Keene, Seidensticker et al.

Products of war, commodities of peace

By William Wetherall

First posted 12 November 2010

Last updated 28 March 2023

A version of this article appeared in SWET Newsletter, Number 121, November 2008, pages 12-23.

The addenda include some materials from my notes and stories about my own language teachers.

Article

Introduction

•

In a hundred years

•

If remembered at all

•

Prolific in two languages

•

Memorabilia and momentos

•

The next generation

•

Japanese Language School (JLS)

•

Connecting the dots

Addenda

Keene

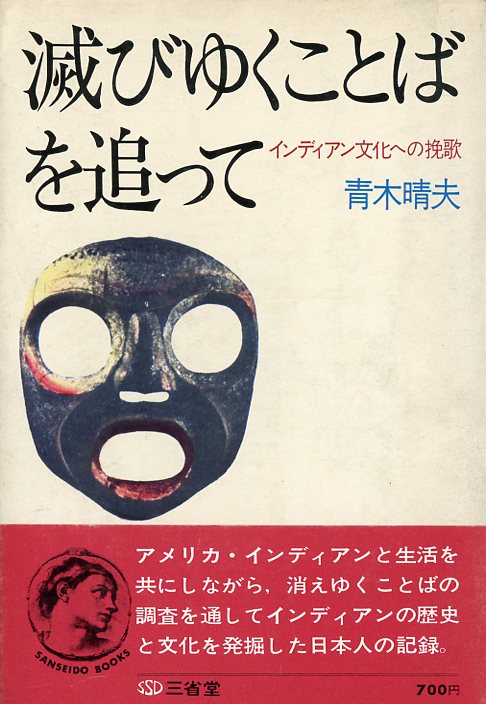

Aoime no Tarojaka

•

Discovery of Europe

Seidensticker

Lithuanian sushi

•

"Snow Country" discussions

et al.

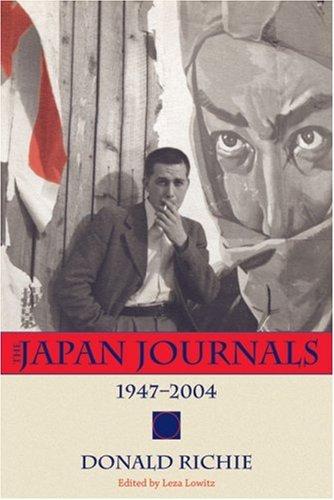

Donald Richie

•

Lynne Riggs

Berkeley teachers

Haruo Aoki

•

Susumu Nakamura (JLS faculty)

•

Elizabeth Carr (JLS faculty)

•

Frank Motofuji (MISLS faculty)

•

Bill and Helen (JLS grad) McCullough

•

Kun Chang

•

Michael Rogers (JLS grad)

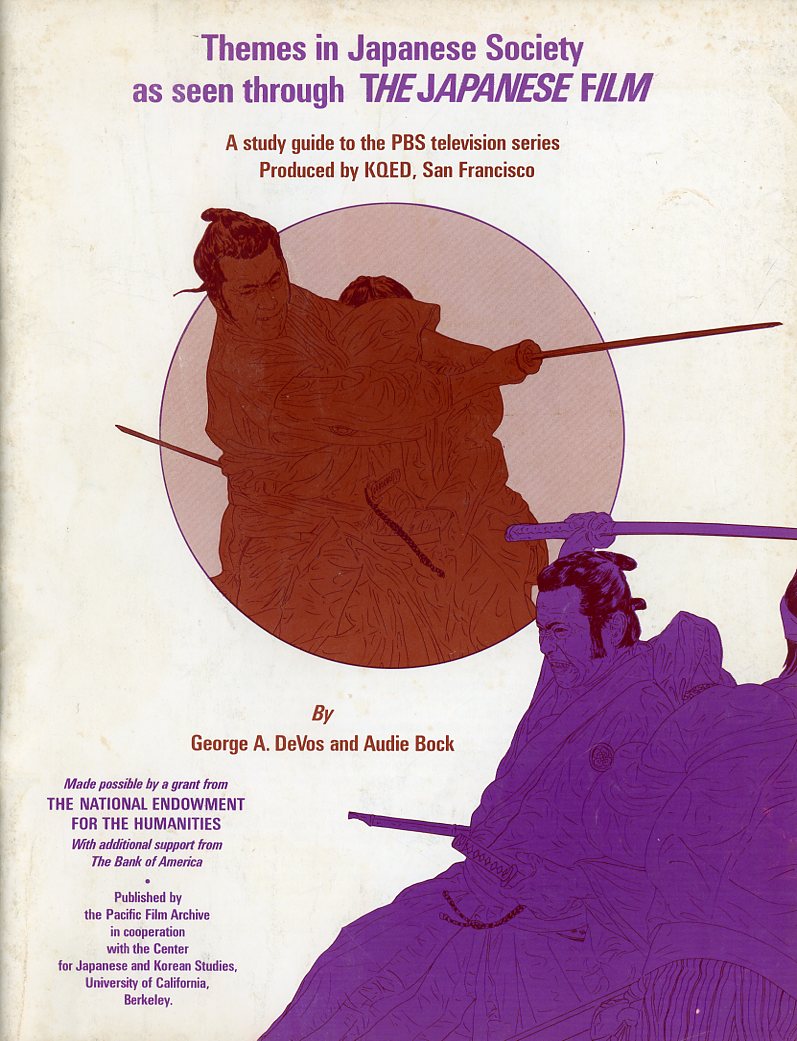

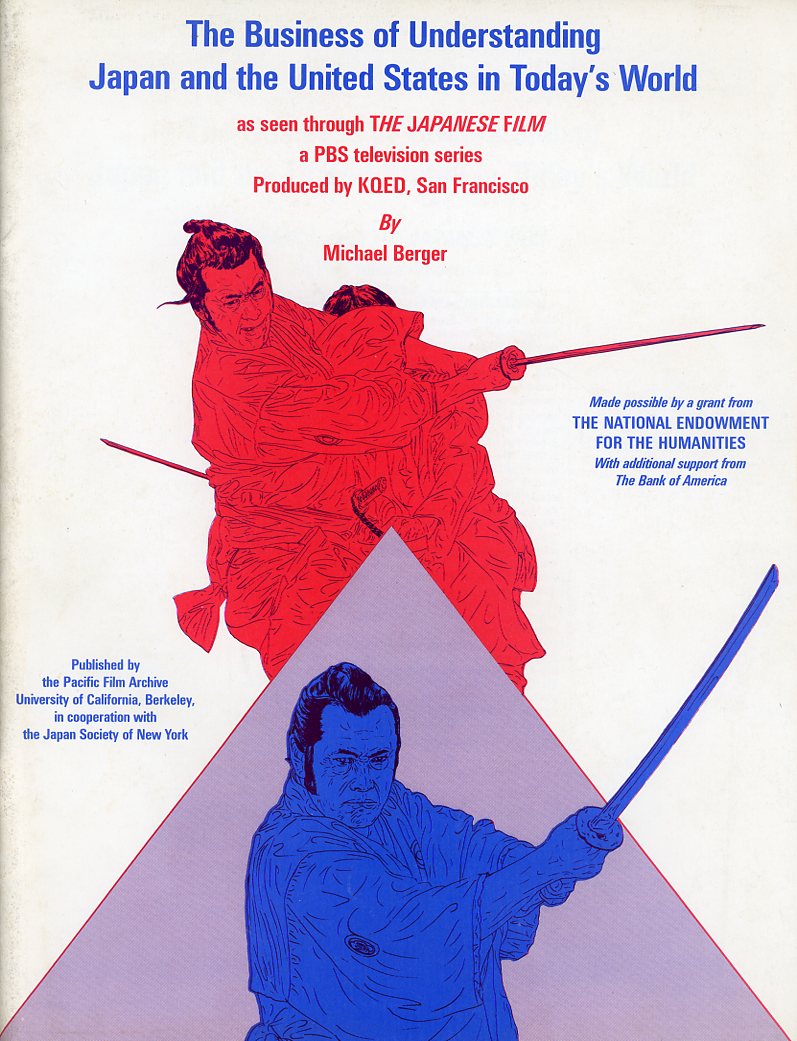

The Japanese Film

The off-camera editoral wars in the production of the study guide for KQED's 1975 PBS television series featuring Reischauer et al.

