| Bibliographies and reviews | |||||

| Grading | Nationality | Population registers | Race | Minorities | Suicide |

Tei Taikin on nationalism and Koreans in Japan

The wrongs of "Zainichi" victimhood and the rights of naturalization

First posted 15 February 2006

Last updated 31 July 2024

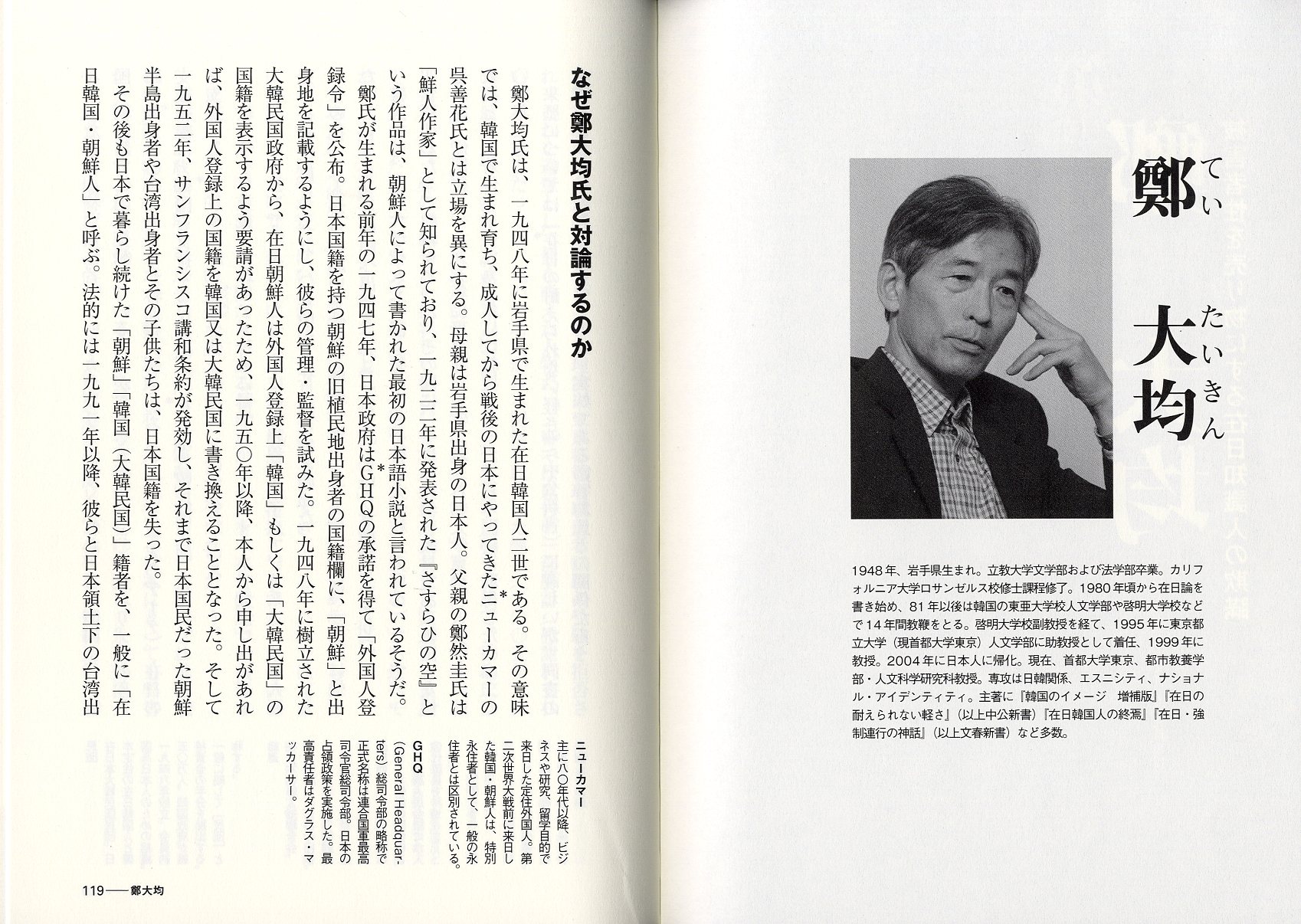

Tei Taikin A voice for Korean and Chosenese belonging in Japan

Tei Taikin, born in 1948 in Occupied Japan, into Japanese nationality and Chosenese subnationality, is today the most cogent advocate of naturalization as an alternative to Zainichiism. He is also an anthologist of writings by Chosenese and Interiorites portraying Chōsen during the Japan-Korea annexation period.

Tei Taikin has been a friend for half a century, and I count myself as one of his critical fans. This introduction to Tei's books and selected articles begins with a general sketch of his family history. I have not rated his writings according to the color scheme I developed for the Bibliographies section of this website. Most would be "A" (green) -- "An excellent source with few serious problems." A few would be "B" (blue) -- "A good source with some serious problems".

Because Tei's earliest books were examinations of nationalism in Korea and Japan, I first introduced his writings with kindred works by others on the Korean issues in Japan page under "Viva nationalism" in the "History" section of this website. And I reviewed his books on Zainichi issue on the "Minorities" page in the "Bibliography" section. I then decided to dedicate the "Korean issues in Japan" page to Ken Kanryō comics and related books. At which point I created this page as a place to bring together all of my reviews of Tei's writings.

Tei Taikin

Tei Taikin is the strongest proponent in Japan of naturalization as the only logical way for Koreans and Chosenese in Japan to secure political rights to fully participate in Japanese society -- as Japanese. He is also a prolific critic of ethnonationalism in both Korea and Japan, and of "Zainichi" victimhood advocacy, which I call "Zainichiism".

No other writer in Japan today has contributed more to the forging of an objective (as opposed to ideological) understanding of Korean and Japanese nationalism and their continuing consequences for, and effects on, Koreans in Japan than Tei Taikin, who used to also write as Chung Daekyun. Several of Tei's most important titles have been brought out in the paperback series of two major publishing houses.

Tei has also contributed numerous articles to newspapers, magazines, and other books. Some of his own books are compilations of articles published in periodicals, while others were originally written as books.

Tei's books -- unlike those of Kang Sang-jung, which have helped popularize the Zainichi victimhood that Tei opposes -- have not been the kind that TV talk shows like to hype into bestsellers. His views, however, are slowly but surely affecting public understanding what he calls the "Japan-Korea Union period" (Nik-Kan heigō-ki 日韓併合期) -- the period when Korea was annexed to Japan as Chōsen, Chosenese were Japanese, and numerous Chosenese migrated to the prefectural Interior (Naichi 内地), most voluntary -- including Tei's father, a novelist, poet, and magazine editor who supported Japan's Pan-Asian ambitions.

Tei has also been the leading proponent of naturalization. Defining "Zainichi" as Korean aliens who are recognized as Special Permanent Residents, he argues -- correctly, I believe -- that remaining Zainichi is to maintain a legal status tied to the past, rather than a status tied to the present and the future. Remaining Zainichi is to be a national of a real foreign country (most likely the Republic of Korea but possible one of about 50 other countries) or a fictitious country (Chōsen) -- while legally domiciled in Japan. Practically all Zainichi have been born and raised in Japan, are are linguistically, culturally, and socially most familiar with Japan, but remain politically, and are most likely politically and otherwise estranged from their countries of nationality. Naturalizing means becoming a full member of the country in which one was probably born and raised and knows as a native, where one is most comfortable and prefers to live.

Tei received a BA from St. Paul's University in Tokyo and an MA from the University of California at Los Angeles. He taught Japanese at universities in Korea from 1981-1995 while continuing his research and writing on Korea-Japan relations and ethnicity, and became a professor at Tokyo Metropolitan University in 1995.

I first met Tei in 1975, when he called himself Chung and also Saitō -- his mother's original family name. We have kept in touch over the years and he, more than anyone, has inspired my current views of ethnicity, nationalism, and the importance of Japanese nationality as a mark of membership in Japan's sovereign, democratic, civil, raceless nation.

Tei's family background

Forthcoming

Tei's struggle with naturalization

To naturalize in Japan, or not, is a question every alien in Japan is in a position to ask after residing in Japan long enough to feel that Japan is where one belongs. Practically all aliens who have lived in Japan for several years, and have established their lives in Japan, are legally qualified to apply for permission to naturalize. And practically all aliens determined to naturalize, if willing to submit to the not especially difficult naturalization procededures, will be be approved for naturalization and become Japanese.

Procedures are generally easier for foreigners born in Japan and for foreigners with a Japanese parent. But they are typically easiest for foreigners who reside in Japan as Special Permanent Residents, referring to a legacy population of prefecturally domiciled Taiwanese and Chosenese who lost Japan's nationality on 28 April 1952 when Japan formally lost Taiwan and Chōsen, and their descendants if born, raised, and domiciled in Japanpopulation former Japanese nationals of aliens who either a population of that originated on of Japan, meaning people who were residing in the prefectural Interior of the Empire of Japan and enrolled in a Taiwan or Chōsen household register, or (2) a descendant of such a person who was born and raised in Occupied Japan to a on or after 3 September 1952 and before 27 April 1952, and (3) lost Japan's nationality on or before 2 September 1945, remained in Japan, and lost Japan's nationality on 28 April 1952 when Japan lost Taiwan and Chōsen and raised in prefectural Japan, continually domiciled in Japan' prefectures, and who (1) were born Japanese but lost Japan's nationality in 1952 when Japan lost Taiwan and Chōsen, or (2) were born aliens to daliensborn and raised in Japan to parents or who lost Japan's nationality in 1952 were descendants of such former Japanese.

Tei Taikin qualified as

approvpractically all will , is a choice every alien who has resided in Japan for several years andTei's bout with naturazlForthcoming.

Tei's mother, Saitō Ai (斎藤アイ 1909-2003), was born in Iwate prefecture, in the Naichi (Interior) jurisdiction of the Empire of Japan. When his parents married in the 1940s, she entered his father's Chōsen register, and as an effect of this status migration from a Naichi to a Chōsen register became Chosenese, as did their three children under the family lineage rules that applied to territorial registers.

The entire family, including Tei's older brother (1944-2000) and younger sister (b1950), lost their Japanese nationality the day the San Francisco Peace Treaty came into effect in 1952. When Tei's mother naturalized in 1985, she wrote in a letter to him -- "Yesterday I returned my Gaitō (Alien Registration Certificate), and was liberated" (Tei 2006, page 63).

In 1960, Tei's mother and her children had to go to the Sendai Family Court to confirm whether they wished to remain in Japan or go to ROK with Tei's father. The day they appeared for the hearing, Tei recalls, they encountered a skirmish between police and demonstrators protesting the talks then resuming between ROK and Japan. His father, he believes, was also in Sendai at the time, but he did not see him. The last time he saw his father in Japan was a few months earlier, when his father, having decided to return to Korea, called a taxi, something unheard of in their family, which he had never done, and he pressured the children to go with him. They resisted, and Tei thinks someone might have reported the commotion, because the police came to intervene in the domestic feud as the neighbors looked on from a distance. Looking back on what he counts among the more nightmarish experiences of his youth, Tei now thinks that the situation was probably the most painful for his father. But at the time, he took a little joy in seeing his father in such misery. (Tei 2006, pages 56-57)

The artifacts of legal status

Writing with the emotional detachment of a good novelist dramatizing his own life, Tei does not wax sentimental or mince his words. His descriptions of his parents and siblings, and of his relations with them and ultimately with himself, are passionately honest.

