| Bibliographies and reviews | |||||

| Grading | Nationality | Population registers | Race | Minorities | Suicide |

Chosenseki in law and imagination

Reviews of "Chōsenseki" publications

First posted 15 November 2023

Last updated 23 November 2023

Chōsen statuses as facts

Before 1897

•

1897-1910

•

1910

•

1945-1952

•

1952-1966

•

1991

•

2012

Chōsenseki publications

Chong Young-hwan 2022

•

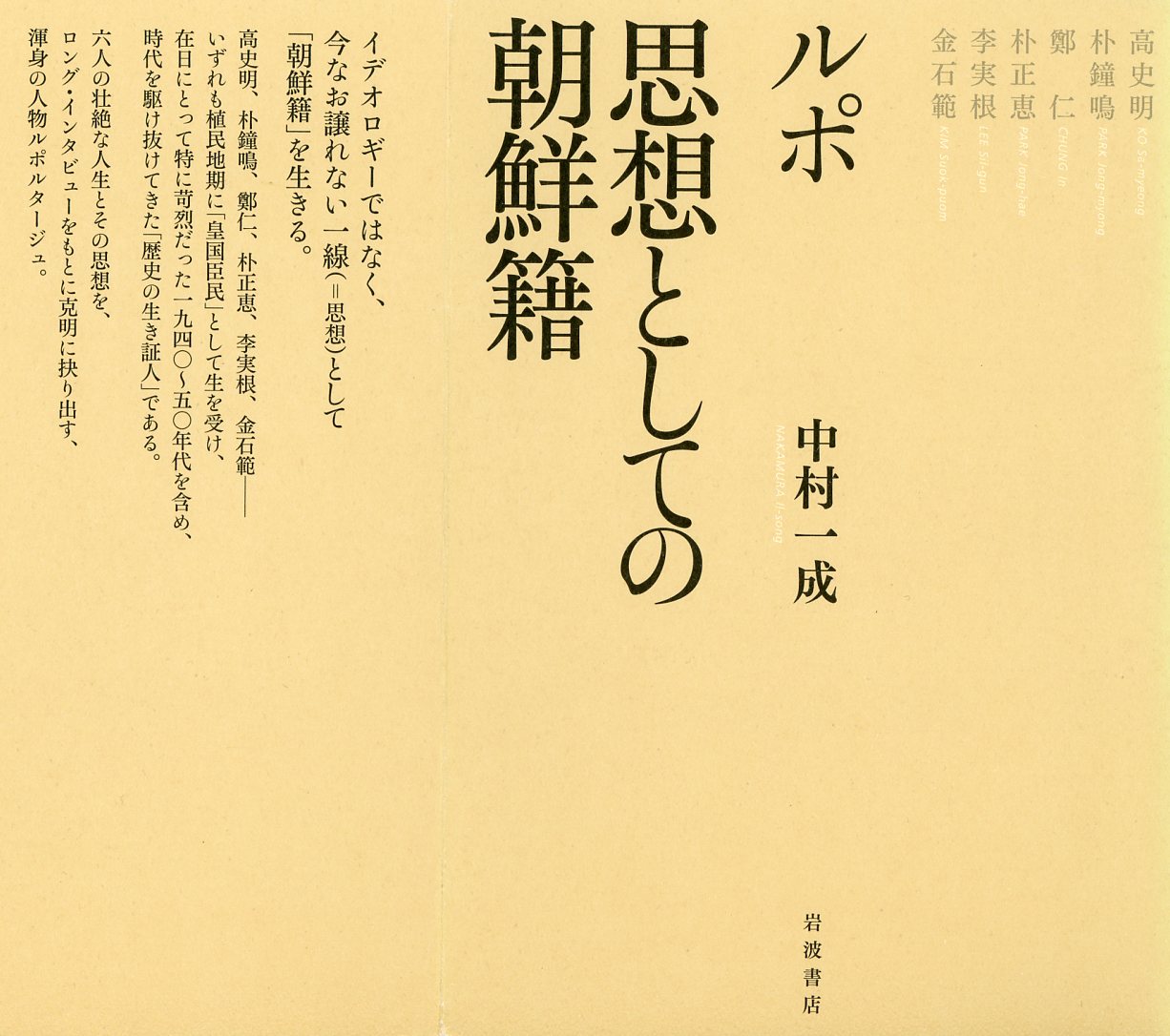

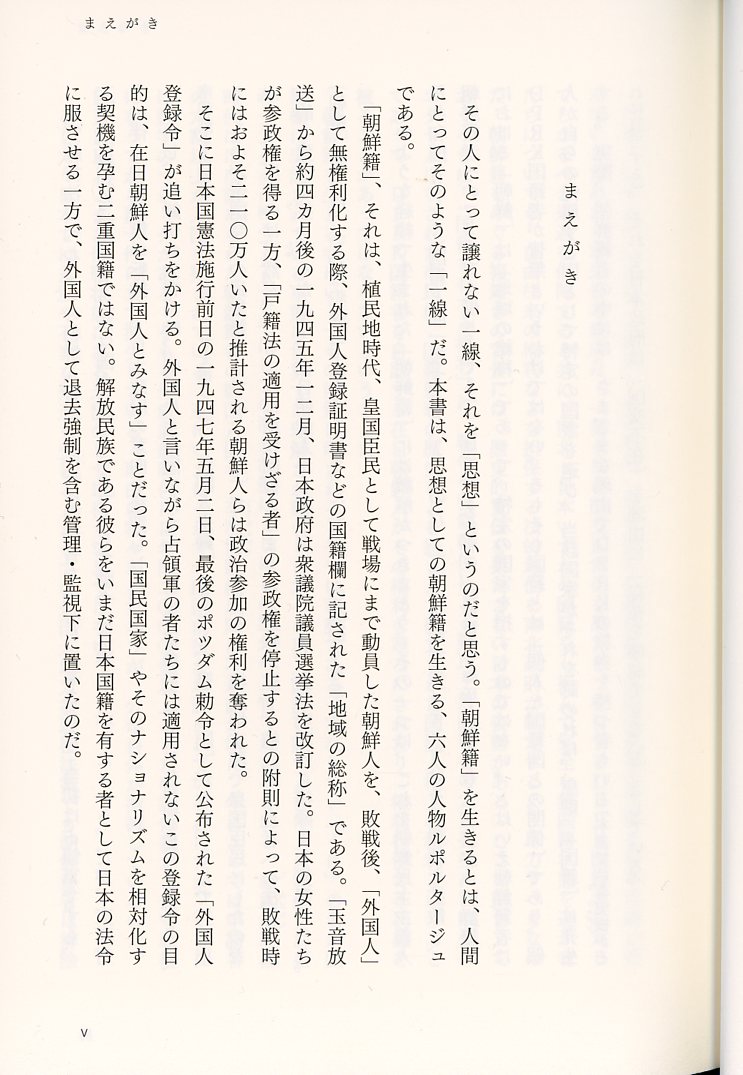

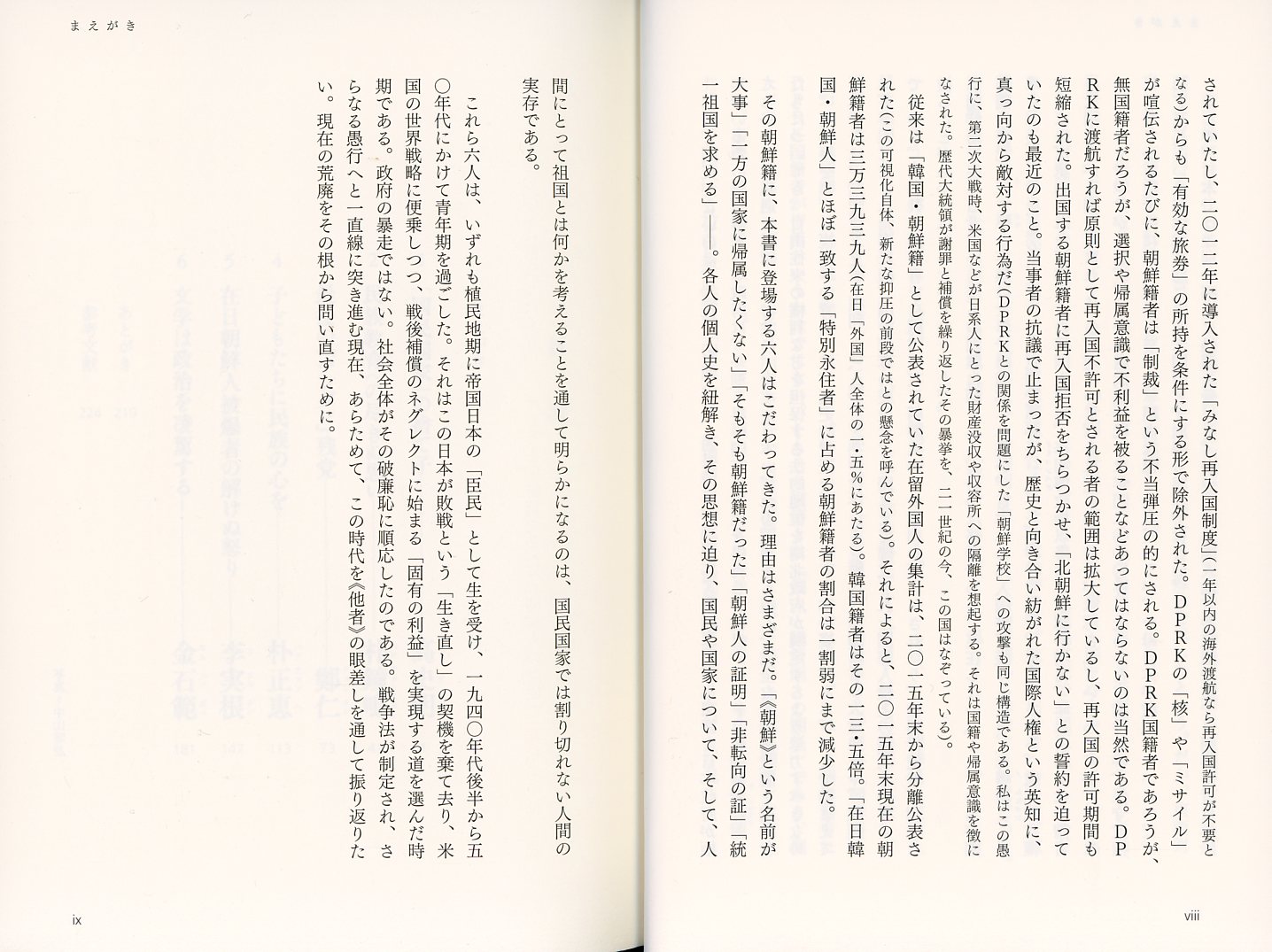

Nakamura Iruson (Ilsong) 2017

•

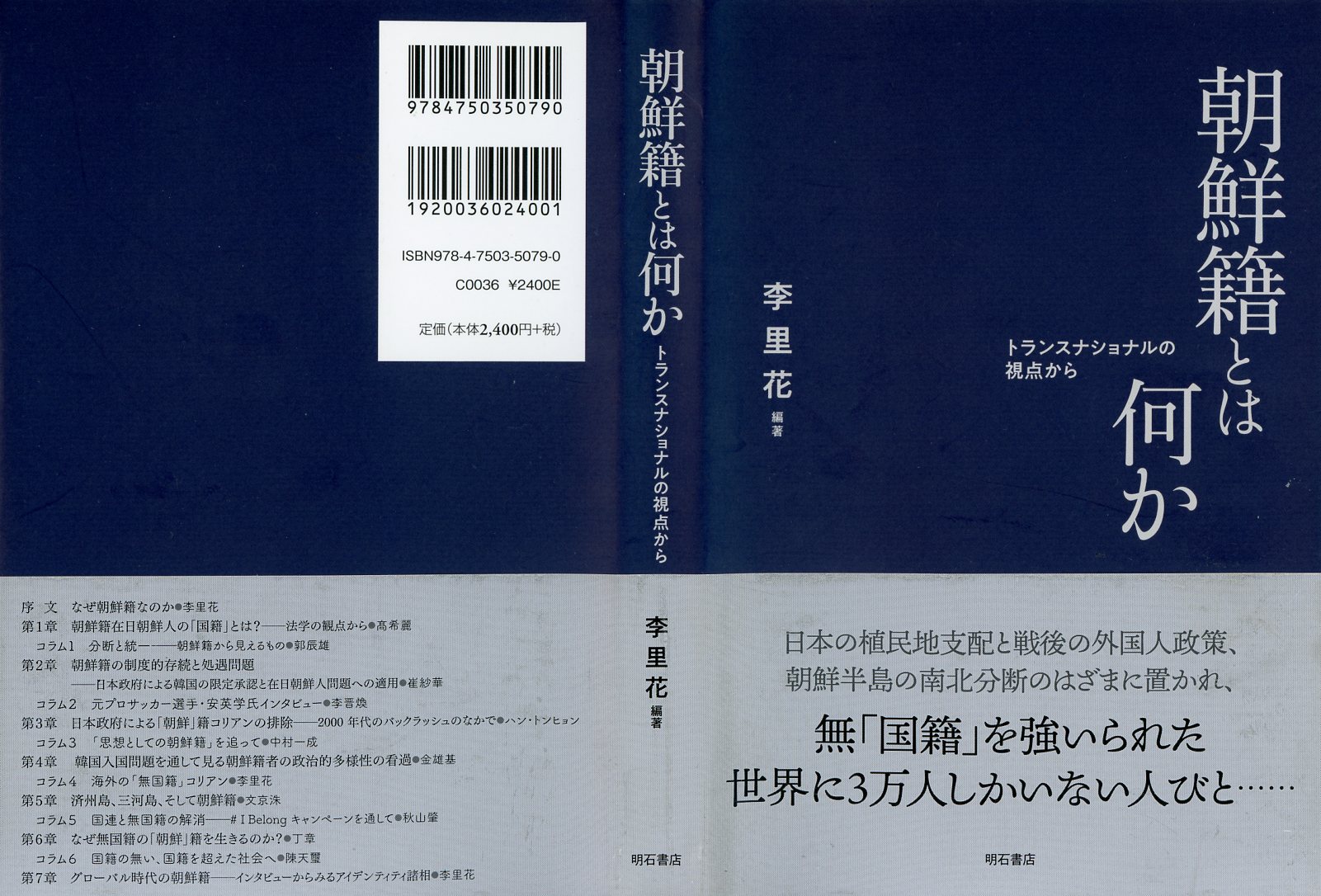

Rika Lee (Ri) 2020

•

Ri Rika 2021

•

Chatani Sayaka 2021

Chōsen statuses as facts

"Chosenseki" as a status in Japanese law began in 1910 after the Empire of Japan annexed the Empire of Korea as the Japanese territory of Chōsen. Korea's household registers became Chōsen's household