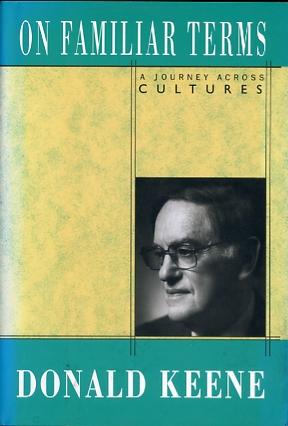

IntroductionFocusing on recently published biographical works by the late Edward G. Seidensticker and Columbia University professor Donald Keene, William Wetherall evokes the personalities and the times of two great promoters of Japanese literature in the postwar era. Intrigued by its title and byline, I recently bought a bilingual book with the mixed-language title Discover Japan: Moshimoshi, sumimasen, dōmo by Donald Keene, E. G. Seidensticker, et al. The "et al." includes forty other writers, translators, and scholars, most now aging but still living in Japan. Published in 1983 by Kodansha International, the book features fifty-four short articles in English with Japanese versions translated by Matsumoto Michihiro, whose name is billed larger than those of the two featured authors. The pieces were selected from the two hundred articles in Discover Japan: Words, Customs and Concepts -- Kodansha's re-issue of the volumes originally known as A Hundred Things Japanese and A Hundred More Things Japanese, published in the mid-1970s by the Japan Culture Institute, one of several organizations -- like the International Society for Educational Information and Kodansha International -- founded after World War II to improve Japan's image in the world. Only the bilingual edition had a byline. But why mention only Keene and Seidensticker -- who had only one article each -- when some among the "et al." had as many as five? Seidensticker might say, with a shrug and a grin, "We were more famous than Richie or Riggs." And the name order? With a sigh and a smile: "Well, K comes before S in both English and Japanese." And if Reischauer had written something? He might grimace, laugh and say, "It would have been 'Reischauer, et al.'" The drama of how Donald Keene (b1922) [d2019] and Edward G. Seidensticker (1921-2007) became rival commodities, especially in Japan, emerges from a reading of their several autobiographical works. As preeminent "buffers" in the postwar realm of Japanese literature with a penchant for column writing, the two men made a classic good-cop, bad-cop team in their journalistic interrogations of life in Japan. Over the decades, Keene's feelings about being asked if he can really read Japanese have softened from annoyance to disappointment. Seidensticker's reactions to being asked if he liked "Japanese sushi" mellowed from sarcastic mischief to mirthful cynicism. Keene, ever humble about his efforts, is a better cop than he thinks, and Seidensticker was never as bad as he tried to be. Keene has been more insistent that Japan is his country as much, if not more, than the United States, and that Japanese is not a foreign language for him. Seidensticker loved Japan no less but found more to complain about in the human condition generally. He had fewer inhibitions about baring his neuroses and exhibiting his fetishes. Keene, more selective and sparing, in On Familiar Terms, declares simply, "I am not making a confession" (page 283). |

|||||

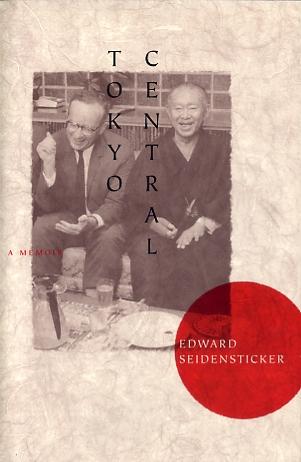

In a hundred yearsEdward Seidensticker knew where he stood in the pecking order of aliens honored by Japan for their service as volunteer or conscript "shock absorbers" between Japan and the outside world -- buffers or ambassadors of mutual understanding, promoters of international goodwill and friendship. In Tokyo Central (University of Washington Press, 2002), he puts it plainly: In 1975 I received the Order of the Rising Sun. It was only a Third Class decoration. Donald Keene had received the same Third Class decoration some time earlier. His was later raised to Second Class. First Class is reserved for people like Reischauer. I have never been raised from Third Class. (pages 228-229) Seidensticker was dogged by Keene's greater fame and popularity in Japan. He wrote Tokyo Central while consulting and citing Keene's On Familiar Terms. But Keene appears not to have returned the favor in Chronicles of My Life (Columbia University Press, 2008). The different sensitivities of the two translator-scholars are clear from their autobiographies. In On Familiar Terms Keene gives several pages to his friendship with Yoshida Ken'ichi (1912-1977), who is standing or sitting next to him in two photographs. In Tokyo Central, Seidensticker introduces Yoshida as the literary critic son of Prime Minister Yoshida Shigeru, then dismisses him as "a friend who turned out not to be" and explains why (pages 148-149). "One evening, for no reason that I could detect, he said substantially this: 'There is a kind of American who is the most urbane, witty, and generally charming person in the world; but you are not it.'" Anticipating Yoshida's response, yet curious to see if he would get an "honest answer," Seidensticker says he asked who the American might be, but all he got was a "tense, high-pitched laugh." Before his achievement of publishing the first complete English translation of The Tale of Genji, Seidensticker worried about both the extent and longevity of his fame. (Diary entry for Monday, 31 May 1971; Genji Days, Kodansha International, 1977, page 59) A gentleman from the Liberal Democratic Party with whom I had a conversation in the Suehiro knew the names of certain of my colleagues, but did not recognize mine when I informed him of it. It is not fun to have what small store of note one has accumulated dissipate itself so quickly. But I suppose it is some comfort to think that in a hundred years most of us will be forgotten. "It is a terrible thing, to seek to be remembered a hundred years," Mr. Kawabata once remarked. In a thousand years not a half dozen people now alive will be remembered. Assuming, of course that there is anyone to remember. Or is it a comfort? |

If remembered at allLike Keene and many others, Seidensticker had trained as a language officer in preparation for service in the Pacific during World War II. After the war, in 1947, he completed a master's degree in politics at Columbia. After passing the Foreign Service exam, he spent some time at Yale and Harvard, grooming himself for a State Department assignment as a language officer in Tokyo, where he worked in the Economic Section of GHQ/SCAP and then in the consulate until 1950. Seidensticker learned that Edwin O. Reischauer (1910-1990), who had been one of his professors, "had not given 'the Department' a glowing report on my year at Harvard" (Tokyo Central, page 44). Decades later he observed of Reischauer: "I liked him, but was by no means sure that I liked his performance as ambassador . . . [and] could not honestly share his views about Japan" (page 177). He remarks how Reischauer was "sanctified by the Japanese" and his house in Boston "turned into a shrine to which busloads of Japanese pilgrims are taken" (page 177). A four-page critique of Reischauer's ambassadorship (1961-1966) is interspersed with comments recorded in his diary entries at the time from friends at the U.S. embassy in Tokyo. For his part, Keene first met Reischauer thinking he might not like him. But in On Familiar Terms he writes, "I could not have been more mistaken" (page 92). When Reischauer died, Keene realized they had embraced similar ideals and that he had unwittingly imitated the late ambassador. In a collection of articles he wrote in Japanese, he called Reischauer his "ikikata no moderu" [model in life] (Nihongo no bi [The Beauty of the Japanese Language], Chūō Kōron Sha, 1993, page 105). Keene's praise of Reischauer extended to Reischauer's self-appointed role as a bridge between the United States and Japan. "I gradually came to realize that there was something of the missionary in me too, and if my work is remembered at all it will probably be because of the books addressed to the general public, not my attempts at 'pure' scholarship (On Familiar Terms, page 94). In 1964 Keene embarked on the writing of a new history of Japanese literature, to update, augment, and correct a history by W. G. Aston (1841-1911), which he had used as a student "often with irritation because of its old-fashioned judgments." In On Familiar Terms, commenting on the "lukewarm or worse" reception to the first volume, which appeared in 1976 under the title World Within Walls: Japanese Literature of the Pre-Modern Era (1600-1867), he confesses to having doubts about it, "and, indeed, all of my writings" (pages 269-272). By 1991 he had published the other volumes in the series, but in the meantime, a new generation of specialists in Japanese literature had emerged, subjecting his work to its own standards of literary criticism. Commenting on the newer approaches to literature studies, he says, "When I read contemporary criticism, much of it phrased in language that I do not understand, I fear that I may have fallen hopelessly behind the times" (On Familiar Terms, page 272). This sentiment is shared by many of Keene's generational peers who "appreciated" the literature that some of the "next generation" preferred to "deconstruct." The battle between the philologists and the postmodernists is still raging. |