Tei's family story is very personal and unique, as all such stories are for those who experienced them. Some elements of his family story are atypical of families generally, while others are common to families in similar circumstances. One of the commonalities in his family story is the manner in which the laws of the times affected the legal status of his parents and then their children.

Tei's father, the novelist and critic Chŏng Yŏn'gyu or Tei Zenkei (鄭然圭 1899-1979 정연규), was born two years after Chosŏn became the Empire of Korea, and eleven years before the Empire of Korea joined the Empire of Japan as Chōsen. As an effect of the annexation, Tei, like other Koreans, became Chosenese subjects of Japan and as such also Japanese.

Tei's father, born in the Empire of Korea, to a family that was considered Korean because they had a household register affiliated with a local polity within the country. Laws and regulations concerning household registration were strenghened As a child of parents in a household register affiliated with Chōsen, as Korea had been renamed when annexed by Japan in 1910, Tei was also a Chōsenjin (Chonesese, Korean) under Japanese law, hence a Japanese national. At the same time, under the status rules established by Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers in Occupied Japan, and under Japanese laws and ordinances affected by SCAP directives, he was "non-Japanese" of Japanese nationality for certain legal purposes until the nationality of Chosenese (Koreans) and Taiwanese (Formosans) could be determined by treaties between Japan and concerned states.

In 1952, when Chōsen and Taiwan were formally separated from Japan's sovereign territory as a result of the effects of the San Francisco Peace Treaty, Chosenese and Taiwanese lost their Japanese nationality. Hence Tei and his family -- his father (born in Korea in 1899), his mother (born in Iwate in 1909), his older brother (born in Tokyo in 1944), and his younger sister (born in Iwate in 1950) -- became aliens of Chōsen nationality. This was a virtual rather than actual nationality, since the territorial "nation" of Chōsen had no state. Or, more precisely, the former Japanese territory of Chōsen had two states, ROK and DPRK, both of which claimed to be the sole legitimate government of "liberated Korea". In 1950, however, DPRK had invaded ROK, and in 1952 the two states were still at war. Talks between ROK and Japan in late 1951 and early 1952, to establish normal relations and resolve issues related to the status of Koreans in Japan, stalled, and though they resumed several times, the two countries did not sign a normalization treaty and status agreement until 1965. While Japan at this point recognized ROK as the sole legal government of Chōsen (in the Japanese version of the normalization treaty), the treaty did not resolve issues between Japan and DPRK, and the status agreement covered only Koreans in Japan who sought and confirmed their possession of ROK nationality.

Tei -- having lost his Japanese nationality in 1952 -- became an alien in Japan with the nationality of "Chōsen" -- referring to Japan's former peninsular territory, now a stateless entity. In 1948, the Republic of Korea (ROK) was established in the south, and the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK) was established in the north, and in 1952 the two new states were at war. Japan and ROK finally normalized their relationship in 1965, when they signed a basic treaty, as well as status agreement that governed the treatment of ROK nationals in Japan. The status agreement, effective from 1966, allowed Chosenese to obtain Korean nationality through the ROK government. Tei's father did so and returned to the peninsula, where he lived until his death. Tei, his mother, and siblings remained in Japan, but soon also became Koreans. Tei's mother later naturalized in Japan, and in 2004, Tei also became Japanese.

Chung and Wetherall 1979-1980Chung Daekyun and Uezarooru Uiriamu KawasakiIt is of some interest to note that Chong Hyanggyun, like her brother Tei Taikin (then Chung Daekyun), had lived for a while in Kawasaki, where there is a substantial Korean neighborhood (Chōsen buraku). When I first met Tei in the late 1970s, he was working part-time in the Kawasaki public library while also participating in Korean community activities in the city. He guided me around the Korean neighborhood -- or neighborhoods, as the distribution of obviously and less obviously Korean shops and homes was complex. For reasons owing mainly to his generosity rather than to any significant contribution from me, Tei listed me as the junior author of a two-part series of articles he (rather than we) wrote and published in 1979 and 1980 on foreign residents in Japan, especially Koreans, and especially Koreans in Kawasaki 鄭大均、ウェザロール・ウィリアム Chung Daekyun and Wetherall William Sato KatsumiAlso of some interest is the fact that this journal, published by the Nihon Chōsen Kenkyūjo (Japan Chōsen Research Institute) [Japan Chōsen Research Institute], was edited by Satō Katsumi. Satō was instrumental in the support of Pak Chong Sok from the start of Pak v Hitachi in 1970, and is the first listed of the two representative editor of the book published by Pak's principal support group in 1974 shortly after Pak won the case (see below). Satō Katsumi, born in 1929, participated in the movement, led mainly by communist Koreans in Japan, for Koreans to "return" to the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK). He himself twice accompanied groups of returnees to DRPK, in 1962 and 1964, and received awards from the DPRK Red Cross. A dedicated member at the of the Japan Communist Party since the late 1940s, Satō participated in all manner of movements as a communist, and for the rights of Koreans in Japan, especially from the viewpoint of those who aligned themselves with DPRK, and in such regard he opposed the talks in the early 1960s that led to the normalization of relations between Japan and ROK in 1965. In the early 1970s, while backing Pak Chong Sok, Satō became disillusioned with both DPRK and communism. He was especially unhappy with reports regarding DPRK's treatment of some of the so-called returnees, and by the attitudes of DPRK-aligned Koreans in Japan toward Pak, who at the time his case went to trial was still distancing himself from a Korean identification, which had been alien to him. Satō began leading the Chōsen Kenkyūjo in a direction that opposed DPRK, and became the institute's head in 1983. The following year it became Gendai Koria Kenkyūjo (現代コリア研究所) or "Gendai Korea Research Institute" and the jounral was renamed Gendai Koria (現代コリア) or "Gendai Korea". The journal ceased as a paper publication in 2007, but as of this writing (February 2011) its name continues to inspire Satōs gendaikorea.com website. By the mid 1980s, Satō had left JCP and begun supporting people with grievances against DPRK. Since the late 1990s, he has been especially active on behalf of families of people abducted by DPRK agents. Satō also busies himself writing about the current conflicts involving DPRK, and perhaps as a gesture of hope that ROK and DPRK can overcome their differences, the splash page of his website shows updated reports on weather conditions in Seoul in the "Dai Kan Min Koku" (ROK) and Pyongyang in "Kita North Chōsen" (DPRK). Top?? |

De Vos and Chung 1981Lee_De_Vos_1981_Koreans_in_Japan_000_yb_150.jpg Lee_De_Vos_1981_Koreans_in_Japan_000f_yb_150.jpg Lee_De_Vos_1981_Koreans_in_Japan_000iii_yb_150.jpg Lee_De_Vos_1981_Koreans_in_Japan_000v_yb_150.jpg Lee_De_Vos_1981_Koreans_in_Japan_000vi_yb_150.jpg Lee_De_Vos_1981_Koreans_in_Japan_000vii_yb_150.jpg Lee_De_Vos_1981_Koreans_in_Japan_000x_yb_150.jpg Lee_De_Vos_1981_Koreans_in_Japan_225_Chung_yb_150.jpg Lee_De_Vos_1981_Koreans_in_Japan_281_Wetherall_yb_150.jpg "Community Life in a Korean Ghetto"Changsoo Lee and George De Vos (editors)

with contributions by Daekyun Chung,

Thomas Rohlen, Yuzura [sic Yuzuru] Sasaki,

Hiroshi Wagatsuma, and William O. Wetherall

For a bibliographies/Bibliography_minorities.html#lee1981 This book, as of the time of this writing (2024), is nearly four decades old as a publication, and half a century old as a concept. Of the book's 15 articles, Chongsoo Lee was an author of 10 -- 6 solo, one as the primary author with George De Vos, and 3 as the secondary author with De Vos. The other 5 contributions were by 6 authors, one by George A. De Vos with Daekyun Chung. 6 Changsoo Lee 1 Changsoo Lee and George De Vos 3 George De Vos and Chongsoo Lee 1 George De Vos and Daekyun Chung 1 Hiroshi Wagatsuma 1 Yuzuru Sasaki and Hiroshi Wagatsuma 1 Thomas Rohlen 1 William O. Wetherall Forthcoming. |