registers. As because they now belonged to Japan and not Korea (which no longer existed), members of the registers became subjects of the Emperor of Japan and nationals of the Empire of Japan. In otherwords, Koreans became Chosenese, and Chosenese were Japanese.

It's that simple. Some people at the time regarded the annexation as illegal, but the nations of the world accepted it as a fait acompli and recognized that Chōsen was part of Japan. Both governments on the peninsula, established in 1948, view the annexation as illegal, and all its legal effects as null and void from its start in 1910. And practically everyone who writes about Japan's imperial years today, writes most of its legal effects out of their versions of history -- apparently in the belief that political undoings of the annexation justify the cancellation of its legal effects -- never mind that "Chōsenseki" -- its most important legal effect -- continues today, and cannot be understood with acknowledging its legal factuality and the momentum of its actuality.

Japan's treatment of "Chōsenseki" between 1945 and 1952, after 1952, and since 1965, is consistent with its treatment of "Chōsenseki" between 1910 and 1945. Namely, Japan agreed when unconditionally surrending to the Allied Powers in 1945 -- and confirmed in a peace treaty signed with the Allied Powers in 1951, effective in 1952 -- that Chōsen was no longer part of Japan. The problem was that Chōsen didn't belong to any state -- but had been divided into two states, ROK and DPRK, neither of which had been formally designated as a successor to Chōsen, but each of which claimed to be the sole successor, and both of which continue today to covet control and jursidiction of the other. When the peace treaty came into effect, without the usual provisions for changes in territorial sovereignty and nationality, ROK and DPRK were at war, and Japan had not yet concluded recognition treaties with either state. Yet within Japan's postwar borders in 1952 -- sans Chōsen, Taiwan, Karafuto, Okinawa, and several islands and island groups affiliated with Hokkaidō, Tōkyō, and Kagoshima prefectures -- found itself the home of over 600,000 Chosenese who, as Japanese at the time Japan surrendered, remained in Occupied Japan -- as Japanese partly treated as aliens -- rather than be "repatriated" to the peninsula, where about one-third had never lived. Japan, having forfeited all rights over the nationality of people in Chōsen registers (Chōsenseki 朝鮮籍), had little choice but to regard the formal separation of Chōsen from Japan in 1952 as tantamount to a separation of Chosenese (Chōsenjin) -- i.e., people in Chōsenseki -- from its nationality.

