage, studies on genealogy were systematized.

Particularly in the second stage, Saeki established the standard technique of the study. He tried to elucidate the actual situation of the ancient Japanese clans by closely examining the credibility of the genealogy. Then in the third stage, Mizoguchi pointed out the "multilayered structure," and Yoshie categorized genealogies into three types: "the genealogy of political positions," "the genealogy of marriages," and "the genealogy of the paternal line." From now on, based on these studies, we need to advance case study and synthetic study in parallel. . . .

Suzuki 2017a

éسM

ú{ÃãÌ°Æn`³

FgìO¶ÙA2017N

512y[W

Suzuki Masanobu

Nihon kodai no shizoku to keifu denshō

[Family clans and genealogy legends of Japan's early era]

Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kōbunkan, 2017

512 pages

Backcover blurb

The back cover promotes the book like this (my translation).

|

Ãã°Ìnâ`³ÍAPÈéÆnÌL^ÅÍÈ¢B»êÍÞçÌc檢ÂÌãAÇÌæ¤ÈE¶Å¤ Éòdµ½Ì©ð`¦½àÌÅA°Ì¡InÊ̳«ð壷é«íßÄ»ÀIÈððSÁÄ¢½Bw~¿©n}xâwCn}xÈÇ̪ÍðʵÄAnûxzEÕâJEOðÉôµ½Ãã°ÌÀÔÆðð¾·éÚÌêûB |

Genealogies and legends of early-era clans are not only records of family descent. Because they convey in what period, and in what sort of official capacity, their ancestors served the sovereign authority, they also assume the very realistic role of asserting the legitimacy of the clan's political position. A notable volume which, through analyzing Enchin zokushō keizu (~¿©n}) [Enchin's secular-surname descent-chart] [<The Lay Genealogy of Enchin>], Amabe-shi keizu (Cn}) [Amabe-family descent-chart (genealogy)], and other works, elucidates the actual conditions and various aspects of the early-era clans that were active in regional control (rule), rites, and diplomacy. |

Suzuki 2017b (2019)

The Japanese edition has been partly translated into English as follows.

Masanobu Suzuki

Clans and Genealogy in Ancient Japan

(Legends of Ancestor Worship)

[Routledge-WIAS Interdisciplinary Studies]

London and New York: Routledge (Taylor & Francis Group), 2017

First issued in paperback 2019

viii, 288 pages, paper cover

Routledge-WIAS Interdisciplinary Studies series books are edited by Hideaki Miyajima and Shinko Taniguchi, Waseda University, Japan.

Preface and acknowledgments

In the undated "Preface and acknowledgments", Suzuki gives special thanks to three professors he names at Waseda University, "for giving me the opportunity to publish research books in English" and signs the preface as follows (Suzuki 2017b 2019: viii).

Masanobu Suzuki

Senior Analyst for Textbooks

Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, Japan

Formerly Associate Professor at Waseda University

Ph.D. in Literature, Waseda University

Contents

- Analytical method for genealogy and legend

- Structure and source manuscripts of Enchin Keizu

- Consciousness of the bloodline of the Inagi-no-Obito Clan and Enchin

- Editing process and historical background of Amabe-uji Keizu

- Genealogical relationship of the Amane-no-Atai clan

- Legend of the Ōmiwa-no-Ason Clan and the eastern expedition

- Legend of the Ōmiwa-no-Ason clan and diplomacy View abstract

- Conclusions and future prospects

Publishers blurb

In recent years, there has been a noticeable and enthusiastic increase of interest in Buddhist temples and Shintō shrines in Japan. The legends of these temples and shrines are recorded in many historical manuscripts and these genealogies have such great significance that some of them have been registered as national treasures of Japan. They are indispensable to elucidate the history of these temples and shrines, in addition to the formation process of the ancient Japanese nation.

This book provides a comprehensive examination of the genealogies and legends of ancient Japanese clans. It advances the study of ancient Japanese history by utilizing new analytical perspective from not only the well-known historical manuscripts relied upon by previous researchers, but also valuable genealogies and legends that previous researchers largely neglected.