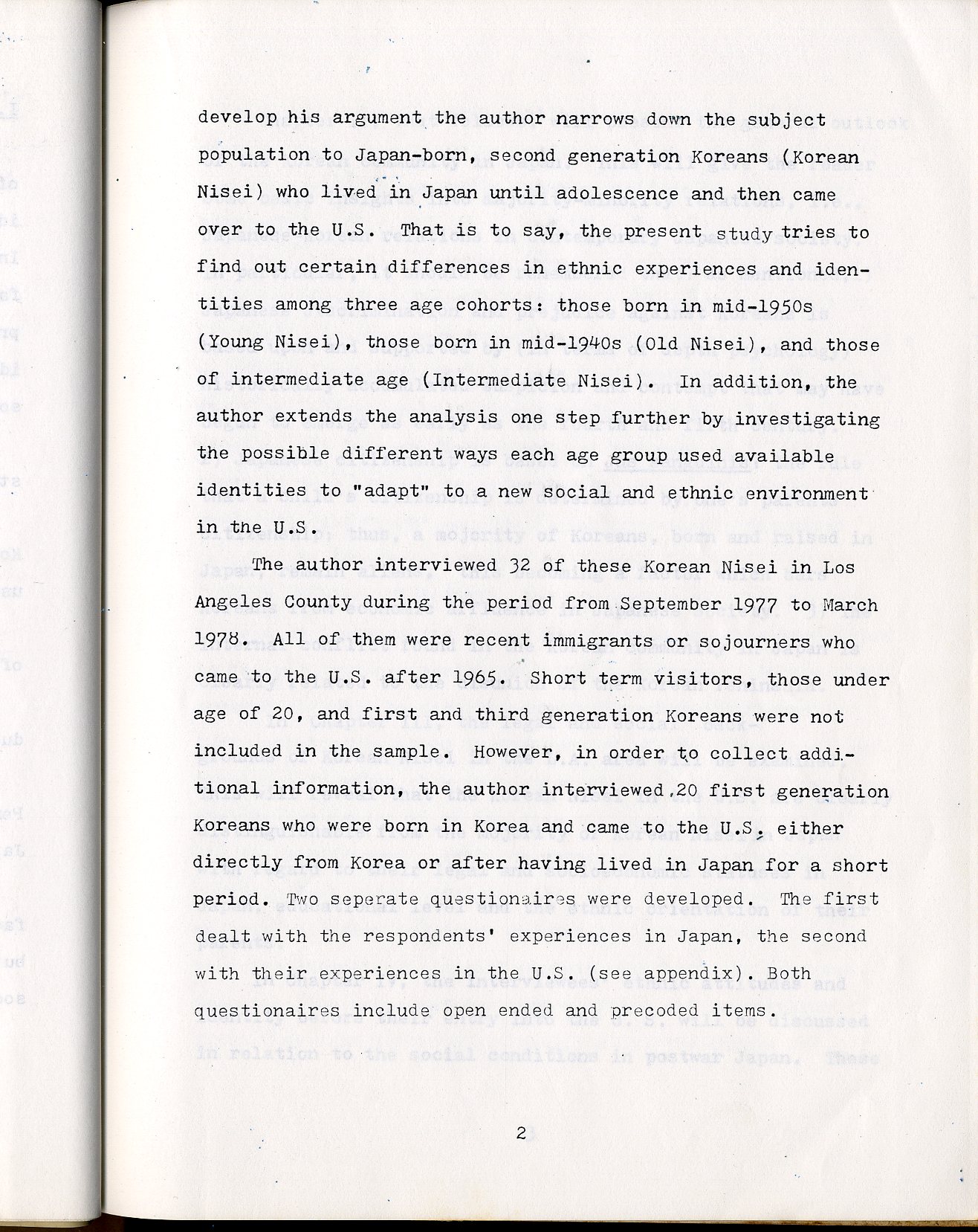

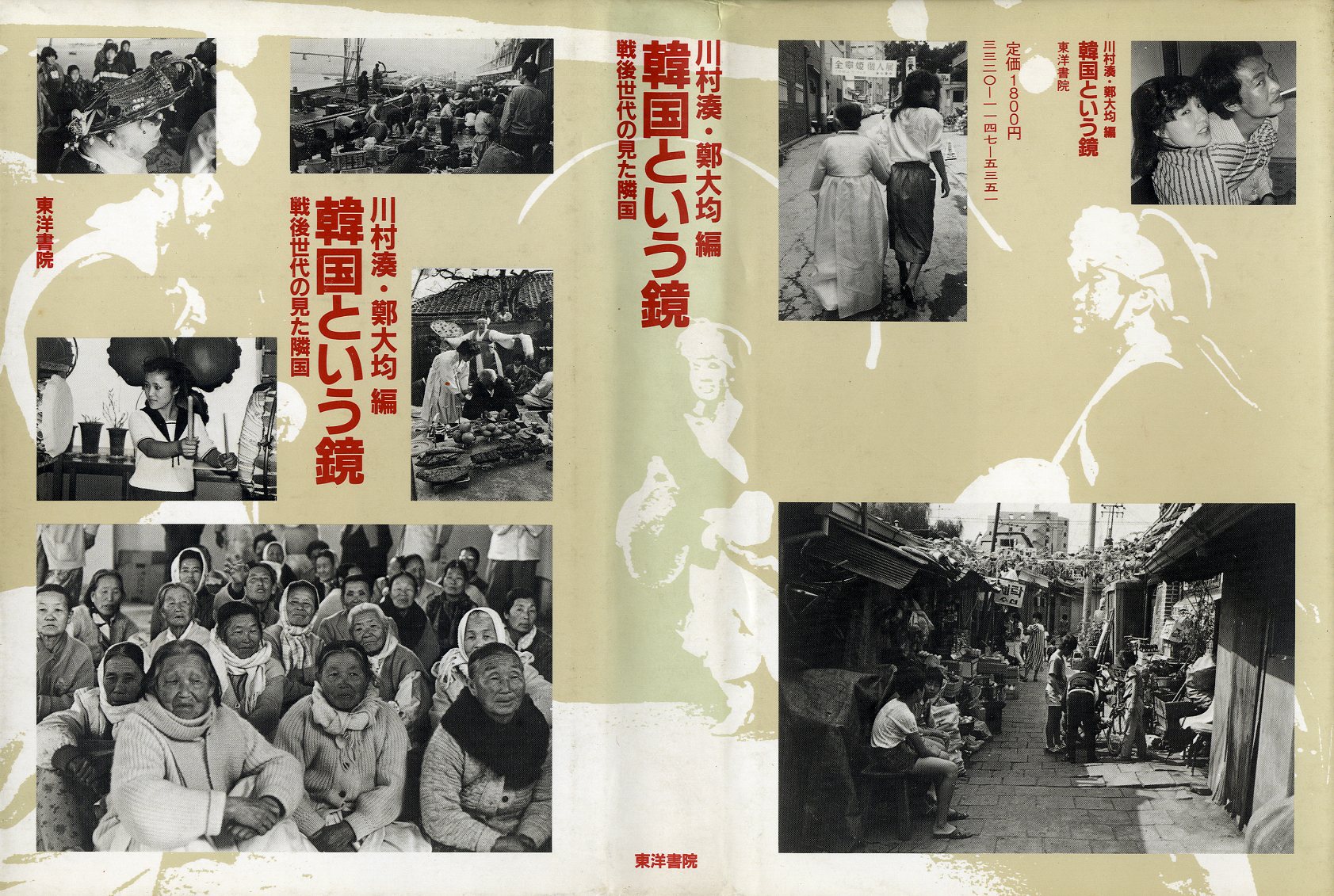

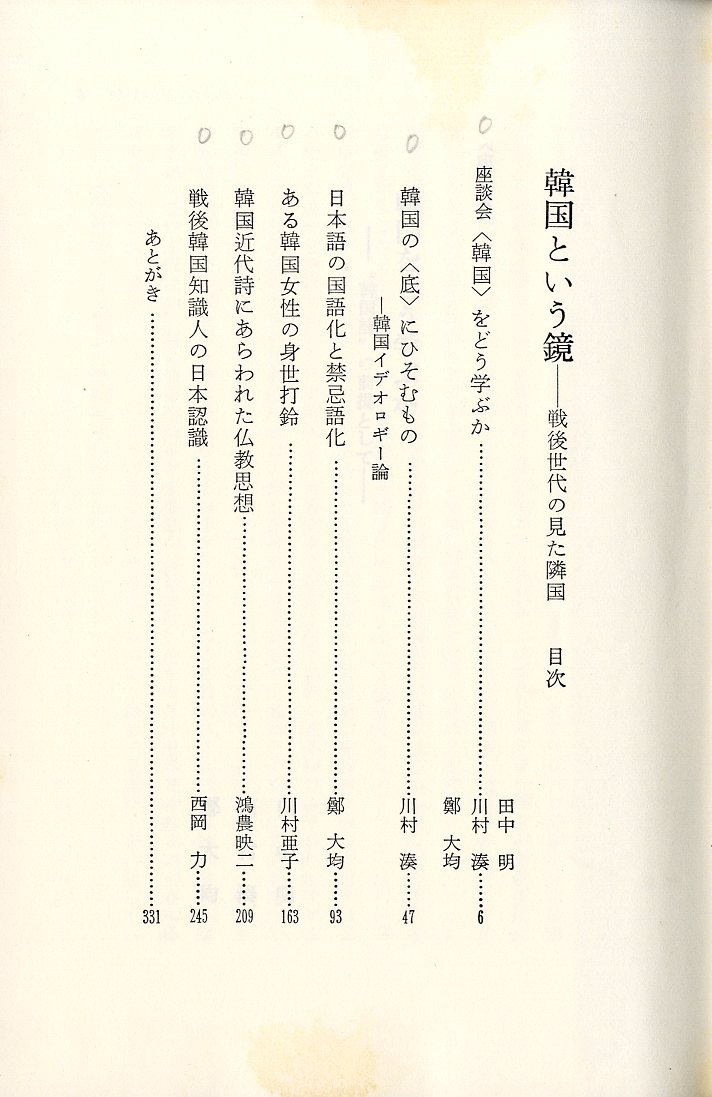

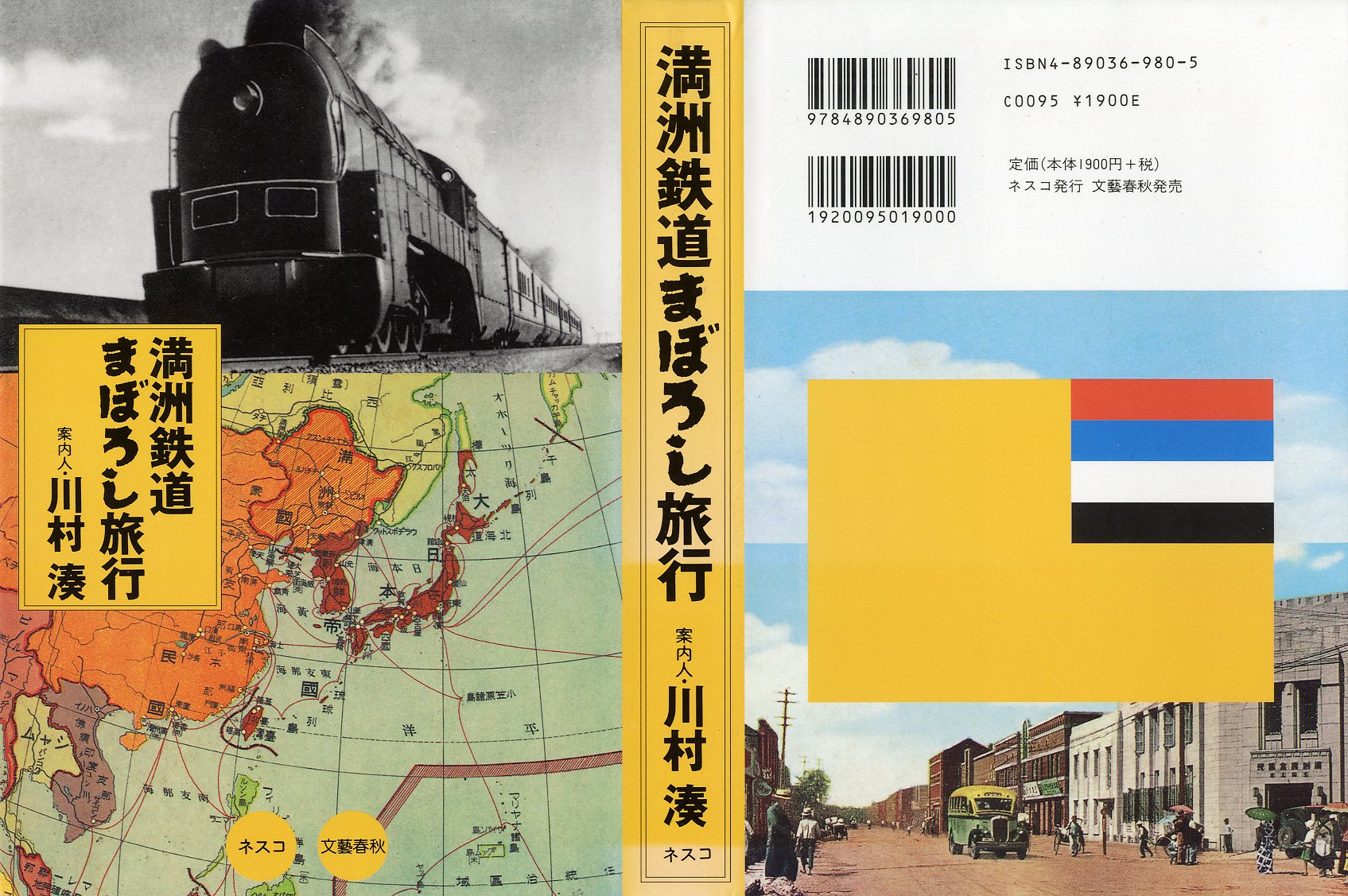

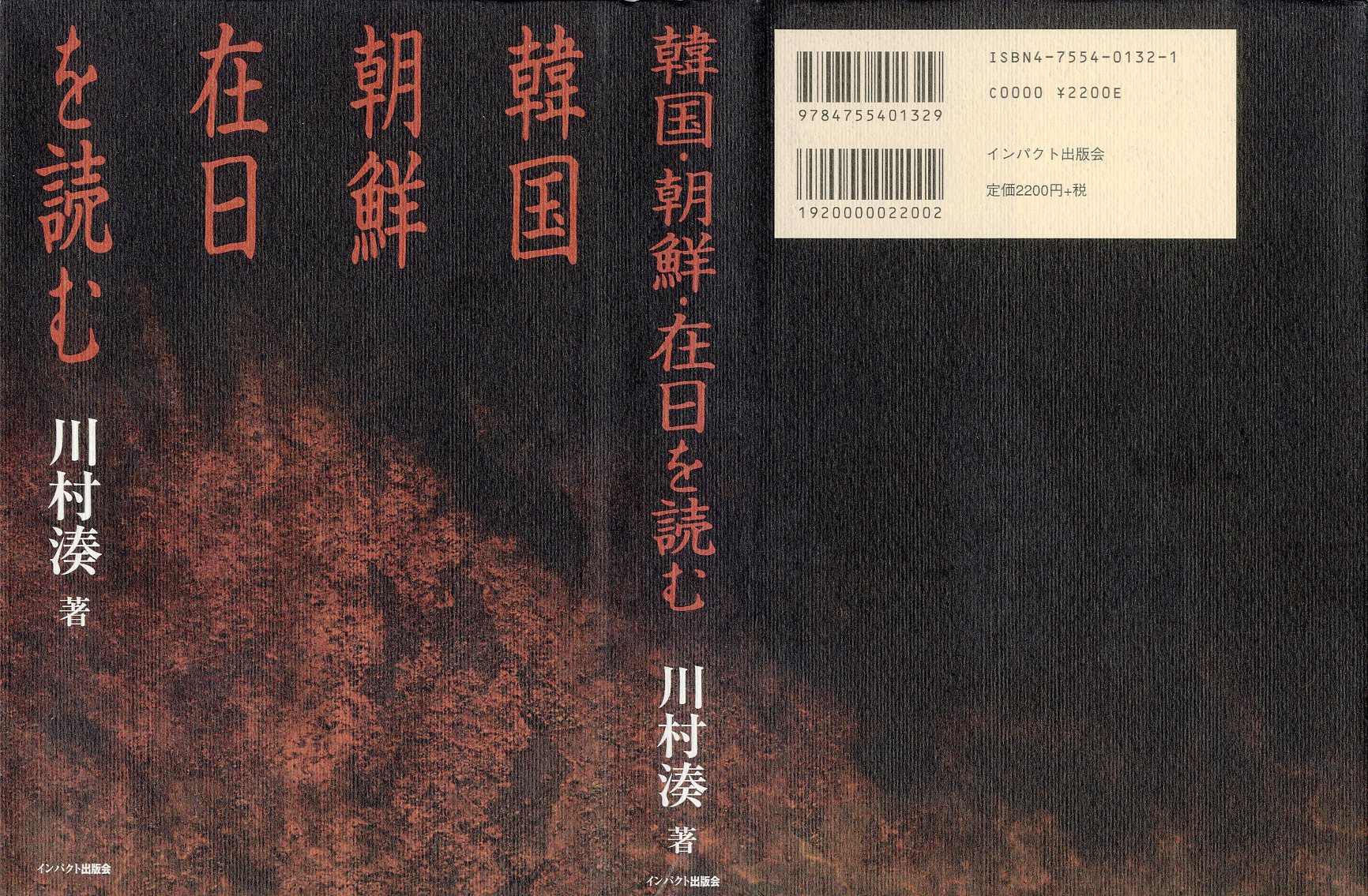

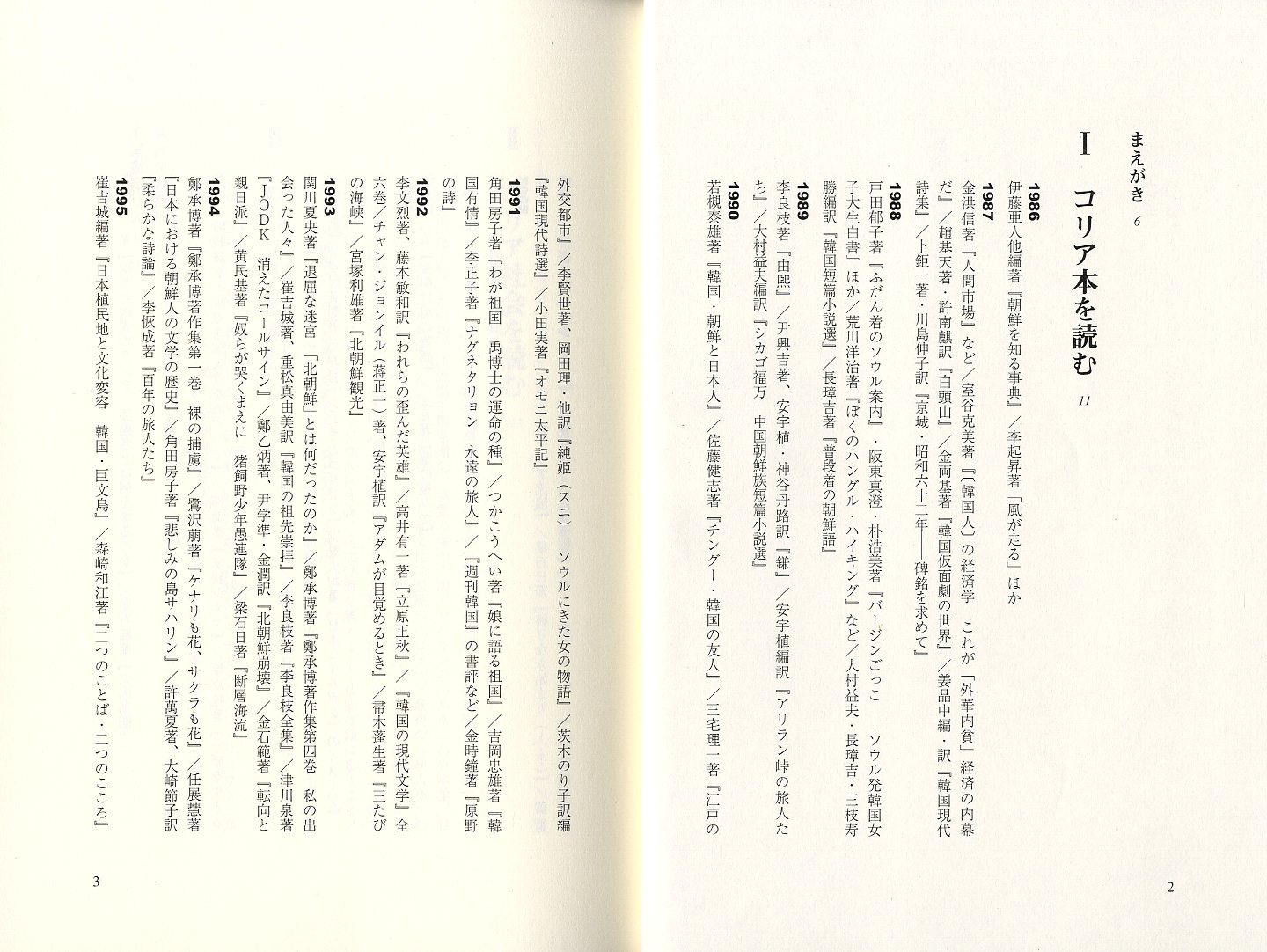

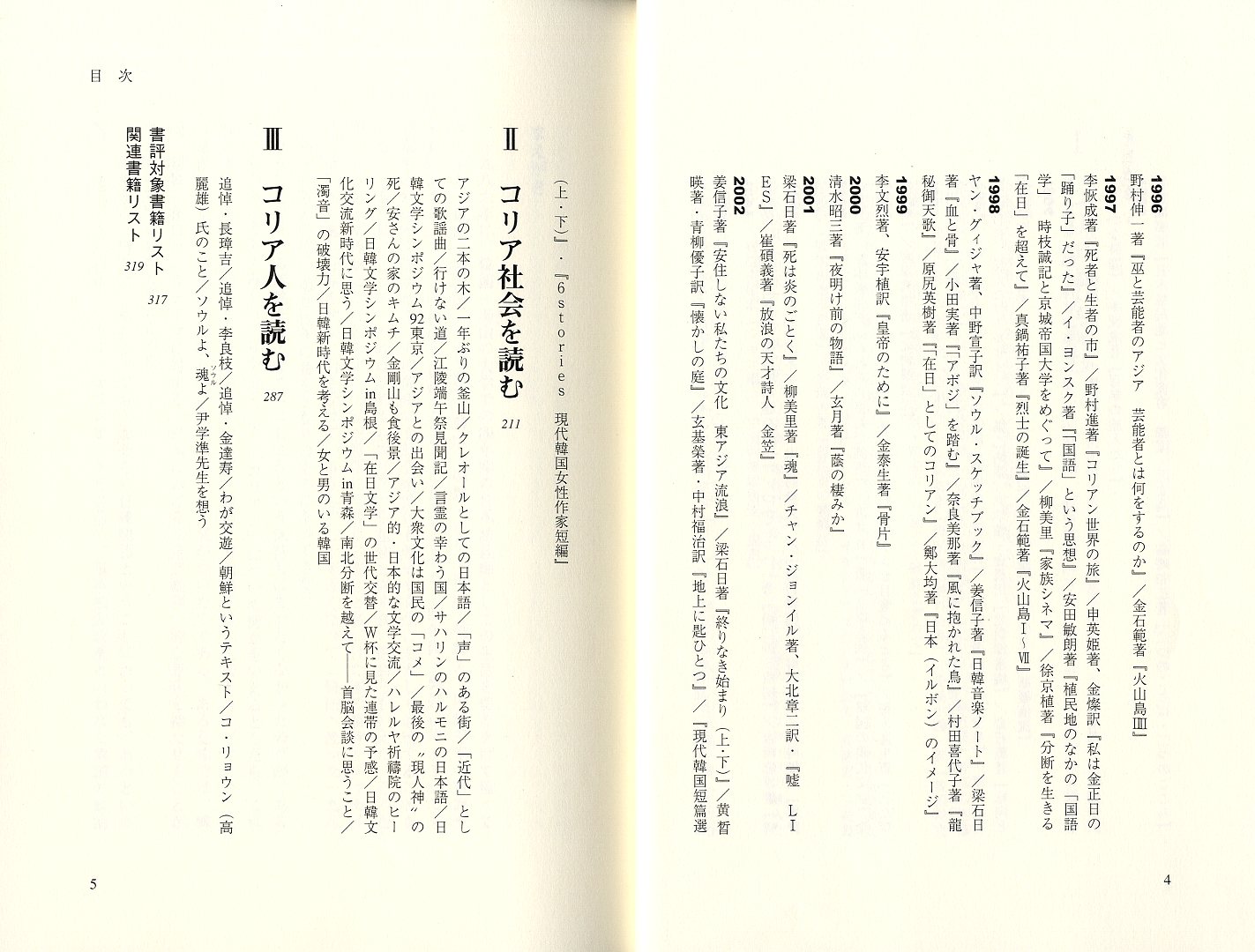

Kawamura and Chung 1986川村湊、鄭大均 (チョン テギュン)、編 Kawamura Minato and Chung Daekyun (Chon Tegyun), editors The cover, spine, title page, and colophon list Kawamura and Chung as the editors. There contents page lists 6 articles and an afterword -- actually two afterwords (atogaki あとがき), both 2-pages each, the first by Chung (331-332), the second by Kawamura (333-334). The biographical profiles on the colophon list the following contributors (romanizations of names mine). Kawamura Minato 川村湊 b1951 Chun Degyun [Chung Daegyun] 鄭大均 b1948 Tanaka Akira 田中明 b1926 Kawamura Ako 川村亜子 b1951 Kōno Eiji 鴻農英二 b1952 Nishioka Tsutomu 西岡力 b1956 Kawamura Minato and Chung Daegyun were both, then, lecturers in the Japanese language and literature department at Tong-A University (東亜大学校) in Pusan (釜山). Kawamura's wife Ako had also been a lecturer in the same department. Tanaka, whose thinking would greatly influence Chung, was a Korea and Chōsen specialist and professor at the Institute of World Studies (海外事情研究所 "Foreign