Concomitant with separating Chosenese from Japanese nationality, Japan did two things that were actually very astute from a practical legal standpoint. First, Japan exempted practically all Chosenese in Japan from acquiring a status of residence -- as was required of other aliens (including a few Chosenese) -- but created a special status for them, a provisional status tantamount to permanent residence, pending the conclusion of status agreements with ROK and/or DPRK. And second, rather than treat Chosenese as stateless aliens, Japan classified them as Chosensenseki aliens, thus deeming Chosenseki the fictitious (deemed) nationality of Chōsen as a fictitious state. And Chōsen as a legal fiction -- or "legacy entity" as I call it -- continues to be the foundation for the legal status of Chōsenseki -- a fact no matter whether it has the blessings of post-colonialist professors who are bent on insisting that Chosenese were not really Japanese.

- In 1910, Japan annexed the Empire of Korea as Chosen.

- Imperial Korean nationality became Chosenese territoriality hence Japanese nationality.

- In 1945, when surrendering to the Allied Powers, Japan agreed that it would lose Chosen.

- Japan surrendered its control and jurisdiction over Chosen in 1945.

- Chosenese were deemed aliens for purposes of repatriation, border control, and registration.

- However, they remained Japanese until appropriate bilateral treaties established nationality choices.

- The San Francisco Peace Treaty finalized Japan's loss of Chosen as a territory.

- The treaty did not, however, make provisions for nationality choices.

- 1951-1952 Japan-ROK talks produced a ready to-sign-status agreement.

- The status agreement provided for permanent resident of qualified Chosenseki persons in Japan.

- However, it made no provisions for nationality choices (ROK did not recognize that Chosenseki persons were Japanese).

- The agreement could not be signed because the parties disagreed on other matters on the table.

- This meant Japan would lose Chosen without the usual nationality settlements that accompany territorial changes.

- Since nationality is linked with registers, separation of Chosen from Japan meant separation of Chosenseki from Japanese nationality.

- This would leave Chosenseki stateless.

- Japan, envisioning that the nationality issue would be resolved in future talks and agreements, treated Chosenseki as a virtual nationality.

- Chosenseki became a legal fiction, representing the peninsular nationality that would have restored had the peninsula become a state.

- In the meantime, Japan exempted Chosenseki from ordinary alien status of residence requirements.

- Qualified Chosenseki aliens were provisionally accorded treatment as permanent residents pending status agreements with ROK and/or DPRK.

- The 1965 Japan-ROK status agreement confirmed that Chosenseki aliens who migrated to ROK nationality would have permanent residence.

- People who remained Chosenseki continued to be treated as provisional permanent residents.

- In 1991, all special statuses accorded people who had lost Japan's nationality, as an artifact of the territorial separations occasioned by the San Francisco Peace Treaty, were consolidated into the Special Permanent Resident (SPR) status -- regardless of their present alien nationality, if they had been in Japan when Japan surrendered, and continued to reside in Japan, including Chosenseki, and former Chosenseki who had migrated to ROK or another nationality.

- The unsigned 1951-1952 status agreement, and the 1965 status agreement, did in fact give Chosenseki nationality choices, and the few thousand Chosenseki aliens in Japan today continue to have these choices -- (1) remain Chosenseki as a deemed nationality (legal fiction representing a legacy status), or (2) migrate to a non-fictional nationality, recognized by Japan, including Japanese should they wish to naturalize.

- In other words, Chosenseki has always been -- and continues to be -- a legal fact -- whether or not "Chosen" was ever legal, and whether or not Japan's critics don't understand the meaning of "Chosen" as a legacy entity with a legally fictitious (deemed) nationality called "Chosenseki".

- Japan has never treated "Chosenseki" as stateless.

- The status of "Chosenseki" as a fictitious nationality is in fact a rather practical solution to status problems that continue because postwar nationality issues remain unsettled.

- What choices would a status agreement between Japan and DPRK provide?

- Would Chosenseki become DPRK nationals by decree, or would they have a choice of Japanese nationality, or perhaps to remain "Chosenseki" as a fictitious legacy nationality?