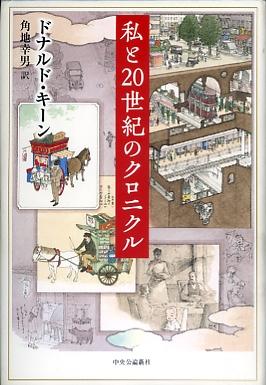

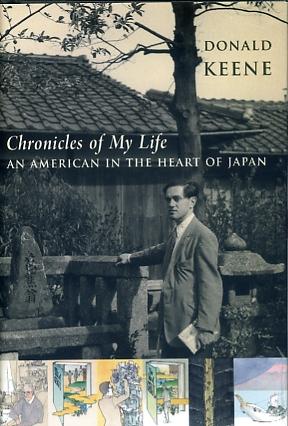

Prolific in two languagesScholars and writers are generally aware that the shelf lives of their books may be shorter than their own expiration dates. Neither Keene nor Seidensticker seems to have entertained delusions about leaving a definitive work. Yet both wrote reams of manuscript, as though to ensure that at least one publication would survive them. In addition to their numerous translations, histories, biographies, and linguistic aids, they authored about three dozen books of more personal commentary -- most published only in Japanese, three in five of them by Keene -- compiled mainly from the hundreds of articles they cranked out for newspapers and magazines in Japan during their annual sojourns in Tokyo, where both owned homes. Most of their Japanese works are "translations" first published in Japan. Many of the English editions are afterthoughts for other markets. Keene's Chronicles of My Life appeared first in Japanese as Watakushi to nijū-seiki no kuronikuru [Chronicles of Me and the Twentieth Century] (Chūō Kōron Sha, 2007). Both books contain the same articles Keene wrote in English for translation and publication in the Saturday morning edition of the Yomiuri Shimbun from 14 January to 23 December 2006, and for simultaneous publication in the Daily Yomiuri. I list the Yomiuri Shimbun first because I get the impression the column was intended to entice the paper's 10-million subscribers to also take the 40,000-circulation English edition, known for its bilingual features. The articles were translated by Kakuchi Yukio (b1948), Keene's principal translator for the past two decades. On Familiar Terms has not been translated into Japanese, as many of the articles on which it was based had already been collected in Japanese publications. The most similar book is Kono hitosuji tsunagarite [Bound to This One Course] (Asahi Shimbun Sha, 1993), the title of which is from a Bashō poem that also appears in On Familiar Terms (page 79). The Japanese book is a collection of articles that had run in the Sunday edition of the Asahi Evening News from 7 January 1990 to 9 February 1992. They had been translated into Japanese by Kanaseki Hisao (1918-1996), a longtime friend and colleague who became one of Keene's main translators. In On Familiar Terms Keene says, regarding another newspaper series: "I was enormously helped by the translator, Kanaseki Hisao, whom I had known for thirty years and who had once taught my courses at Columbia while I was on sabbatical leave" (page 276). In Chronicles of My Life he says only: "Although I wrote my manuscript in English, it was well translated by my friend Kanaseki Hisao" (page 152). This simplification of style and loss of detail invites my characterization of Chronicles (196 pages) as a somewhat updated but very diluted version of Terms (292 pages) -- the result, I suspect, of Keene having to squeeze more of his life into fewer words in a fixed number of write-to-space installments, while keeping in mind the Yomiuri's bilingual reader market. Seidensticker handed his draft of Tokyo Central to Tetsuo Anzai (1933-2008), his principal translator, in 2000. The Japanese edition, poetically titled Nagareyuku hibi: Saidensutekkaa jiden [Passing Days: Seidensticker Autobiography], was published four years later (Jiji Tsūshin Sha, 2004). Anzai, a Shakespeare specialist, writes in his postscript that the Japanese version was supposed to have come out first, but illness delayed his work (page 417). |