Affairs Institute") of Takushoku University (拓殖大学) in Tokyo. Kōno had been a Japanese language teacher at Sangmyung [Sangmyŏng] Women's College in Ch'ŏnan (Cheonan) in Korea, and in 1982 he and others had translated a collection of poems by Sŏ Chŏju (徐廷柱 1915-2000). Nishioka, formerly a researcher at the Japanese embassy in Seoul, would go on to be a very writer of magazine articles and books on controversial issues related to historical and present-day Korea and Chōsen. All contributors except Tanaka were born within a decade or so after the Pacific War. And all except Chung were Japanese nationals. But Chung, like the other contributors, was born, raised, and educated in Japan, and his native language was Japanese. Minimalizing Japanese language influences on KoreanFor my purposes, Chung's article is on "The national-language-ization and forbidden-language-ization of the Japanese language" in Korea -- the longest in the book -- is the most interesting. 鄭大均 Chung Daegyun [ Korea as a mirror] ] Tokyo: Tōyō Shoin, 1986年 Pages 93-161 After returning to Japan from UCLA in 1979, Chung taught Japanese for a while at a language school in Yotsuya in the center of Tokyo. Japanese was literally his mother tongue, but his nationality and name generally suggested that he was not Japanese. Chung's students seem to have liked him, perhaps better than most of their teachers, because he was street smart. He was able to give them a "foreigner's" perspective on survival in Japan, having grown up in Japan as a "gaikokujin" (外国人) or "outlander" -- and having recently lived in the United States as a foreign student, speaking English as a second language, and occassionally having to deal with unwanted treatment if not hostility. However, an administrator of PL, the language chainwho felt that teachers of Japanese at the school should be Japanese, made life uncomfortable to Chung, and he took his teaching talents to Korea, determined to master his father tongue, which he had heard growing up, but spoke very little. Kawamura 1998川村湊 (案内人) Kawamura Minato (annaijin) [guide] Kawamura 2003川村湊 Kawamura Minato |

||||||||||||||||

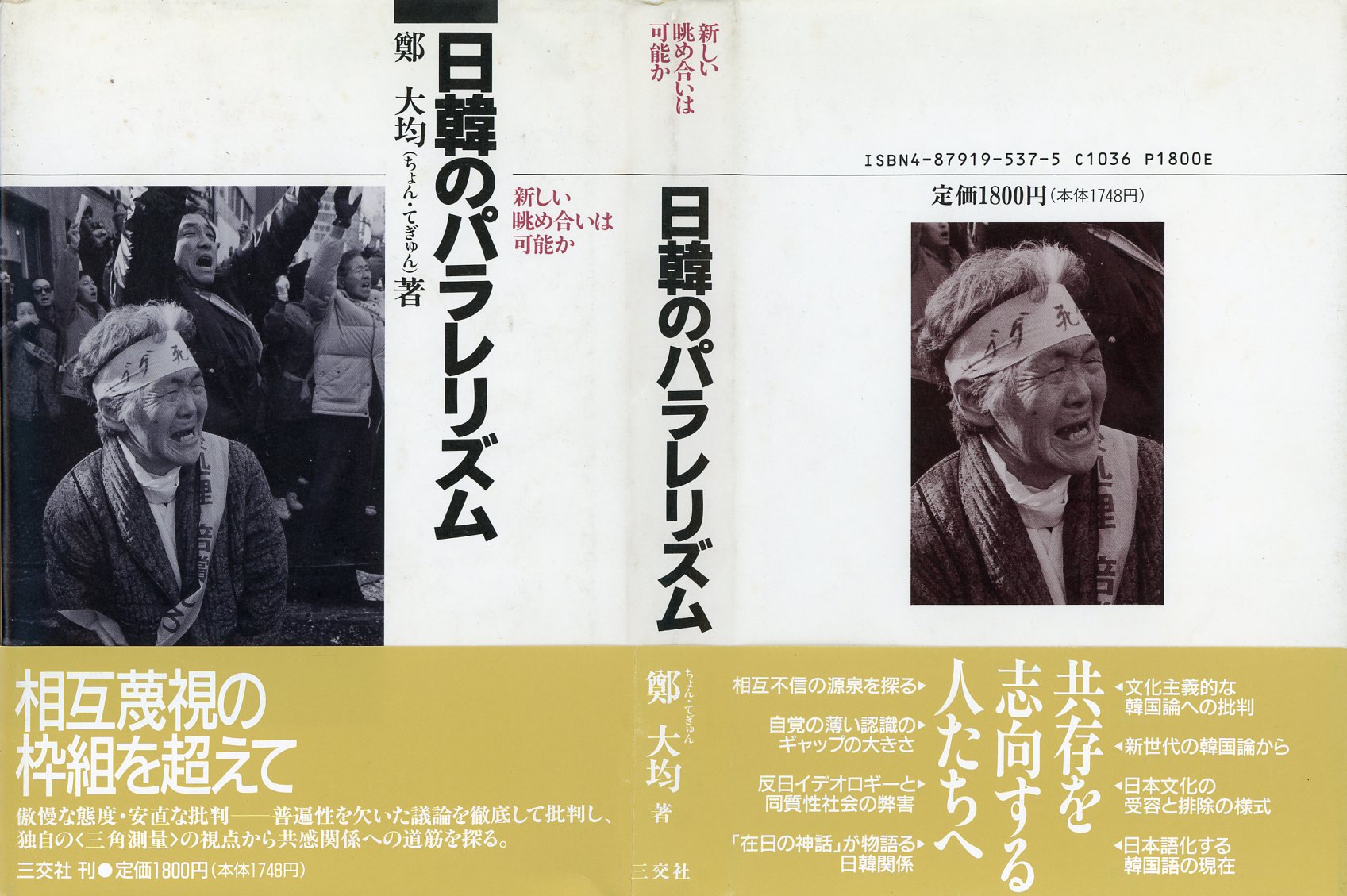

Chung 1992鄭大均 (ちょん・てぎゅん Chon Tegyun (© Chung Daekyun) This book was republished in a substantially revised edition in 2003 as Kankoku no nashonarizumu (韓国のナショナリズム) [Nationalism of Korea (ROK)] by Iwanami Shoten. See Tei (Chung) 2003 below for details. |

Tei (Chung) 1995, 2010鄭大均 (てい・たいきん Chung, Daekyun) Tei Taikin (Chung Daekyun) An expanded and updated edition of this book was published in 2010 (see below). |