Chosen before 1897

Forthcoming.

Kankoku 1897-1910

Forthcoming.

Chosen 1910

Forthcoming.

Chosen 1945-1952

Forthcoming.

Chosen 1966

Forthcoming.

Chosen 1991

Forthcoming.

Chosen 2012

Forthcoming.

Chosenseki publications

| Chong Young-hwan 鄭栄桓 | ||

| 2018 |

Chong 2022鄭栄桓 Chong Young-hwan | |

Chong Young-hwan国籍か、それとも出身地かーー。 1947年5月2日、日本の外国人法制に登場し、今日に至るまで存続している「朝鮮籍」。植民地支配からの解放後も日本で暮らし続けた朝鮮人たちに与えられたこの奇妙な「国籍」の歴史を、日韓の外交文書、法務省や地方自治体の行政文書、裁判記録、そして政党・民族団体の残した文書などの一次史料を精緻に読み解くことで明らかにする。 目次 序 章 朝鮮籍をめぐる問い 第一章 朝鮮籍の誕生ーー「地域籍」から「出身地」へ 第二章 南北分断の傷痕ーー韓国籍の登場 第三章 戦時下の「国籍選択の自由」ーー朝鮮戦争と国籍問題 第四章 国籍に刻まれた戦争ーーいかにして朝鮮籍は継続したか 第五章 同床異夢の「朝鮮国籍」ーー停戦から帰国事業へ 第六章 日韓条約体制と朝鮮国籍書換運動 補 章 再入国許可制度と在日朝鮮人 終 章 朝鮮籍という錨 あとがき 著者について 鄭 栄桓(チョン ヨンファン) 明治学院大学教養教育センター教授(歴史学)。1980年、千葉県に生まれる。明治学院大学法学部卒、一橋大学大学院社会学研究科博士課程修了(社会学博士)。立命館大学コリア研究センター専任研究員、明治学院大学教養教育センター専任講師、准教授を経て現職。専門は朝鮮近現代史・在日朝鮮人史。著書に『朝鮮独立への隘路 在日朝鮮人の解放五年史』(法政大学出版局、2013年、第13回林鍾國賞受賞〔朝鮮語版〕)、『忘却のための「和解」 『帝国の慰安婦』と日本の責任』(世織書房、2016年)、訳書に権赫泰『平和なき「平和主義」 戦後日本の思想と運動』(法政大学出版局、2016年)等がある。 |

||

| Rika Lee | ||

| 2020-02-06 |

Ri Rika 2021-02-06Rika Lee | |

Rika LeeRi_Rika_2020_02-06_Stateless_chosenseki_yabyomiuricojp.jpg

|

||

| Ri Rika (Rika Lee) 李里花 | ||||||||||||||

| 2021 |

Ri Rika 2021李里花 (編著) Ri Rika (compiler, author) This book is a collection of 7 chapters, including the final chapater by compiler cum author Ri Rika. Each colum except Ri's is followed a "column" consisting of commentary on the chapter, 4 by other contributors, but 2 by Ri -- for a total of 11 contributors including Ri. Ri also contributes a 9-page preface titled "Why Chōsenseki?" (Naze Chōsenseki na no ka なぜ朝鮮籍なのか), in which she virtually answers the "What is Chōsenseki?" question raised by the title. She also wrote the 6-page afterword, which she dated 15 August 2020 -- the 75th anniversary of the day most Japanese of Chōsen registration, as subjects and nationals of Imperial Japan celebrated as the day they were "liberated" from Japan's colonial rule of the Chōsen peninsula. 15 August 1945, the day Emperor Hirohito ordered his field commanders to cease fire, and otherwise end hostilities in the Greater East Asia and Pacific War, is also celebrated as "liberation day" in both the Republic of Korea (ROK) and the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), both of which were founded in 1948, on respectively the southern and northern half halves of the peninsular, which the Instrument of Surrender signed between Japan and the Allied Powers on 2 September 1945 agreed to divide at the 38th parallel. The Soviet Union invaded and occupied the northern occupation zone on. The Commanding General of the United States Army Forces in Korea accepted Japan's surrender in the southern occupation zone on 9 September 1945. | |||||||||||||