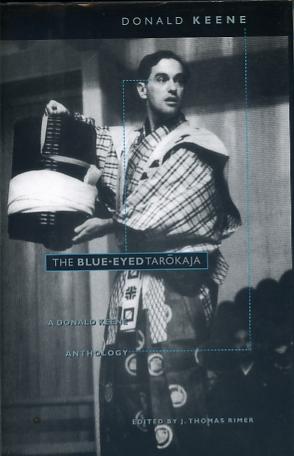

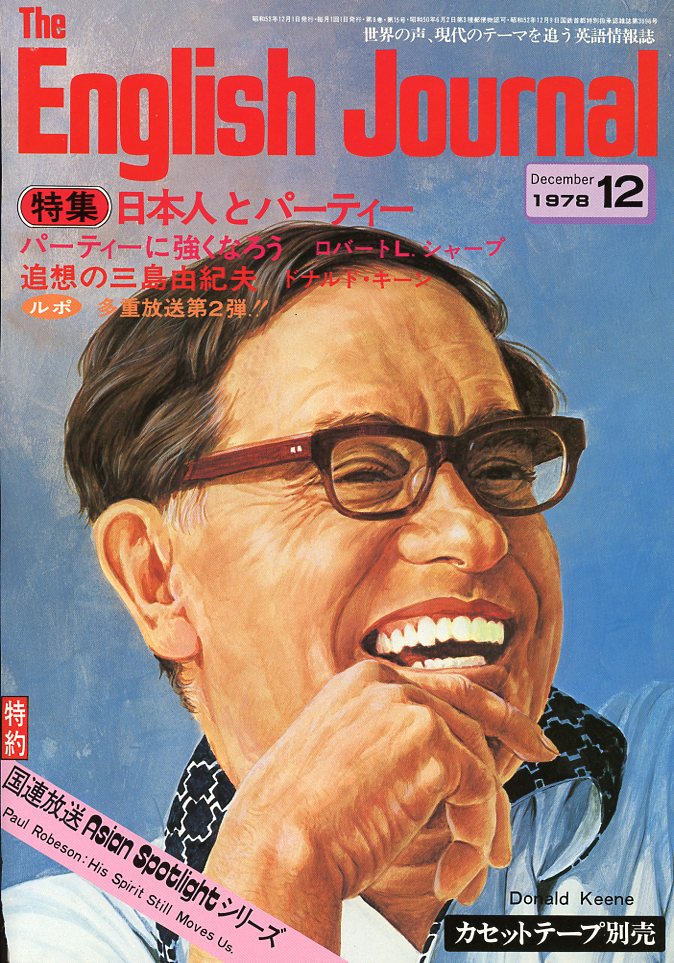

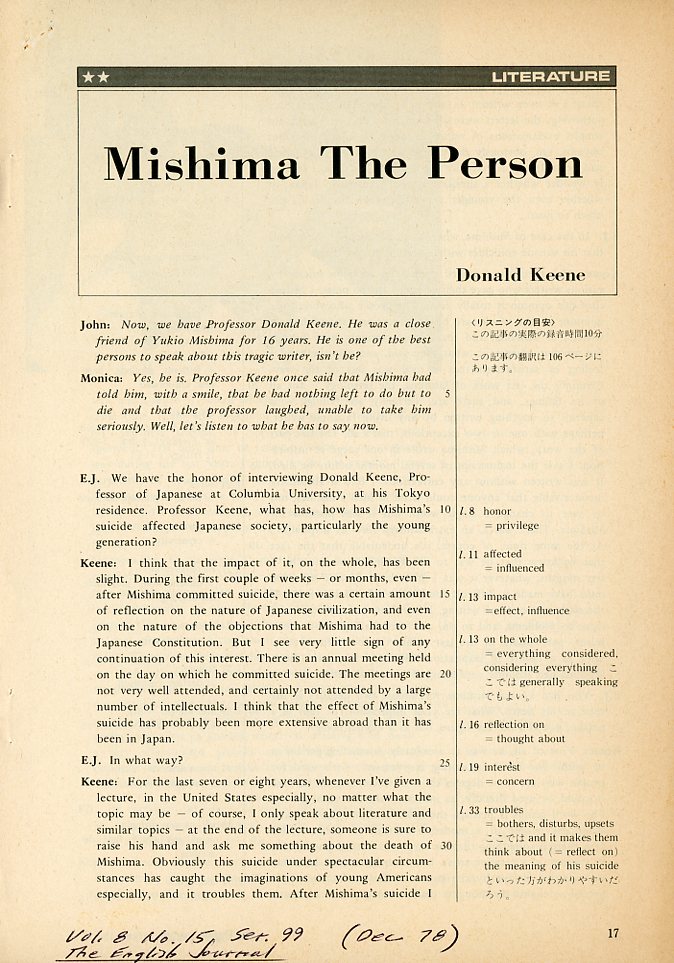

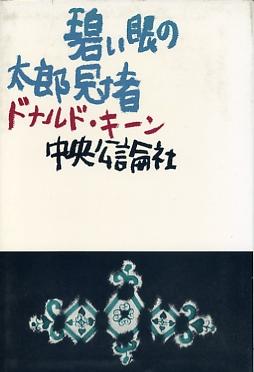

Memorabilia and momentosDisciples and friends of Keene and Seidensticker have also been treading their publishing mills. J. Thomas Rimer, who had studied under Keene, gathered an impressive variety of his mentor's memorabilia in The Blue-Eyed Tarōkaja: A Donald Keene Anthology (Columbia University Press, 1996) -- which borrowed its title from, but is otherwise unrelated to, Keene's biographical Aoi me no Tarōkaja [Blue-eyed Tarōkaja] (Chūō Kōron Sha, 1957). A bilingual spin-off called Mō hitotsu no bokoku, Nihon e [To Japan, Another Motherland] in Japanese and Living in Two Countries in English (Kodansha International, 1999), recycles from the Rimer book the articles Keene had written in English for translation in the Japanese edition of Reader's Digest in the mid-1980s. Rimer calls Aoi me no Tarōkaja the first book Keene published in Japan (page viii), apparently believing Keene (On Familiar Terms, page 181). In fact, it was Keene's second, following by several months the Japanese translation of the first edition of one of his finest books, The Japanese Discovery of Europe: Honda Toshiaki and Other Discoverers, 1720-1798 (U.K. edition 1952, U.S. edition 1954, Japanese edition 1957). If I had to throw away all but two books by Keene, I would keep Rimer's and the revised and expanded edition of The Japanese Discovery of Europe, first published in Japan in a totally new Japanese translation by Chūō Kōron Sha in 1968 -- a year before Stanford University Press brought out the newer English edition. The year after Seidensticker's death in July 2007, the Yushima woodcut artist Yamaguchi Tetsumi, who called his friend and neighbor "Saiden-san," published Yanaka, hana to bochi [Yanaka, flowers and graves] (Misuzu Shobō, 2008) under Seidensticker's byline. In his postscript, Yamaguchi describes the book as a collection of articles Seidensticker had written, some in Japanese, for Ueno, a local magazine (page 202). In his blog, Yamaguchi affectionately remarks that his friend "was quite a trouble maker since his youth" and often quarreled with publishers. Yamaguchi's devotion to Seidensticker was clearly shown when he brought the writer's ashes from Tokyo to Honolulu (Yamaguchi's "tyama-117" blog, 2008-06-12). |

"The next generation"If Seidensticker cultivated the image of an outlaw, Keene went out of his way to appear to be a good guy. Still hearing, it seems, the accusing tones of an unidentified voice, he enters this plea (On Familiar Terms, pages 283-284). "I do not think I have ever 'sold out' to the Japanese in hopes of a reward or even merely of being liked; if I have made mistakes they were what my temperament dictated, not what I thought would bring me advantage." Elsewhere he wears the hat of a fundraiser: "I hope that the Japanese government, recognizing that Japan has no better friends abroad than the Japanologists, will enable young people to create a fourth, a fifth, and many subsequent generations. (The Blue-Eyed Tarōkaja, page 81) The academic and publishing worlds in which Keene has pursued his "missionary" goals are very political, and no one survives without bartering interests. From the very start of his engagement with Japan, Keene -- more like Reischauer than Seidensticker in getting along, being accepted, and cultivating followers -- has clearly leveraged his fame and popularity to bring advantage to himself and his causes. Thanks to Keene's diplomatic skills, learned while growing up and polished during his earliest sojourns in Japan, Columbia University has become the largest hub for Japanese literature studies outside Japan. The Donald Keene Center of Japanese Culture was established there in 1986. It is supported by endowments from several institutions with interests in promoting Japan -- including Shinchosha Publishing, which provides fellowships and sponsors a professorship. Judging from the Keene Center's website, the center's supporters are rather adept at scratching each other's backs. Yet it is fitting that the Shincho Japanese literature chair created for Keene is now held by Haruo Shirane. Shortly after birth in Tokyo in 1950, Shirane accompanied his physicist father and pianist mother to the United States, where they eventually naturalized. Raised in English, he went to England to study English literature, but discovered Japanese literature in translation, and went on to get a doctorate at Columbia. A protege of both Seidensticker and Keene, Shirane is the chief editor of Traditional Japanese Literature: An Anthology, Beginnings to 1600 (University of Columbia Press, 2006) and Early Modern Japanese Literature: An Anthology, 1600-1900 (University of Columbia, 2002). These thick compendia have essentially replaced Keene's epochal compilations, now half a century old -- Anthology of Japanese Literature: from the Earliest Era to the Mid-nineteenth Century (Grove Press, 1955) and Modern Japanese Literature (Grove Press, 1956). In the caption to a photograph in Tokyo Central, Seidensticker describes Shirane as "one of my most gifted students" (facing page 59). Keene and Shirane were featured speakers at a February 2008 event held at Columbia University called "Edward Seidensticker (1918-2007): A Celebration of Lifetime Achievement in Japanese Literary Studies." |

Japanese Language SchoolEven before the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905, Japanese had become a strategic language for the United States. By the end of the nineteenth century, the U.S. had purchased Alaska, annexed the Hawaiian islands, and also nationalized the Philippine Islands. Shortly after Japan's victory over Russia, the U.S. government set up a three-year language training program in Tokyo for foreign service officers and U.S. Navy personnel, out of which came the Hyojun Nihongo Tokuhon (The Standard Japanese Readers) by Naoe Naganuma, who had became the school's chief instructor. The school was pulled out of Tokyo in 1940 as diplomatic relations grew tense. After trial relocations at Harvard University and the University of California at Berkeley, Berkeley became its new home. In June 1942, however, the school, called the U.S. Navy Japanese Language School (JLS), moved to the University of Colorado in Boulder, as most of its instructors had been declared "enemy aliens" and, had they stayed, would have been interned in relocation centers outside the West Coast military zone. Keene gives six pages in On Familiar Terms to his experiences at JLS at Berkeley, where his class matriculated (pages 14-19). He makes no mention of the fact that his class moved with the school to Boulder and graduated there. At the time of the move, Seidensticker was working at the library of the University of Colorado, his alma mater. He would never have studied Japanese had JLS not moved to Boulder. In Tokyo Central he expresses "astonishment" that Keene failed to mention "this event of such major importance to me [which] seems to have meant nothing at all to him" -- and that "neither Boulder nor Colorado is in the index" (page 19). Keene, as though he had never read Tokyo Central, retells in Chronicles of My Life essentially the same story he told in On Familiar Terms -- again with nary a word about Boulder or Colorado (pages 31-35). Yet Keene could not have forgotten the move to Boulder. The Interpreter -- the newsletter of The Japanese Language School Project at the Archives, University of Colorado at Boulder Libraries -- carries a letter from "Donald Keene (JLS 1943)" that begins: "I am sending you some of my official papers as a naval officer. They are extremely boring, but perhaps they may be of use if anyone is interested in tracking where language officers went" (No. 68, 1 October 2003). An earlier issue reported that Seidensticker had begun depositing his papers in the library archives (No. 21, 1 May 2001). |