Tei (Chung) 1998鄭大均 (てい・たいきん Chung, Daekyun) Tei Taikin (Chung Daekyun) |

Tei (Chung) 2001鄭大均 (てい たいきん Chung Daekyun) Tei Taikin (Chung Daekyun, © Tei Taikin) This is Tei's first book-length examination of the status and conditions of Koreans in Japan. As its title words "Zainichi" and "Kankokujin" signify in his usage, the book addresses mainly issues concerning aliens in Japan who are nationals of the Republic of Korea who qualify as Special Permanent Residents (SPRs). SPRs constitute a shrinking caste, or descent group, of aliens domiciled in Japan. The progenitors of the group were the Taiwanese and Chosenese who were residing in Japan's prefecutral Interior on 2 September 1945 when Japan surrendered to the Allied Powers, ending World War II, and who remained in the prefectures. Only lineal descendants are born, raised, and remain in the prefectures qualify as members. And because for many years now, the death and naturalization rates have exceeded birth rates, the SPR caste is rapidly shrinking and will be all but extinct by the middle of the 21st century. The terms of surrender signed on 2 September 1945 included the loss of Chōsen and Taiwan as parts of Japan. On this date, Japan provisionally lost own sovereignty, including its sovereignty over Chōsen and Taiwan. And it lost its control and jurisdiction over these territories when surrendering the northern part of Chōsen to USSR forces on , the southern part to US forces on 8 September 1945, and Taiwan to ROC forces surrendering Taiwan to ROC forces on 25 October 1945. Sovereignty was formally lost on 28 April 1952 when terms of the San Francisco Peace Treaty came into effect. provisionally lost its sovereignty, and control anAnd because Japanese nationality is territorial, the separation of Taiwan and Chōsen from Japan meant the separation of Taiwanese and Chosenese from Japan's nationality.On Taiwanese and Chosenese lost Japan's nationality on 28 April 1952 on account of Japan's loss of Taiwan and Chōsen, and (2) their lineal descendants, whether (a) those who were born and remained in the prefectures as Japanese between 3 September 1945 and 28 April 1952 and also lost Japan's nationality, or or those who were born aliens in Japan on or after 29 April 1952. Residentially qualified Taiwanese and Chosenese who lost Japan's nationality on 28 April 1952 acquired a special "Potsdam law" status called 126-2-6, which permitted them to reside in Japan indefinitely without acquiring a status of residence under the Immigration [Exit-enter-country] Control Law. Those born aliens during later years received various statuses created for their circumstances as descendants of 126-2-6 aliens. In 1991, all statuses that stemmed from the loss of Japan's nationality in 1952 were consolidated under the present Special Permanent Resident status. SPR, like 126-2-6 and the Agreement Permanent Residence status that began in 1966 for qualified Chosenese who migrated to ROK nationality, is not part of the Immigration [Exit-entry-country] Control Law, which defines both visa and non-visa statuses for aliens permitted to reside in Japan, but is directly linked with postwar settlements. The formal name of the SPR law is "Special law concerning, inter alia, immigration [exit-enter-country] control of persons who based on the Treaty of Peace with Japan separated from the nationality of Japan". However, (1) Taiwanese and Chosenese residing in Japan's prefectures, who had been residing there from on or before 2 September 1952 when Japan surrendered, and (2) descendants born in the prefectures on or after 29 September 1945, if they remained in the prefectures , lost Japan's nationality on 28 April 1952. These nationality losers who qualified as members of the , and they became aliens with a special status accorded them under a so-called "Potsdam law". "Potsdam" alludes to 1945 Potsdam Declaration, which incorporated the terms of 1943 Cairo Declaration, which stated that "Formosa and the Pescadores" (Taiwan) would be "restored to the Republic of China", and "Korea" (Chōsen) would "in due course . . . become free and independent." Potsdam laws implemented actions that complied with enforcement of the terms of surrender. One such action was Civil Affairs A No. 438 notification on 19 April 1952, which stated that, Taiwan and Chōsen would be separated from Japan pursuant to the terms of the Peace Treaty, which would go into effect 9 days later, Taiwanese and Chosenese would be separated from Japan's nationality. A Potsdam law then defined a special status for nationality losers who had been residing in Japan since the end of the war or were born in Japan after the war born to suchto . would eventually be restablished as a sovereign state.and "Korea" (Chōsen would be on 28 April 1952 when Japan lost Taiwan and Chōsen under the terms of the San Francisco Peace Treaty. The treaty reflected the terms of surrender it accepted on 2 September 1945, which in turn reflected stipulations in the 1943 Cairo Declaration and the 1945 Yalta Agreement. The SPR status, created in agreement that concomitant pursuant to the terms of the formally abandoned . The status is not defined by the nationality of the alien but by whether the alien had become an alien by losing was ha (1) legally residing in Japan's prefectures on 2 September 1945 as a national of Japan and remained in the prefectures, (2) was born tolost Japan's nationality on 2 28 April 1952, or (4) was born in the prefectures Japanwas once Japanese The caste originated on 2 September 1945 are aliens defined by their the historical loss of Japan's nationality represent about 50 nationalities. Most are nationals of Kankoku. Some are deemed nationals of Chōsen, now a legal fiction, the ghost of Japan's former territory of Chōsen, which is still an entity in Japanese law. A few are nationals of the Republic of China, or the People's Republic of China, and others are spread across the rest of the nationality spectrum.SPRs status, however, is not defined by Note that while most SPRs are Koreans in Japan, most Koreans in Japan not SPRs. SPRs are aliens whose status of residence in Japan derives from membership in a caste whose loss of Japan's nationality concomitant with Japan's loss of Taiwan and Chōsen under the terms of the San Francisco Peace Treaty, effective from 28 April 1945. , reflectinunder the of general surrender agreed to on 2 September 1945, which were reflected in the San Francisco Peace Treaty, signed on 9 September 1951 and effective from 28 April 1952. from post World War II settlements territorial settlements that caused the progenitors of the SPR population to lose Japan's nationality defined their loss of Japan's nationality orby membership in a population that originated in Occupied Japan on 2 September 1945, from the Taiwanese and Chosenese who were then residing in the prefectures and remained, and from their prefecture-born descendants who remained. SPRs constitute a caste because dmembership is a matter of lineagedefined by 2 qualities -- (2) It is, in the prefectures.prefecturalInterior. the form of residents (1) separation from Japan's nationality through effects of the San Francisco Peace Treaty on 28 April 1952, and (2) continuous residence in Japan's prefectures . SPRs are either people who themselves lost Japan's nationality on this date, or who were born in Japan after this date as the lineal descendant of a nationality loser. Intheir birth in Japan on or after 29 April 1952 as a lineal descendant of someone who lost Japan's nationality on 28 April 1952this date -- provided that they were residing in Japan's prefectures on or before 2 September 1945 and have remained continusouly domiciled in Japan, or have continuousy resided in Japan since their birth in Japan on or after 31945Japan's prefectures. a nationality loser. the day Japan surrendered to the Allied Powers, ending World War II, and remained in Occupied Japan, and their descendants born in Japan's prefectures on or after 29 September 1945, and who lost Japan's nationality from the effects of the San Francisco Peace Treaty on 28 April 1952, and (2) descendants of such nationality losers who were born in Japan on or after 29 April 1952 and remained continuously domiciled in Japan (3), and (4) became nationals of the Republic of Korea when it became possible to do so their descendants born and continuously domiciled in Japan on or after 29 April 1952, and (4) are registered in Japan as aliens of Republic of Korean nationality. RESUME The maintenance of Korean nationality into second, third, and later generations is partly an anomaly of both Japan's and ROK's nationality laws. But it also reflects an attitude toward nationality that doesn't make sense in light of the fact that most Koreans in Japan are so totally integrated into Japan's mainstream that it makes no point not to be Japanese.The title reflects Francis Fukuyama's "The End of History and the Last Man" (1992). The number of Koreans in Japan who are categorically "Zainichi Kankokujin" -- by virtue of their treaty-accorded "special permanent residence" status -- is rapidly shrinking through death and naturalization, and the fact that most Koreans marry Japanese and their children are able to acquire Japanese nationality at time of birth. So it is only a matter of time before there will be no significant population of such what I call "legacy Koreans" in Japan. |

Tei (Chung) 2002鄭大均 (てい たいきん Chung Daekyun) Tei Taikin (Tei Taikin, Chung Daekyun, © Chung Daekyun) |

Tei (Chung) 2003鄭大均 (てい たいきん Chung Daekyun) Tei Taikin (Tei Taikin, Chung Daekyun, © Taikin Tei) This book is a substantially revised edition of Nikkan no pararerizumu (日韓のパラレリズム) [Parallelism of Japan and Korea (ROK)], published in 1992 by Sankōsha. See Chung 1992 for details. |

Tei (Chung) 2004鄭大均 (てい たいきん Chung Daekyun) Tei Taikin (Chung Daekyun, © Tei Taikin) Over the past two or three decades, a number of researchers have debunked the myth -- commonly reported as fact in mass media and books in Japanese and English -- that Koreans in Japan are the descendants of colonial subjects forcefully brought to Japan to work. Tei, however, has written -- if not the last word on the subject -- the most important overview to date. |

Chong Hyang Gyun 2006鄭 香 均 (チョン ヒャン ギュン) (編集者) Chon Hyan Gyun [Chong Hyang Gyun] (editor) Chong Hyang Gyun (鄭香均 1950-2019) was and still is Tei Taikin's sister. Chong was a public health nurse, employed as a civil servant by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government. Her experience and ratings qualified her for a managerial position, so in 1994 she applied to take the required qualification exam. However, she was not allowed to take it on account of her nationality. A prefectural ordinance required that managerial civil servants be Japanese nationals, and Chong was a national of the Republic of Korea. Chong was born in 1950 with three civil statuses -- Japanese by nationality, Chosenese by territoriality, and a deemed alien. The latter status was a legal fiction created by the Japanese government, under the direction of GHQ/SCAP, to facilitate the foreseen loss of Japanese nationality by Taiwanese and Chosenese, hence the decision to treat those then residing in the occupied prefectures as aliens for the purposes of border control and residence registration. For all other purposes, they were Japanese with register domiciles in the non-prefectural territories of Chōsen and Taiwan.

Japan had surrendered Chōsen south of the 38th parallel of latitude to military commanders of the United States, and north of the 38th parallel to military commanders of the Soviet Union, in September 1945. The US and USSR proceeded to occupy their respective halves of the peninsula and create new governments in 1948, the Republic of Korea in the south and the Democratic Republic of Korea (Chosen) in the north. Taiwan was surrendered in December 1945 to military commanders of the Republic of China, which made the territory a province and began to nationalize its people. While Japan unconditionally surrendered to the Allied Powers in September 1945 with the understanding that it would lose Taiwan and Chōsen -- and while in fact Japan formally surrendered its control and jurisdiction over these territories after its general surrender to the Allied Powers -- the formal relinquishment of all claims and interests in Taiwan and Chōsen would not be finally confirmed until relevant terms in a peace treaty came into effect -- and that would not happen until 1952. Until then, under Japanese law and Allied Occupation law -- and under international law to the extent that it recognized the primacy of the effects of Japanese law under the effects of Allied Occupation law during the period that Japan was occupied and its sovereignty in the hands of the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers -- Taiwanese and Chosenese in the occupied prefectures would remain Japanese. In 1952, when the terms of the San Francisco Peace Treaty came into effect, and Japan formally lost Taiwan and Chōsen, it also lost the territorial foundation for attributing its nationality to people in Taiwan and Chōsen domicile registers. Accordingly, Chong Hyang Gyun -- her father and mother, and older brothers, including Tei Taikin -- lost Japan's nationality and became aliens of Chōsen nationality. The only problem was that Chōsen was not a state. The peninsular territory, once liberated, was supposed to be restored to Korean statehood. Instead, it was divided into two occupation zones that became the homes of two states, which were then at war, both claiming to be the sole legitimate government on the peninsula. ROC, as a member of the Allied Power, was allowed to enroll Taiwanese in Occupied Japan into its nationality. And by 1952, most Taiwanese in Japan had become ROC nationals and in effect abandoned their Japanese status. When Korea became the Japanese territory of Chōsen in 1910, Korea ceased to exist as a state in both Japanese and international law. So there was no Korean state in 1945 to receive Japan's surrender. And neither ROK nor DPRK, established in 1948, qualified as an Allied Power, though both ideologically insisted they were formed on foundations of resistance to Japan both before and during the Pacific War. In any event, ROK was not allowed to enroll Chosenese in Japan in its nationality until Japan and ROK normalized their relationship with a basic treaty, which would not be signed and ratified until 1965. A status agreement providing for the treatment of ROK nationals in Japan, also signed and ratified in 1965, came into effect from 1966, hence from that year it became possible for Chong and other Chosenese to apply for ROK nationality. Some Chosenese in Japan align themselves with DPRK. And over the decades, some DPRK-aligned Chosenese in Japan have managed to obtain DPRK passports or equivalent proof of possessing DPRK nationality. But as I write this today (2024), Japan and DPRK have yet to normalized their relationship, much less signed and ratified a status agreement. And Japan has no legal grounds for recognizing DPRK nationality. Not that this would have mattered for Chong or other members of her family, all of whom became ROK nationals. Chong's father returned to the peninsula and died there. Her oldest older brother was still Korean when he died. Chong seems to have had no desire to naturalize -- unlike her mother and younger older brother. Chong Hyang Gyun strongly disagreed with the conclusion of the Supreme Court that limiting some jobs Japanese nationals was, as a general principle of nationality, a matter of course. That is, after all, the purpose of nationality -- to differentiate, i.e., discriminate, people on the basis of their formal state affiliation. And every sovereign state has an absolute right to determine both who it regards as its subjects, nationals, or citizens -- and which aliens it permits to enter or live in the country, and the terms of their stays. For images, particulars, and comments about her book -- with an overview of her pursuit of justice in the Tokyo District Court (lost), Tokyo High Court (won), and Supreme Court (lost) -- see Chong v Tokyo, 2005: Not allowing aliens to hold civil service posts is not unconstitutional under "Aliens and the Constitution" in the "Elements of citizenship" section of this website. |

||

Tei 2006鄭大均 (てい・たいきん) Tei Taikin (© Taikin TEI) This is a very moving book, in which Tei -- born in 1948 during the Allied Occupation of Japan -- shares many personal and frank thoughts about his father (born in Korea in 1899), his mother (born in Iwate prefecture in 1909), his older brother (born in Tokyo in 1944), and his younger sister (born in Iwate in 1950). He also revels a great deal about himself as he grew up and forged his own way in life, and as his experiences changed his perceptions of the world, who he was, and what he wanted to be. In the penultimate chapter, Tei talks very candidly about his sister's law suit against the Tokyo Metropolitan Government (see review of Chong Hyang Gyun 2006). For the record, he was opposed to the suit. His arguments are at once powerful and, in view of how he phrases his criticism of his own sister, very poignant. For a review of Chong Hyang Gyun's court case and book, see Chong v Tokyo, 2005 under "Aliens and the Constitution" in the "Elements of citizenship" section. In the final chapter, Tei narrates his own journey back to Japanese nationality through naturalization. In an earlier chapter he also talks about his mother's naturalization in 1985. When she married his father, she moved from her Interior (Naichi 内地) family register in Iwate prefecture to his register in Chōsen (Chōsen), a separate legal territory of Japan. So Tei's mother, as a former Interiorite in a Chōsen territorial register, also lost Japanese nationality as a result of the effect of territorial settlements in the 8 September 1951 San Francisco Peace Treaty, effective from 28 April 1952. Tei's "lightness of being" title is inspired by Sonzai no taerarenai karusa -- the Japanese title of Milan Kundera's The Unbearable Lightness of Being (1985). The Czech title is Nesnesitelna lehkost byti (1982, 1984), but the novel could not be published in Czechoslovakia, and apparently Kundera has not allowed it to be published in the Czech Republic. |