Comments

This book will be welcome by historians outside Japan, who are interested in clan genealogies in early Japan, and in the roles that genealogy played in the formation and maintenance of the political system that centered on the imperial family, which claimed descent from the Sun Goddess. It is not, however, without drawbacks for students of the political and social history of early Japan, who are unable to read Japanese sources.

Stages of genealogical studies

The book begins with an overview of the development of historical genealogy studies, which Suzuki divides into three periods (Suzuki 2017b, 2019: 1)

The first stage from the 1930s to the 1940s.

The second stage from the 1950s to the 1970s.

The third stage: after the 1980s.

Saeki Arikiyo, whose works I have introduced here, represents the second stage. The third stage is represented by scholars who divide themselves into "invariability" and "variability" schools -- referring the theories about whether, when, and how family clan genealogists change in terms of form and/or content. The "invariability" (fuhensei sÏ«) school holds that "genealogy began to be created in the fifth century, and the contents changed with the times, but its structure remained consistent until the ninth century." (Ibid. 12) In contrast, the "variability" (kahensei ÂÏ«) school emphasizes that "If the political position of a clan changes, the genealogy must also change. Otherwise, it would have no meaning" (Ibid. 11).

Suzuki states that "the relationship between the two characteristics ["invariability" and "variability"] is unclear." He feels that "[the two] characteristics are inseparable, and both are important essences of genealogy and legend." He calls the the presence of both characteristics a "multilayered structure", and he stresses the need to "re-examine the 'multilayered structure' of genealogy by analyzing the relationship between invariability and variability based on concrete examples in order to progress beyond the previous studies" -- and the standoff between the two schools. (Ibid. 12).

Concrete examples

Apart from the "theory" -- which will not interest many historians -- concrete examples of documented genealogies and related legends, from a variety of primary sources, are mostly what this book is about -- and why readers of English who are studying early Japan may find it worthwhile.

Students studying kanbun to gain access to historical texts will appreciate the fact that practically every page of Suzuki's book shows excerpts of kanbun texts which have been marked and otherwise punctuated for reading in Japanese -- followed by English summaries. The English summaries include some close paraphrasing, so readers sufficiently familiar with kanbun and English, if not also Japanese, can verify the quality of the English against the kanbun. It's not quite like having actual translations, but it's better than having only English.

While Suzuki captures the general purport of the cited genealogies, he sets the usual bad examples for usage of terms like "emigrate" and "immigrant". He is also inconsistent in his use of geopolitical terms -- showing the names of "Korean" entities in present-day ROK romanization in some cases, and Yamato in others -- seemingly uncertain of (or disinterested in) the vantage point from which the received chronologies were written, or how their authors or other contemporaries might have read them.

Example from Ryōno shūge

Each chapter has many "concrete examples", which Suzuki calls "articles". Suzuki numbers the examples Article 1, Article 2, et cetera, but rather than continue numbering from the previous chapter, he resets the number counter, so that the first example in every chapter is Article 1.

Suzuki presents the following "concrete example" from Ryō no shūge (ß`ð) (Article 4, page 204, and note 7, page 227).

SuzukiArticle 4 wßWðxðß15vO×ðøìTONiµêµj\êªú¾ (Ryō-no-Shūge, Botsurakugeban-Jō, Buyaku-Ryō 15, Daijōkanpu [Note 7] issued on November 8, the third year of Reiki [717]) O×ÆÛðBíESÏs»Añ±Igê AÛð俱ÆB Article 4 states that after Goguryeo and Baekje were ruined, people of these countries who emigrated to Japan, were exempted from a tax for the duration of their lives. There should have been people who were not recorded in the above mentioned historical materials. After Goguryeo was ruined, many people might have emigrated to Japan as they were forced to move. [Note 7] Daijōkanpu (¾¯) was an official document from Daijōkan (¾¯) to local governments. Daijōkan was a Grand Council of State. |

Comments

|

Example from Shinsen Shōjiroku

Shinsen Shōjiroku is only one of the many sources Suzuki cites, and he cites it rather sparsely. But SSSR students will want to check out the SSSR articles through the index.