Connecting the dotsTruth is not something one expects of an autobiography. Honesty is enough. And both Keene and Seidensticker are scrupulously honest in their quests to make entertaining sense of their lives as they age, alone, in their different public and private worlds. Autobiographies open journals and scrapbooks, drop names of friends and foes and famous others, disarm critics, set records straight, wax nostalgic and ideological, crack some private doors, conceal others. All of Keene's and Seidensticker's more personal commentary do one, some, or all of the above. But plunging into their books about themselves and Japan is to enter a bilingual hall of mirrors, some warped or broken, others attached to windcocks. A few stories change from one book or edition to the next, and a version in one language may be rephrased or censored in the other. And neither writer is an exception to the rule that authors should not be taken at their word, especially when reflecting on their own lives. Keene grinds fewer old axes and is less gossipy, but depends on a faulty memory unaided by a diary. Seidensticker, consulting his diaries, thrives on repeating what he recorded others had told him, and is more anxious to settle old accounts. Although both wrote compulsively, Seidensticker's stories have more narrative bite than Keene's, more vicarious thrills per pound of pulp through tabloidesque expose of the "nastiness" (Tokyo Central, page 185) he witnessed behind the polite facade of life and academia. Someone who never met these remarkable men might want to read their personal commentary in order to understand the ordinary human flaws of two individuals who seem, by their many contributions to the postwar development of Japanese literature in English, to be superhuman. For the present generation, their autobiographies are a bridge to a period when there were no laptops or cell phones, no on-line linguistic and bibliographic aids, no half-day trans-Pacific flights, and no college courses on manga. Anyone who has learned Japanese in a classroom, at least in North America, or has studied anything about Japan in English anywhere, stands on the shoulders of luminaries like Keene and Seidensticker -- or others who graduated from JLS or other such schools, or who benefited from government-sponsored programs established in the name of national defense or international relations -- or on the shoulders of their children or grandchildren. Missionary roots also tangle with the lines that connect the historical dots of conflict and commerce between nations. Those of lesser stature who have crossed fleeting paths with such giants live in the shadows of their reflected glory, and sneak bits of their own stories into the legends. |

|

Addenda to "Keene, Seidensticker, et al." and comments on former JLS teachers at UC Berkeley |

Edward Seidensticker (1921-2007)I met Edward Seidensticker a number of times at dinners hosted by a mutual friend, the journalist and photographer Karel van Wolferen, and at Karel's wedding, which Ed attended with Donald Richie. He and Richie lived near each other in the Yanaka area of Taitō ward in Tokyo. Lithuanian sushiDonald Keene's main grievance about his treatment in Japan appears to be the doubts some people harbor about his ability to read Japanese (Chronicles of My Life, Keene 2008, page 178). If I have one complaint about my life in Japan, it is that many people, including some who have read my books, cannot believe that I read Japanese. When I am introduced after a lecture delivered in Japanese, some express apologies for not having a calling card in English or add katakana to help me read their names. A professor at Tokyo University commented about my history of Japanese, "I suppose you read in translation the works you discuss." Keene goes on to admit he has no yearing for miso soup every morning for breakfast, and dreads the thought that he might end up in a retirement home in Japan that serves nothing but (Ibid., pages 179-180). Seisensticker's sense of humor ran a bit differently. When wearing (as he often did) his "Nihonjinron" cap, he liked to poke fun at the English of Japanese who address him in ways he finds peculiar. An essay called "Nihon" (日本) in Ueno (November 1999) explores what he considers excessive self-consciousness about a country that its nationals can't even agree on what to call -- Nihon, Nippon, Japan. Things have to be Japan this, Japan that, as in the way some people speak about things they consider Japanese. He illustrates his point with an experience of how a stewardess addressed him -- in English because, he feels, she was trained to address passengers with "the face of a Westerner" in English, but those with "the face of an Easterner" in Japanese (my translation from Yanaka, hana to bochi, 2008, 86-87). The stewardess (スチュワーデス) asked me in English, "Would you like Japanese sushi?" Hearing this, the somewhat perverse American friend sitting beside me inquired in return deadpan in Japanese, "Nihon no sushi (鮨) wa dame da. Burugaria no sushi wa nai ka?" And the stewardess girl (スチュワーデス嬢) in question replied in the same [unchanged] English, "I am sorry, we have only Japanese sushi." It would seem she didn't realize it was a joke. In an article called "Nihon no tabemono" (日本の食べ物) in Eiyō to ryōri (Joshi Eiyō Tandai, August 1972), he told a similar story (my translation, from translation by Anzai Tetsuo in Yushima no yado ni te, 1976, pages 161-162).

Seidensticker goes on to develop the unoriginal idea that Japanese enjoy believing that Japan is a nation of 100 million masochists who love to hear foreigners say they don't like certain Japanese foods. "Japanese should stop asking foreign guests if they can eat raw fish," he concludes, "and just serve really delicious raw fish." "Snow Country" discussionsEd and I exchanged a couple of letters related to two matters -- a book I loaned him, which he needed to review but lacked a copy -- and his translation of Kawabata's Yukiguni, which I thought was good but could have been better. We also talked about Yukiguni a couple of times on the phone. Ed was predictably himself in his response to my comments that I thought his approach to translation sometimes resulted in English that, while good and even beautiful in its own right, sometimes failed to capture the logic, power, and grace of Kawabata's Japanese. Ed had strong opinions about the translations of others, and about the efforts of others to translate parts of Yukiguni or related works. And on several occasions, he argued in writing against suggestions that he retranslate certain works, such as Kagerō nikki, a late 10th century literary diary he translated as The Gossamer Years: The Diary of a Noblewoman of Heian Japan, first published in 1964. Seidensticker in fact did retranslate a few phrases in Snow Country for a private publication, and gave me a couple of examples of what he himself acknowledged were trivial changes. He felt there was nothing to gain by retranslating the work, and had no intention of giving up his translation rights to accommodate the desire of others who would have liked to have a chance at a new version. Part of Ed's defensiveness is understandable. Readers of English who know the Japanese text will usually agree that, overall, his translation does justice to the story. It was, after all, Snow Country, and Ed's translation of Senbazura as A Thousand Cranes, that resulted in Kawabata receiving the Nobel Prize for Literature. Both translations read better than well enough in English. Why fix narrative features that might depart from Kawabata's style? English is English, and Japanese is Japanese, and there is no reason to attempt to mimic in English the finer elements of Kawabata's Japanese. However, many great works of Japanese literature -- classical and modern -- have been retranslated a number of times. Comparisons show that some translations are better than others. And a number of literary issues are at stake. See, for example, Botchan: Translation rush or glut? and Murakami Haruki's Lost Voice: Translating narrative style. See The light at the end: Kawabata Yasunari's "Yukiguni" for my analysis of Kawabata's translation, compared with partial translations of others, and my owns structural translations of selected parts of not only the final version of Yukiguni but also parts that were cut from early versions. This article includes specifics about my exchanges with Seidensticker and his comments in various articles on his translation. |

et al.At one time or another I have met several of the other contributors to the 100 Things Japanese volumes. The two contributors who would have the most influence on my life as a writer were Donald Richie and Lynne Riggs. ReischauerI never met Reischauer but not because I didn't have any opportunities. I participated in the selection of the 13 films featured in 1974 PBS television series The Japanese Film (see below), produced by KQED in San Francisco, in cooperation with the Pacific Film Archive (PFA). I also participated in and contributed to the writing and editing of an official anthropological guide to Japanese society for the series. Reischauer was the moderator of the series. Keene, Seidensticker, and others in the contemporary who's who of Japanology, appeared as guest commentators. Reischauer was one of the two guests of honor at a dinner, held on 3 January 1975 at the University Art Museum (UAM), celebrating the completion of The Japanese Film. UAM adjoined PFA. The two institutions are now jointly housed and called BAMPFA -- Berkeley Art Museaum & Pacific Film Archive. I received a formal invitation to the dinner but begged off. I was then, and am still, a bit of a recluse, hermit, sociophobe who doesn't like to dress up. Someone who went told me "Reischauer is very short." And yet his shoulders were those of a giant.