Ri RikaRi Rika was born in the United States to a RESUME Ri Rika writes were name in graphs (李里花) she reads in kana as "Ri Rika" (リ・リカ) but romanizes "Rika Lee". When speaking Japanese, she pronounces her name "Ri Rika" -- a Sino-Japanese reading of the graphs. If read in Sino-Korean/Chosenese, her name would be probably be hangulized as 이이화 (I I-hwa) or 리리화 (Ri Ri-hwa), in which "I" is more common in the south and "Ri" is more likely in the north, as dialect variations of the Korean/Chosenese language. At the time Ri Rika's book was published, she was an associate professor in the Faculty of Policy Studies (Sōgō seisaku gakubu 総合政策学部 "General policy department") at Chuo University (Chūō Daigaku) in Tokyo, where she specialized in historical sociology, migrant (immigration) studies, and Pacific Rim studies. "I myself am not Chōsenseki, but was raised while moving back and forth between Japan and America, [having been born] between a Zainichi Korian mother and a Korian-Amerikan father. 私自身は朝鮮籍ではなく、在日コリアンの母とコリアン・アメリカンの父の間で日米を往来しながら育ちました。本書の「あとがき」にも書いたように、大学を卒業してから「世の中の仕組みがわからないと先に進むことができない」という漠然とした不安感から大学院に進学しました。 そしてそこでアメリカや東アジアの人種エスニシティ研究やナショナリズム研究を学んでいく中で、誰にとっても自由で平等な社会を目指していきたいと思うようになりました。 これまで日本とアメリカ、ハワイで調査を実施し、移民やマイノリティのアイデンティティやナショナリズム、トランスナショナリズムについて研究してきました。最近はマイノリティ文化の表象をめぐる問題や「自国民/外国人」の枠組みを超える研究等に取り組んでいます。 朝鮮籍とは、植民地期朝鮮から日本に「移住した」朝鮮人とその子孫を分類するために、戦後の日本で創り出されたカテゴリーである。本書は、朝鮮籍をめぐる歴史的変遷をたどりながら、朝鮮籍の人が直面したリアリティにも焦点を当てることで、その実像に迫ろうとするものである。 ○目次 序文 なぜ朝鮮籍なのか (李里花) 第1章 朝鮮籍在日朝鮮人の「国籍」とは――?法学の観点から (髙希麗) 1 はじめに 2 日本における外国人としての在日朝鮮人――朝鮮籍のはじまり 3 朝鮮半島における在外(海外)同胞としての在日朝鮮人――国民の範囲 4 国籍未確認としての朝鮮籍者――国民国家の狭間で 5 おわりに――こぼれ落ちる存在への並走 コラム1 分断と統一――朝鮮籍から見えるもの (郭辰雄) 第2章 朝鮮籍の制度的存続と処遇問題――日本政府による韓国の限定承認と在日朝鮮人問題への適用 (崔紗華) 1 はじめに 2 前史――朝鮮籍の誕生と日本国籍の喪失 3 日本政府の限定承認論と朝鮮籍の制度的存続 4 日本政府の限定承認論と在日朝鮮人の処遇問題 6 おわりに コラム2 元プロサッカー選手・安英学氏インタビュー (李晋煥) 第3章日本政府による「朝鮮」籍コリアンの排除――2000 年代のバックラッシュのなかで (ハン・トンヒョン) 1 はじめに 2 在留外国人統計における「朝鮮・韓国」の分離 3 海外渡航に際して「誓約書」を強要 4 韓国渡航をめぐる「みなし再入国」運用の混乱 5 分離集計のその先と朝鮮学校の処遇 6 おわりに コラム3 「思想としての朝鮮籍」を追って (中村一成) 第4章 韓国入国問題を通して見る朝鮮籍者の政治的多様性の看過 (金雄基) 1 はじめに 2 日本における朝鮮籍者をめぐる処遇の歴史的変遷 