Suzuki first substantial mention of SSSR comes in Chapter 3, "Consciousness of the bloodline of the Inagi-no-Obito Clan and Enchin". Suzuki's principle work has been on the so-called "Enchin Keizu" (~¿n}) -- which is supposed to be found in "Figure B" -- apparently an error for "Figure A" as there is no "Figure B" in the book. In any event, Suzuki mentions the Shinsen Shōjiroku in the course of describing a "movement to change the name of the Inagi-no-Obito clan" in Articles 17 and 18. He divides the movement into three periods, and describes the first like this (Suzuki 2017b 2019: page 52 and note 39, page 21, (parenthetic graphs) Suzuki's, [bracketed graphs] mine).

|

The first [period of the movement] is the era of Enryaku (782-806). In 799, the government issued Daijōkanpu to order clans to submit Honkeichō [{n ] in order to use the source manuscript for editing Shinsen Shōjiroku [Note 39] (Vï©^). In response to this order, the Inagi-no-Obito clan submitted their Honkeichō with the Iyo-no-Mimurawake-no-Kimi clan in 800. It is written that the Inagi-no-Obito clan and the Iyo-no-Mimurawake-no-Kimi clan built a Dōsō relationship [Note 40 (¯@) in the Honkeichō. [Note 39] Shinsenshōjiroku (Vï©^) was a newly compiled register of clan names and noble titles. It was edited in 815. [Note 40] Dōsō relationship (¯@) means that two clans shared a common ancestor. |

Shinsen Shōjiroku was not "edited in 815" but appears to have been formally released that year. It was presented to the emperor the year before, as completed, and so had to have been compiled before then. There is evidence that some elements of the record changed before its formal release, but that is not what Suzuki says.

The description of SSSR is immediately followed by "Article 19", which consists of a citation from Nihon kōki (ú{ãI), of an entry Suzuki calls "Article 19" and presents in Japanese and English like this (Ibid. 52, (parenthetic graphs) Suzuki's, [bracketed graphs] mine).

|

(Bojutsu, December of the eighteenth year of Enryaku [799], Nihonkōki [Note 41]) [Note 41] Nihonkōki (ú{ãI) is the history book that recorded the period after Shokunihongi [±ú{I]. It was edited in 840. |

This should read be translated as follows.

Nihonkōki, article (item) [of, dated] 6th day of 12th month of 18th year of Enryaku [Enryaku 18-12-6 = Gregorian 800-1-9 = 9 January 800]

"Amabe" and "Amane"

Suzuki makes most use of Shinsen Shōjiroku genealogies in Chapter 5, "Genealogical relationship of the Amane-no-Atai clan". The chapter explores reports in historical sources that illuminate the "Amabe family genealogy" (Amabe-shi keizu Cn}), an Important Cultural Property since 1976.

This, the longest chapter in the book, weighs 86 articles, some a page or more long, 94 end notes, and a 4-plus-page bibliography.

Coming on the heels of Chapter 4, "Editing process and historical background of Amabe-uji Keizu", the "Amane" in the title of Chapter 5 is puzzling -- especially since the chapter continues to explore the significance of "Amabe" family genealogy. One expects a plot twist that reveals "Amane" to be the truer name -- but that never happens. At the end of the day, one is left to image a typist hitting "n" instead of "b" in the title, and the error going unnoticed by serial proofreaders paid by the word. Alas, only "Amabe" is in the comprehensive index.

English editing

A book published by Routledge, through an arrangement with Waseda University, raises the question of whether the book originated in English or was translated from Japanese. Given the fact that Suzuki published his much longer study in Japanese first, one might think that the similarly titled but shorter English book is a partial translation or adaptation.. But there are no translation credits in the Routledge book. Two of the three Waseda University professors Suzuki thanks for giving him the opportunity to publish in English, however, are Hideaki Miyajima and Shinko Taniguchi, the editors of the Routledge-WAIS Interdisciplinary Series.