|

My language and literature teachers at BerkeleyHere I will talk a bit about all the faculty who were involved in my language and literature education at Berkeley, not all of them language or literature teachers. I had been an Electrical Engineering major in the College of Engineering at UC Berkeley in the early 1960s. After a period of service in the US Army as a medical corpsman and hospital laboratory technician, I returned to Berkeley in 1967 as an Oriental Languages major in the College of Letters and Science. I studied both Japanese and Chinese, then also Korean, but concentrated on Japanese. In my senior year, I petitioned for an individual interdepartmental major in Japanese Studies that allowed me to combine courses in the OL and other departments in a way that allowed me to graduate in 1969. By 1972 I was back at Berkeley in the out-of-the-box Japanese Studies MA program in the Group in Asian Studies. I satisfied the interdepartmental requirements with one foot in Anthropology and the other foot in Oriental Languages. I completed the MA with a written exam in 1973 and continued into a PhD program in Northeast Asian Studies. This was not an off-the-shelf program but one I configured with the help of faculty members who agreed to support my petition to let me pursue such a program and oversee my work. George De Vos (1922-2010) in Anthropology, and Bill McCullough (1928-1997) and Frank Motofuji (1919-2006) in Oriental Languages, were my principle supervisors. Wolfram Eberhard (1909-1989) in Sociology and Delmer Brown (1909-2011) in history joined the committee as outside examiners. Among the committee members, my principle mentors were George De Vos and Bill McCullough (see below). De Vos was especially good at perceiving the complexities of human personality -- how individuals survive in their complex social environments. He worked at the "psychocultural" crossroads of anthropology and psychology and focused on conditions and behaviors that represent problems for individuals and societies -- racial and ethnic minorities, delinquency, suicide, poverty. Wolfram Eberhard, who amassed much of his vast knowledge through years of immersion in life in Asia and other parts of the world, was a Sinologist and anthropologist in the Department of Sociology. I never took a course from him, but his door was open, he loved to tell stories, and he even corresponded with me on the subject of suicide in China and introduced me to others of like interest. Frank Motofuji (see below) was instrumental in developing my interests in translating Japanese fiction. Delmer Brown, while administratively supportive, expected me to be an historian in his mold, which did not appeal to me, and so my contact with him was limited to a single seminar and my oral exams. One of the more influential professors in my life at Berkeley, though I was not one of his students, and in fact never took a course from him, was Chalmers Ashby Johnson 1931-2010), who was both a Japan and China specialist. Chalmers Johnson as he was generally known stayed as a professor in the Department of Political Science from 1962-1992 after obtaining his MA and PhD in the department in 1957 and 1961. Johnson met and married Sheila K. Johnson (b1937) when both were students, she an undergraduate in the Department of Anthropology, and he a freshly minted MA then studying for his doctorate. Sheila, who was born in The Netherlands and migrated to the United States in 1947, went on to get a PhD in anthropology, and an MA in English, both at Berkeley. I did not know Sheila while I was at Berkeley, but became acquainted with her after I had settled in Japan, on occasions when she came to Japan with Chalmers. Chalmers had the image of a "conservative" opinionist while I was a student at Berkeley. I knew other students who had taken a course or two from him, and who were "leftists", and as such they harbored grudges about what they considered his "rightist" views of Japan and China. My impression is that Chalmers became less conservative, and even a bit radical, later in his career, especially after he "retired" from UC Berkeley and took a chair at UC San Diego. From about this point he began to allege that the imperial ambitions of the United States were a threat to the world. The United States maintained more than 700 military bases, several of them in Japan. He concluded that Okinawa was essentially an occupied territory. Sheila, writing a year after his death, began with this remark about his life (Sheila K. Johnson, "The Blowback World of Chalmers Johnson: Remembering the Man and His Work", TomDispatch.com, 10 April 2011). In going through my husband's files, books, and papers after his death, I've been forcibly struck by two things. First, contrary to what many of his obituaries said, his writings and thoughts were remarkably consistent throughout his life. In other words, he was not a right-winger who became more liberal and outspoken as he got older. More than most people suspected, he was a radical all along, whose intellectual impulses were tempered only by his birth in the Depression year of 1931 and his determination to make a decent living without "joining the establishment." Second -- and it was an unavoidable recollection -- he worked with manic energy and maniacally hard all his life. I can testify to his maniacal enthusiasm. No room I was in with Chalmers ever fell silent. His lectures never induced sleep. If no one spoke, he kept talking until he provoked someone to speak. As for Sheila's impression that her late husband was determined not to live without "joining the establishment", Sheila fails to mention that, in the late 1960s and early 1970s, he was a consultant for the CIA. She testifies to a streak of radicalism that apparently Chalmers cloaked for many years. She stops short of claiming that he supported the Free Speech Movement in 1964-1965, or the antiwar and ethnic studies movements mounted by the Third World Liberation Front and other groups from the late 1960s. Her comment is "safe" because "radicalism" is a relative term. Compared to "rightists" he could be called "radical". But I don't believe he ever qualified as a "radical" by Berkeley standards. As a well-informed political scientist and recognized expert on Communist China, he was totally familiar with leftist thought, but ideologically, he himself was nowhere near the left. I would call him a "radical conservative" in the sense that he believed in the truer "conservatism" that eschewed the "radical imperialism" of America's "military-industrial complex". I was not one of Johnson's students, but since he was the chair of the Group in Asian Studies throughout the period that I was getting my MA and PhD under the auspices of the group, I occasionally attended his lectures. He was instrumental in approving my petition for admission to a PhD program in the group, which did not then have an active program. Despite my lack of interest in the field of political science, Johnson did not chase me out of his office when we finished the administrative business at hand. He kindly engaged me in conversation about my studies, and responded to questions I had about his research and other activities. "Professor Johnson" later became "Chal" and, after settling in Japan, I introduced him to Karel van Wolferen, a journalist, writer, and photographer who was then based in Tokyo. I had met Karel through George De Vos at Berkeley, and we had become close friends. Karel and Chalmers knew of each other but had never met. The Johnsons visited Karel during their excursions to Japan, and at times they stayed at his home. Karel's home was a sort of "embassy" and he was its resident ambassador. He hosted many small dinner gatherings for his circle of local friends, mainly journalists and scholars of various fields and nationalities, but also other people who might be in town, such as the Johnsons, or De Vos and his wife Suzanne, who also at times stayed at his home. English was the lingua franca, but other tongues also wagged, including Japanese and Dutch. Karel sometimes broke into Dutch when Ian Burma, Sheila Johnson, or another Dutch or Dutch-speaking friend was there. I interviewed Chalmers in his office at Berkeley for a magazine in Japan, and saw him a few times after he moved to San Diego, at Karel's home in Tokyo. We also exchanged some email concerning his Japan Policy Research Institute, which for a while I supported as a subscriber.

Nakamura's daughterThe following very interesting note from Nakamura's daughter was available as of 15 June 2008 as a Word .doc file -- at a now dead link (http://ucblibraries.colorado.edu/archives/collections/jlsp/53.doc) -- from the Special Collections & Archives of the University Libraries of the University of Colorado at Boulder.