3 南北朝鮮との関係性によって明らかになる朝鮮籍者の政治的多様性 4 韓国は朝鮮籍者をどのように処遇してきたのか 5 「非北」朝鮮籍者による韓国社会に対する政治的主張 6 結論 コラム4 海外の「無国籍」コリアン (李里花) 第5章 済州島、三河島、そして朝鮮籍 (文京洙) 1 一世と二世 2 三河島の済州人――泉靖一の調査から 3 「朝鮮籍」を生きて 4 「韓国籍」へ コラム5 国連と無国籍の解消――# I Belong キャンペーンを通して (秋山肇) 第6章 なぜ無国籍の「朝鮮」籍を生きるのか? (丁章) コラム6 国籍の無い、国籍を超えた社会へ (陳天璽) 第7章 グローバル時代の朝鮮籍――インタビューからみるアイデンティティ諸相 (李里花) 1 はじめに 2 グローバル化、ヘイト、そして韓流 3 インタビューからみる朝鮮籍のアイデンティティ諸相 4 おわりに あとがき (李里花) 著者について ○編著者紹介 李里花(リ・リカ) 中央大学准教授。社会学博士。専門は、歴史社会学、移民研究、環太平洋地域研究。東京都立国際高等学校、中央大学総合政策学部卒業後、一橋大学大学院社会学研究科修士課程・博士課程修了。博士課程在学中に、ハワイ大学大学院に留学し、その後ハワイ大学コリアン研究センター客員研究員、韓国高麗大学アジア問題研究所コリアンディアスポラセンター客員研究員を歴任。現在日本移民学会理事・事務局長。主な研究に、『〈国がない〉ディアスポラの歴史:戦前のハワイにおけるコリア系移民のナショナリズムとアイデンティティ1903-1945』(かんよう出版、2015 年)、「?????????? ???? ?????? ???????? ????(ハワイにおけるコリア系移民女性の近代化と文化)」(?????? ??)?????? ?? ????『???? ???? ?????? ???? ???? ???? ?? ????』韓国学中央研究院出版部(韓国)2019 年(119-146)、「Stateless Identityof Korean Diaspora: The Second Generations in prewar Hawai'i and postwarJapan」『Japanese Journal of Policy and Culture』(28) 2020 年(55-69)、「今なぜ〈トランスナショナル〉なのか――日本における移民研究を考える」『移民研究年報』(26), 2020 年(3-8) 等がある。自身は朝鮮籍ではなく、在日コリアンの母とコリアン・アメリカンの父の間で日米を往来しながら育った。最近は「自国民/外国人」の枠組みを超える研究や活動に取り 組んでいる。詳しくはhttps://yab.yomiuri.co.jp/adv/chuo/research/20200123.php。 ○執筆者紹介 髙希麗(コウ・ヒリョ) 公益財団法人後藤・安田記念東京都市研究所研究員。専門は憲法であり、国籍や国民概念について日本、韓国、ドイツ(EU)などを対象に研究している。 崔紗華(チェ・サファ) 同志社大学社会学部教育文化学科助教。専門は国際関係史、人の移動。 ハン・トンヒョン(韓東賢) 日本映画大学准教授。専攻は社会学、専門はナショナリズムとエスニシティ、マイノリティ・マジョリティの関係やアイデンティティ、差別の問題など。 金雄基(キム・ウンギ) 韓国翰林大学校日本学研究所 HK 教授。専門は東アジア政治史、近年の研究テーマは韓国の在外同胞としての在日コリアン。 文京洙(ムン・ギョンス) 立命館大学名誉教授。現在、「済州島四・三事件を考える会」会員、在日総合誌『抗路』編集委員、『済州日報』論説委員。 丁章(チョン・ヂャン) 在日サラム(コリアン)三世。無国籍(朝鮮籍)。詩人。在日総合誌『抗路』編集委員(1 号~ 6 号)。無国籍ネットワーク運営委員。 郭辰雄(カク・チヌン) 特定非営利活動法人コリアNGOセンター代表理事。 李晋煥(リ・ジナン) 株式会社明石書店に勤務。 中村一成(なかむら・いるそん) ジャーナリスト。主なテーマは在日朝鮮人や移住労働者など、非・国民を取り巻く人権問題や死刑など。2000 年代以降は中東に赴き、パレスチナ難民との出会いも重ねてきた。映画評も執筆する。 秋山肇(あきやま・はじめ) 筑波大学人文社会系助教。専門は、憲法、国際法、国際政治、国際機構論、平和研究。国籍・無国籍の研究を通して、国家と人間の関係性について分析している。 陳天璽(チェン・ティェンシ/ちん・てんじ ) 早稲田大学国際学術院教授、無国籍ネットワーク代表理事。移民、無国籍者に注目した研究に従事。 |

||||||||||||||

| Chatani Sayaka 茶谷さやか | ||

| 2021 |

Chatani Sayaka 2021 | |

Chatani Sayaka |

||