Tei and Furuta 2006鄭大均 (てい たいきん)、古田博司 (ふるた ひろし) (編) Tei Taikin and Furuta Hiroshi, editors (© TEI Taikin, FURUTA Hiroshi) This book contains a general roundtable discussion between three commentators, and thirty shorter standalone articles about specific issues that reflect the shared view of the contributors that both the Republic of Korea (ROK, Korea) and the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK, North Korea) are engaged in spreading falsehoods about the past, especially regarding Japan and its treatment of Korea and Koreans. All the articles are titled according the formula "If you're told 'Falsehood'" (「嘘」と言われたら "Uso" to iwaretara). Tei wrote the foreword and an article entitled "If you're told "Koreans in Japan are decesdants of '[people] forcibly brought [to Japan]'" (「在日コレアンは『強制連行』の子孫だ "Zainichi Korean wa 'kyōsei renkō' no shison da' to iwaretara). Furuta wrote the postscript and participated in the roundtable discussion on the "Mental structure of Korean and North Korean 'self-absolutism'". All the favorite claims by historians and others who fall in step with the victimhood school that drives Korean ethnonationalism are addressed here. Here is a sample of other claims every bit as contentious as the "forcibly brought" claim countered by Tei Taikin. Tanaka Akira Harada Tamaki Nagashima Hiroki Araki Nobuko Nishioka Tsutomu Tamaki Motoi Asakawa Akihiro Tei Taikin Harada Tamaki |

Tei 2010鄭大均 (てい・たいきん Tei Taikin (© Taikin TEI) Forthcoming. |

Kobayashi 2011Tei Taikin is featured with five other "new Japanese" who became Japanese through naturalization, in the following collection of in-depth discussions with Kobayashi Yoshinori, the creator of the "gomanism" manga series. 小林よしのり Kobayashi Yoshinori Kobayashi's purpose, in addition to drawing out why the discussants wanted to be Japanese, is to disseminate their opinions about all manner of issues involving Japan, including the issue of whether nationality should be a requisite for political participation. See Kobayashi 2011 in the Bibliographies section for details. The six discussants are as follows. 石 平 せき へい Seki Hei [Seki Hei] 1962 born in PRC 1988 came to Japan 2007 naturalized 呉 善花 お そんふぁ O Sonfa [O Son Fa] 1956 born in ROK 1983 came to Japan 2005 naturalized 鄭 大均 てい たいきん Tei Taikin [Tei Taikin] 1948 born in Japan 2004 naturalized ペマ・ギャルポ Pema Gyarupo [Pema Gyalpo] 1953 born in Tibet 1965 came to Japan 2005 naturalized ビル・トッテン Biru Totten [Bill Totten] 1941 born in the United States 1969 came to Japan 2006 naturalized 金 美齢 きん びれい Kin Birei [Kin Birei] 1934 born in Taiwan [then part of Japan] 1959 came to Japan 2009 naturalized Each of the six was born in a different county. Only Tei Taikin was born in Japan, And only Tei and Kin Birei, who was born Taiwan, were Japanese nationals from their time of their birth to 1952, when Japan formally lost Chōsen and Taiwan as integral parts of its sovereign dominion, which meant that people in Chōsen and Taiwan lost Japan's nationality -- an artifact of territorial affiliation with Japan. To be continued. |

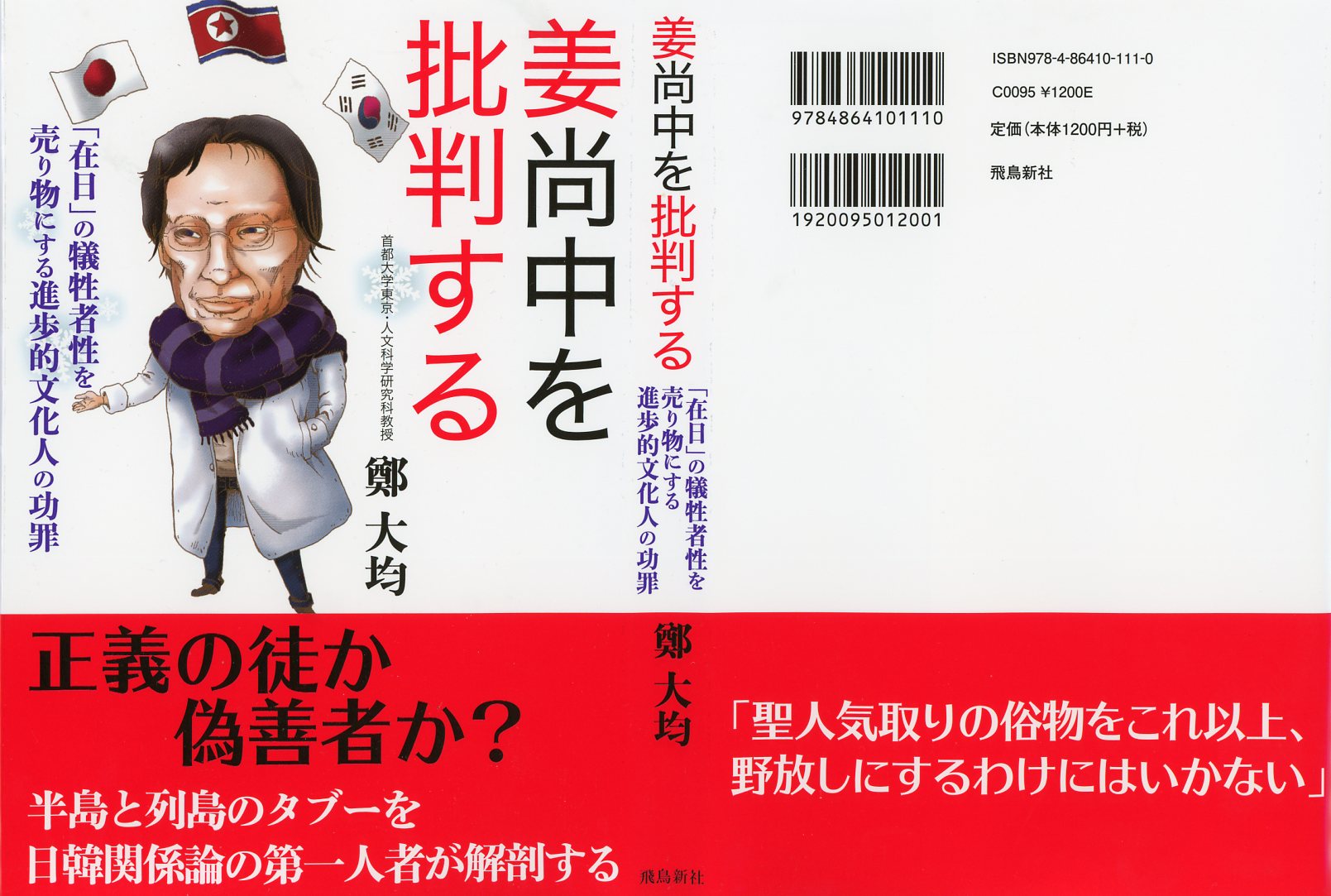

Tei 2011鄭大均 (てい・たいきん Tei Taikin (© Taikin TEI) Forthcoming. 「カン様」の語る、在日の犠牲者性は自明か? 在日の帰化が未だにタブーとされる不自然さと、「在日=犠牲者」図式に潜むレイシズムを、日韓関係論の第一人者が鋭く告発。南北統一幻想と半島政治に翻弄される「ペーパー外国人」の不幸から脱却する道を説く。 (目次より) ・矮小化される苦難の歴史 ・在日はなぜ嫌われたのか ・在日の犠牲者性は自明か ・レイシズムに至る手法 ・日本人原罪論の系譜 ・改めて「強制連行論」の欺瞞 ・韓国はもはや往年の反共国家ではない ・在日たちよ、日本国籍を取ろう ・韓国人にとってナショナリズムとは何か ・度し難い道徳的優越意識 ・帰化はなぜタブーとされ続けているか ・多文化共生論の誤解 |