Susumu Winston Nakamura was born in California on 17 March 1908. A 1943 directory for Boulder, Colorado lists "Susumu W Nakamura" with his wife "Fumie A Nakamura" at 751 Grant Place (Ancestry.com). He passed away in Berkeley on 15 June 1989. His mother's maiden name was Watanabe.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Japanese FilmThe off-camera editoral wars

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Have met Audie. Went over introduction and one of the theme sections. She's a fine organizer in terms of development and continuity, but seems inclined toward sterotypes [sic], superlative generalizations, and sometimes imbalance. She also seems ready to take shortcuts in quality under deadline pressure, which may be creating the problems I have noted. But it is my experience, such as it is, that inadvertent slipping into stereotypes and unsupportable generalizations are better attributed to belief in them. She may have taken your general approval of introduction draft, and Sheldon's general approval, both too easily and too seriously. In any case, she has experienced what it feels like to be criticized by Wetherall. I thought she took it gracefully. Audie didn't want to let me retype my corrected copy for her. Said there is no money to pay me for typing. I can see she comes from a mercenary world. She said I shouldn't be so noble to offer to type for nothing. Maybe she's defending her control MSS. That's her prerogative, but I will argue that it gravitates against the objectives of the project to get out the best possible copy. There is not enough time for her to be originator, editor, and typer all in one. She would be doing enough to apply her obvious talents to producing reasonably accurate drafts, and letting me make it readable in terms of writing criteria, i.e., conciseness, clarity, and so forth. |

There were also problems with the editing of advertising copy and subtitles. Misphrasing in promotional copy, and lack of coordination between subtitling and content in the official PBS guide, could result in contraditions in view point. Much of the "quality control" was left to chance. Editorial policy was developed on the fly, and at times didn't really qualify as "policy". The undated memorandum to De Vos included the following remarks about this problem.

|

I still don't see that Sheldon is preparing to route advertising copy through Audie. I get the impression from her, also, that when she was first approached to be editor of the project, that she did not foresee being overall editor in the sense that all materials would be passed through her hands for checks on romanization, accuracy, tone, etc. So I see some basic conflicts in what we were at one time led to believe about quality control. I am told [by Audie] that [Joseph L.] Anderson is indeed resubtitling, and that "someone" is checking him, but if there's no tie-in with those of us who have been most sensitive to subtitle problems, how do we know that he has improved [the titles] in areas we felt needed improvement? And if we write interpretations that depend on these problem areas being improved -- and we discover that Anderson has left some of these areas untouched -- how will this come across to a critical viewer? Again, I would say we need to see typeout of the new subtitle sequence, along side Japanese scenario. Why we can't have these is beyond me. Certainly they exist -- and all it would take is a phone call to the people who have them, and a few dollars Xerox and mailing, and they would be here for our perusal and peace of mind. |

Joseph L. Anderson was the co-author with Donald Richie of the then (and still) standard introduction to Japanese filmdom, The Japanese Film: Art and Industry (Charles E. Tuttle 1959, Evergreen [Grove Press] 1960), an expanded edition of which is still in print. Anderson was the primary researcher. Richie the main writer.

I continued to work with De Vos, Winnie Dahl, and Ruth Heinze. I and Ruth sent a formal letter to Sheldon Renan, dated 7 August 1974, in which we asked that our names not appear in the official PBS study guide. "We are aware that it was Professor George A. DeVos's intention that we be acknowledged. Moreover, we are aware that a brief acknowledgement including our names was drafted and that the draft was submitted with Professor DeVos's and our consent to Audie Bock, in Professor DeVos's and our presence, for inclusion in the study guide. / However, we herein withdraw permission to use our names in any manner whatsoever related to the above-mentioned study guide." Sheldon returned the original copy to me with this note at the bottom: "Bill, OK. Sheldon Renan 8 August 74".

In time we all got along. Ruth and I withdrew our objection to acknowledging our participation in the Themes in Japanese Society study guide. I am credited for my assistance along with Felicia Bock (Audie's mother, see below), and Winifred Dahl and Ruth-Inge Heinze.

I saw Winnie again in Japan, as she was briefly there in the early days of my fieldwork, which began in the summer of 1975. Ruth, who was older than De Vos, was full of energy and wisdom, and I regret not having any further contact with her. And I never again crossed physical paths with Audie or Felicia, though I later met a few people who knew them -- including Donald Richie -- and now and then I encountered Audie's and Felicia's publications (see below).

Japan Society panel discussion

In early January 1975, KQED sent me a 1-inch-thick box containing the entire press kit for The Japanese Film series. The kit consisted of 14 folders -- a generic folder pertaining to the series in general, and a folder for each of the 13 films -- all stuffed with data on the films, synopses, glossy stills, and lots of promotional copy.

The production of The Japanese Film was financed mainly by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. However, part of the costs were underwritten by the Bank of America in San Francisco. BoA hosted a panel discussion in the A.P. Giannini Auditoriam in its downtown tower. Sheldon Renan chose me to be one of the four panelists -- with himself, Michael Berger (a journalist who wrote a "business" oriented pamphlet for the series), and Frank Motofuji. Sheldon also asked me to moderate the panel. In publicity created by The Japan Society of San Francisco, which facilitated the panel, I was billed as "Bill Wetherall".

The panel discussion began from 12 noon on Thursday, 6 March 1975. The idea was to draw a lunch-time audience. As it wasn't a formal dinner party, I wouldn't have to stand around, socialize, and pretend I was having fun. I didn't even have to dress up, but I did -- to a point. I pulled my only sports coat out of the closet -- a light tan, heavy tweed jacket I still have, and have worn perhaps a dozen times in my life, mostly in Japan -- and bought a new baby-blue Oxford-cloth button-down shirt. It was the nearest I ever came to being a westcoast Ivy Leaguer. Michael Berger accused me of trying to pass as a journalist. Whatever I was, I strutted my stuff. It wasn't live, but it had to start and end on time, and given the mix of panel members, I scripted everything except what they would actually say. Everything unfolded like clockwork within the 50-minute time slot. And by all accounts it was well received.

At the panel discussion, I introduced Sheldon as "until this year the director of the Pacific Film Archive". In October 1974, Sheldon had announced his resignation, effective 1 January 1975, in order to become an independent producer. At the time of the panel discussion, he was already busy with the creation of three major TV series for showing on PBS stations nationwide.

Catalog project

In addition to helping De Vos, I authored a 24-page proposal titled "Stanford-Berkeley East Asian Studies Center Pacific Film Archive Japanese Film Collection Catalog Project (8 March 1974). I did this through the Stanford-Berkeley East Asian Studies Center, which was then under the co-direction of Albert Dien, a professor of Chinese at Stanford, and Haruo Aoki, a professor of spoken Japanese and of Japanese linguistics at Cal, with whom I am still in touch (see above).

The proposal provided that students interested in Japanese films be hired to catalog the Japanese films in PFA. Frank Motofuji endorsed this idea as the cheaper and more effective way to catalog the films, and he agreed to supervise the cataloging. Sheldon Renan of course wanted the films -- some of them acquired from Shochiku as recently as June 1973 -- properly cataloged. My files include correspondence from PFA's technical director showing a breakdown of PFA material costs and administrative overhead.

There are several memos to Motofuji and me from Eiji Yutani, the Japanese collection bibliographer at the East Asiatic Library, concerning the acquisition of Japanese film journals and other reference materials. In a memo to me dated 28 February 1974, Yutani estimated that it would cost "$1300-$1500 [to acquire] back numbers of Kinema Jumpō needed at the library -- "[s]ome 1300-1400 numbers in fifty-four volumes, 1919-1972".

In those days, most back issues of Kinema junpō would probably have been available. Today it would be extremely difficult to amass such a collection, and for most libraries the costs would be prohibitive. Some Taishō and early Shōwa issues run from 5,000 to 20,000 yen -- if you can find them.

The catalog project never got off the ground while I was there. Motofuji remained involved and eventually PFA had a proper catalog and not just lists of titles, which was all that existed at the time of the PBS series.

Syllabuses and other classroom guides

George De Vos and Winifred Dahl co-authored Japanese Culture Through the Camera's Eye, an 85-page syllabus for Anthropology X 123, a Univeristy of California Extension (Independent Study) course (1974).

Francis T. Motofuji wrote Japanese Film: Thirteen Postwar Masterpieces, a 123-page syllabus for Oriental Languages X 146, another UC extension course (1974).