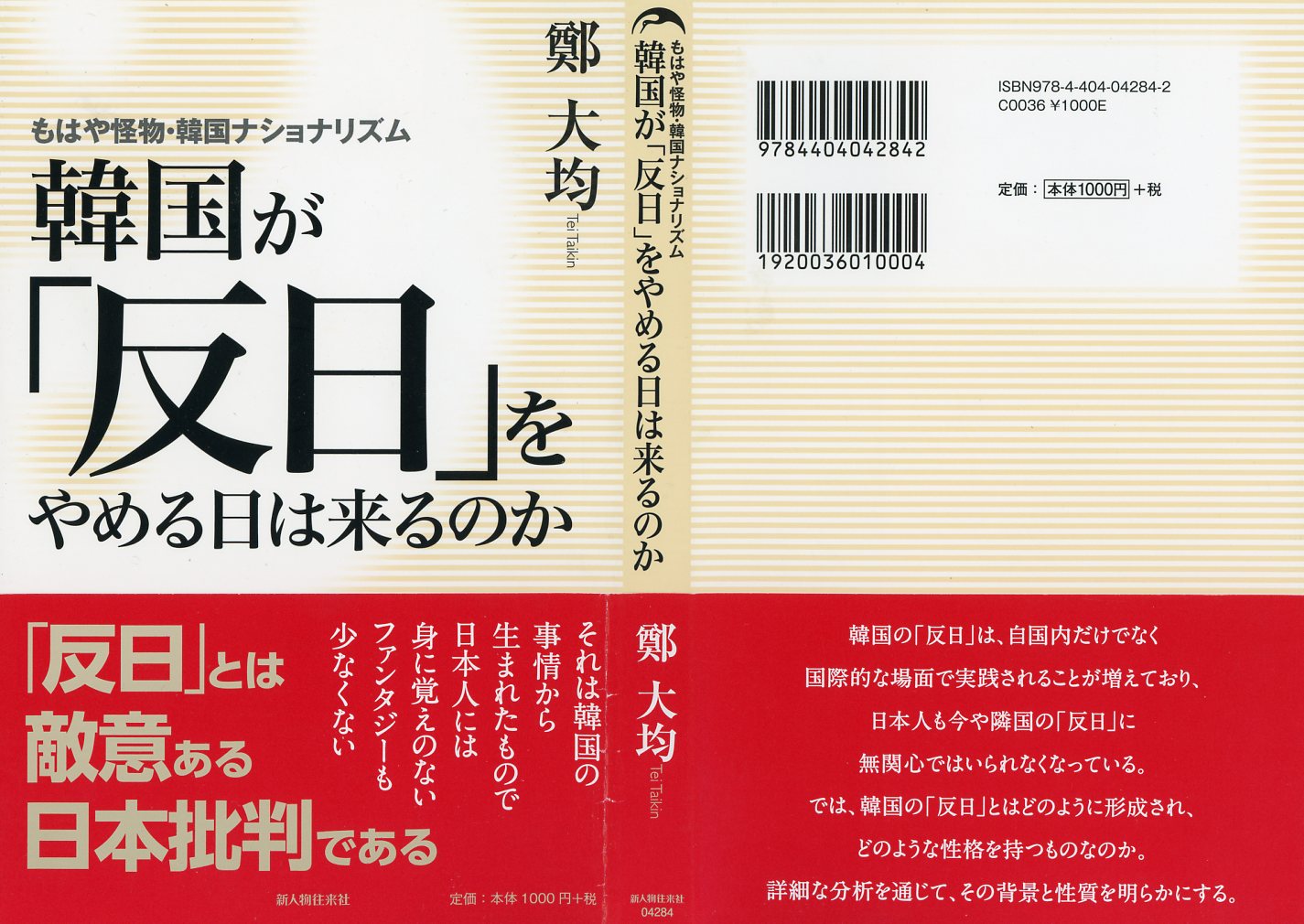

Tei 2012鄭大均 (てい・たいきん Tei Taikin (© Taikin TEI) Forthcoming. 加熱する韓国の「反日」。 彼らの「反日」は韓国の事情から生まれたもので、日本人には身に覚えのないファンタジーから成り立っている場合も少なくない。 とはいえ、韓国の「反日」が、自国の中だけでなく国際社会にも影響力を及ぼすほどに膨張している今、日本側もそれをただ無視したり傍観しているわけにもいかなくなった。 本書では、日韓の膨大な資料や歴史教科書などをもとに、韓国の「反日」のさまざまな性格について類型化し、一口に「反日」といっても、さまざまな様相や姿をとることを詳しく分析していく。 そして「反日」が韓国人のアイデンティティと不可分な関係にある背景を解き明かす。 韓国人が「ナショナリズム」という言葉を聞くとき、日本のそれを連想しても、自国のそれを連想することはできない。 本書は、内省を欠き怪物化した「反日」ナショナリズムが、日本どころか韓国にとってもきわめて危険な存在になっていることに、警鐘を鳴らす一冊である。 |

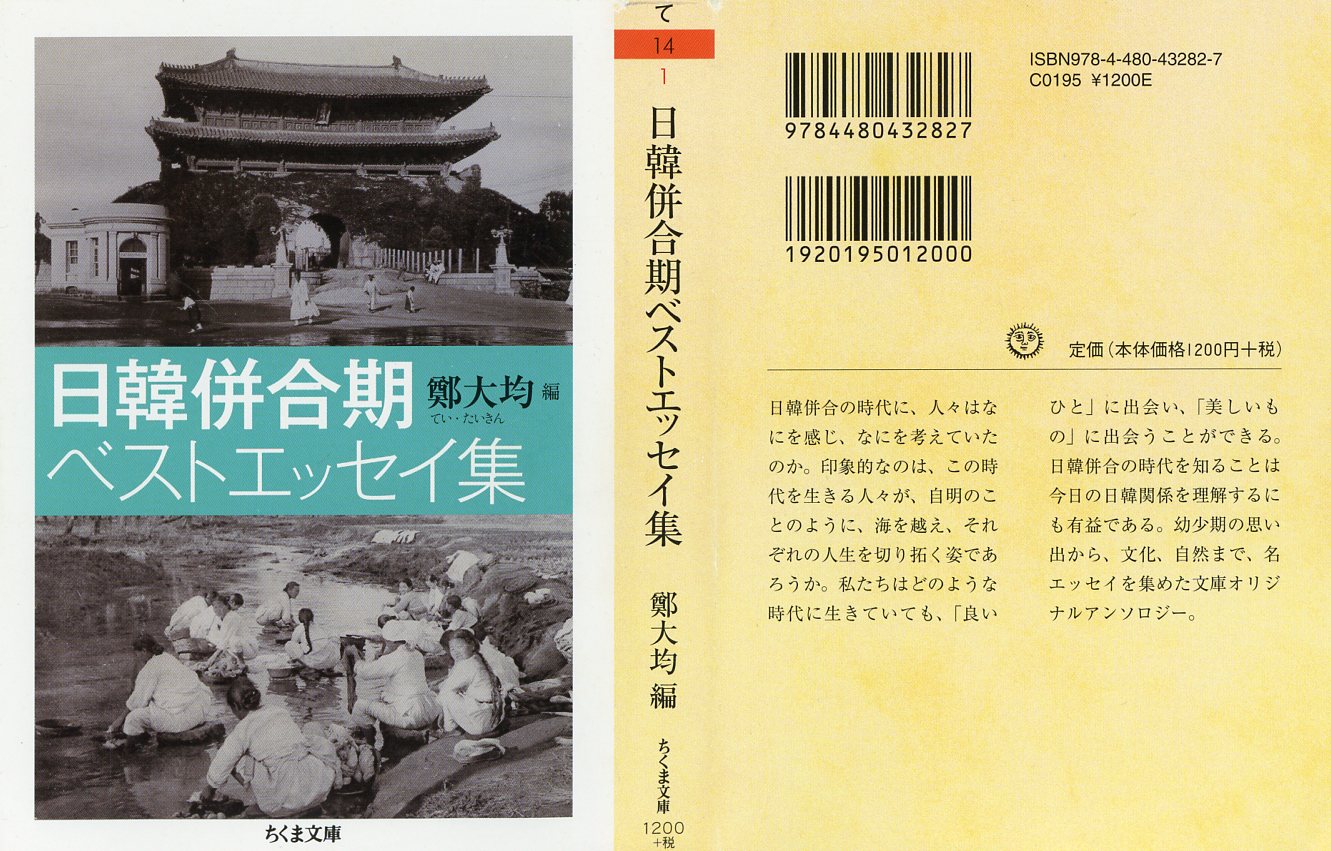

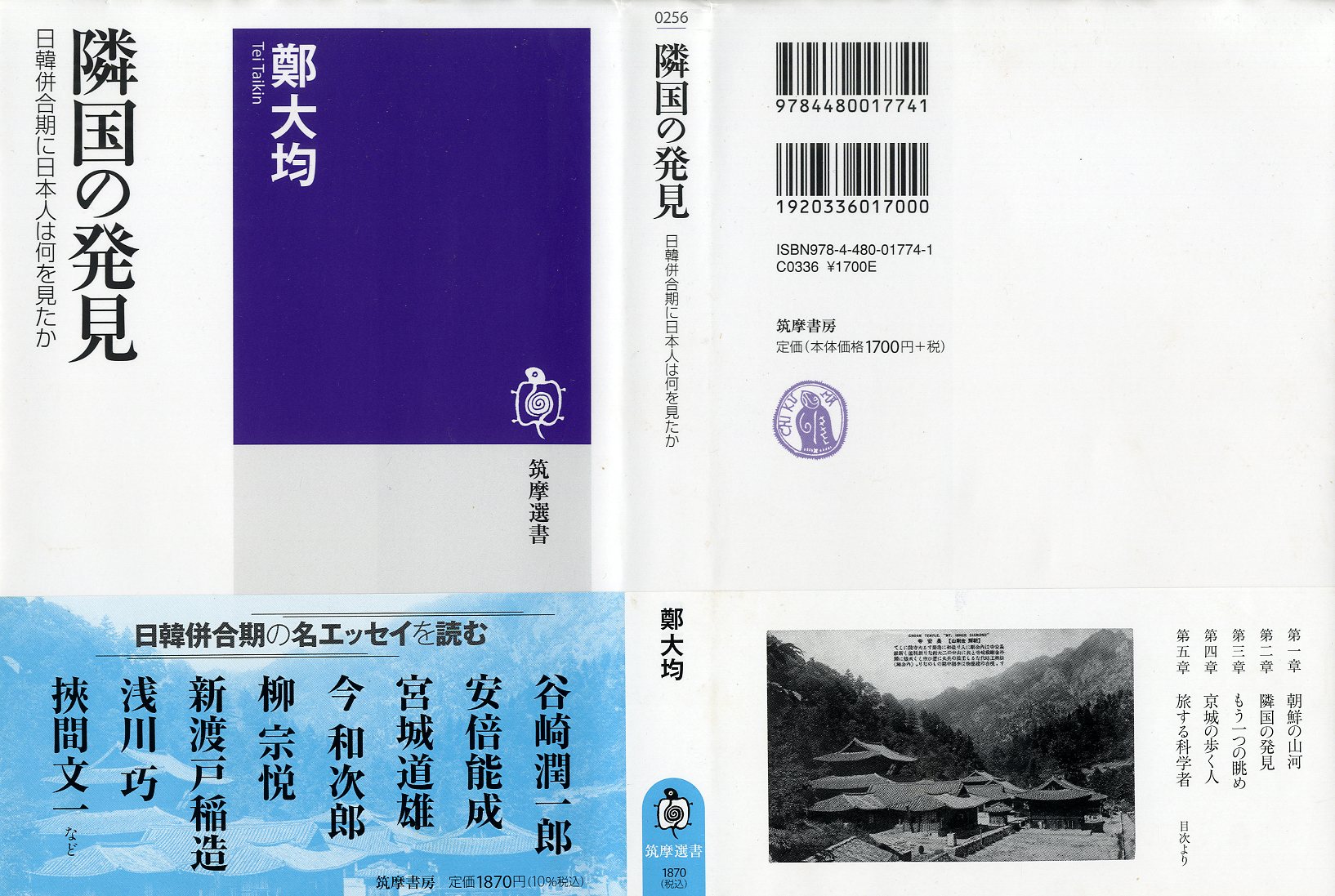

Tei 2015鄭大均 (てい・たいきん) 編 Tei Taikin (© Taikin TEI), editor Forthcoming. 日韓併合期、朝鮮半島で人々は何を感じどう暮らしていたのか。人との交流から朝鮮の自然や文化まで、朝鮮半島での日常を鮮やかに… |

Tei 2015鄭大均 (てい・たいきん Taikin TEI) Forthcoming. |