In addition to these syllabuses, which were intended for use in UCB's continuing education program, there were several initiatives to develop a guide to the PBS film series for use in secondary classrooms. I myself submitted a 17-page proposal, dated 20 October 1974, to Tony Namkung, at the Stanford-Berkeley Joint NDEA Center. NDEA means "National Defense Education Act" and the center oversaw the language and area studies programs that the Federal U.S. government funded through the act, including NDEA fellowships. of which I was one of several recipients at UCB and Stanford. Tony was a graduate student in history, a teaching assistant for Robert Bellah in sociology, and a close friend I had met in Aoki's elementary Japanese course on the first day of classes in the fall of 1967. Tony, who was raised in Japan, was immediately placed in the immediate Japanese course taught by Susumu Nakamura, where he could focus on reading and writing (see above).

On 3 March 1975, Tony informed a list of concerned individuals -- Harumi Befu, George A. DeVos, Peter Duus, Ronald B. Harring, Francis Motofuji, and William O. Wetherall -- concerning the "Teaching Japan in Schools (TJS)" project at Stanford, which the Joint NDEA Center had partly funded. The first TJS proposal failed and was in the process of revision. I have no idea what became of the effort. By July 1975, I was in Japan, beginning my fieldwork on suicide, and would never again reside in the United States.

Felicia and Audie Bock

Audie's mother, Felicia Bock (1916-2011), was perhaps the most interesting behind-the-scenes character in the PBS film project drama. I have no knowledge of whether she was formally contracted to contribute to the film project, or whether she was merely involved as Audie's mother. I met her only once that I clearly remember, after meeting Audie. And there was no doubt that she was Audie's mother.

I had bought Felicia's translation of the Engishiki (延喜式), an early 10th century compendium of texts related to Shintō rites, which she published in 2 volumes as Engi-Shiki: Procedures of the Engi Era (Tokyo: Sophia University, 1970, 1972), and naturally I was curious about the face that went with the by-line. It's always a pleasure to meet someone who actually finishes and publishes a work.

The back flap of the dust jacket of Volume 1 describes Bock's life like this.

The author, Felicia Gressitt Bock, is Lecturer on Japanese and Chinese cultural histories and Far Eastern Buddhism at the University of California Extension. She sudied Japanese language and history from 1937 to 1941 at Kobe College in Nishinomiya, Japan, and took up Japanese studies at Columbia University. In 1948 she obtained an M.A. in Japanese from the University of California and in 1966 was awarded the Ph. D. in Oriental Languages. She was born in Tokyo and lived in Japan for more than 15 years. She and her husband, Charles Kurt Bock, were married in Tokyo in 1940. They have three children.

The above 2 volumes cover Books I-V and Books VI-X of the 50 books (kan 巻) of Engishiki. In 1985, Bock published two more books in Classical Learning and Taoist Practices in Early Japan, With a Translation of Books XVI and XX of the Engi-Shiki (Arizona State University Center for Asian Studies, Occasional Paper, Number 17, 1985).

One of my hobbies is to trace historical people in records available through genealogical websites like Ancestry.com.

Felicia Ray Gressitt was born in Tokyo and raised in Japan until age 15, when she went to the United States to study at Mount Holyoke in Massacheusetts. After graduating from the college in 1936, she returned to Japan and taught for a while at Kobe College (Kōbe Jogakuin 神戸女学院), a Christian women's college founded in 1873 (now called Kōbe Jogakuin Daigaku 神戸女学院大学 in Japanese).

On 1 November 1940, Felicia Ray Gerssitt, a U.S. citizen, married Kurt Karl Bock, a German national born in Austria in 1910, at the American Consulate in Yokohama, according to a Consular Marriage Certificate. The certificate states that both parties were then residing in Yokohama.

On 10 June 1941, Karl Bock filed a "Declaration of Intention" to naturalize with a New York district court. On 8 October 1942, he filed a "Petition for Naturalization" with the court, on which he declared that he had emigrated from Yokohama to the United States for permanent resident, arriving in Honolulu on 13 January 1940, and had not been absent from the U.S. for a period of more than 6 months since then. The petition states that he and his wife Felica had married on 1 November 1940 in Tokyo [not Yokohama], and that Felica entered the United States for permanent residence on 10 April 1941. A court order dated 13 December 1944 authorizes revisions in the petition, including the change of "Karl" to "Charles". And on this same date, Charles Kurt Bock was issued a Certificate of Naturalization and thereby became a U.S. citizen.

Felicia studied at Columbia while she and Charles were residing in New York. Audie was born in New York but raised in Berkeley while Felicia was studying at Cal. Her mother's attachments to Japan led Audie to her interests in the country.

The back flap of the dust jacket of Japanese Film Directors (1978), the book adapation of Audie's doctoral dissertation, describes her life to that point like this.

Audie Bock was born in New York and grew up in Berkeley, California. After graduating from Wellesley College in 1967 she went to Japan where she taught English at International Christian University in Tokyo. Ms. Bock has been an editor for English-language books in Tokyo and has worked on Japanese cinema projects in both the United States and Japan. She has also taught Japanese cinema at Yale University and at Harvard University where she is enrolled in the Ph.D. program in fine arts. Ms. Bock also edited and coauthored the education material for the 1975 PBS television series "The Japanese Film"; since then she has served as Film Program Coordinator for the Japan Society of New York. In 1976-77, while in Japan on a Fulbright Doctoral Dissertation Research Fellowship, Ms. Bock also wrote film reviews for The Japan times.

Audie became very active in Alameda County and State of California politics. She served one term as a Green Party representative to the California State Assembly, for the municipalities of Oakland, Alameda, and Piedmont, in Alameda County, which includes Berkeley. She ran for a number of other offices, and once even ran for governor.

A long political "infomercial" on UCLA's Digital Library server includes the following remarks (circa 2003).

|

The Honorable Audie Elizabeth Bock (D) . . . Assemblywoman Bock is a lifelong resident of Alameda County, educated through the Berkeley public school system. She holds a Certificate in Non-Profit Management, Executive Director, from the University of San Francisco; an M.A. from Harvard University in East Asian Studies; and a B.A. from Wellesley College in French. She is trilingual in French, Japanese, and English. . . . She was film director Akira Kurosawa's official translator in the United States and translated live for him in 1990 at the 63rd Annual Academy Awards Ceremony as he accepted a Lifelong Achievement Oscar. A motion picture distributor and a writer, Ms. Bock also authored several books, including a translation of Akira Kurosawa's memoirs and a textbook on renowned Japanese filmmakers. . . . |

Yet another on-line source -- www.liquisearch.com, which attributes its information to Wikipedia Career (Creative Commons) -- describes Audie Bock's "Early Life and Career" like this.

|

Bock was born and raised in Berkeley, California. She attended Berkeley High School. She then attended Wellesley College, graduating in 1967. For the next five years, she lived in Japan, near Tokyo, where she taught English and helped to publish English-language travel books. After that, she returned to the United States to attend Harvard University, where she received a master's degree in East Asian studies. She stayed at Harvard to receive a PhD, where she wrote a dissertation on Japanese film directors. This involved returning to Japan and interviewing some directors, including Akira Kurosawa; the two struck up a friendship as a result. Bock's dissertation was published as the 1978 book Japanese film directors . . . . |

In 1985, Japan Society Gallery published Naruse: A Master of the Japanese Cinema, Audie's study of the director Naruse Mikio (成瀬巳喜男 1905-1969). His 1960 "When a Woman Ascends the Stairs" -- a faithful translation of its poetic Japanese title "Onna ga kaidan o noboru toki" (女が階段を上る時) -- was one of the films chosen for the 1975 PBS film series.

The Naruse film was telecast on the evening of Thursday, 6 March 1975, the day I moderated the "Japanese Films: A Cultural Mirror panel discussion in San Francisco, before a lunch-time audience of mostly businessmen and businesswomen. My closing remarks were as follows (based on my own script, the introduction and closing of which I followed very closely).

Thank you very much for giving us your time and attention. In closing, I would like to remind everyone that it is still Thursday, that it is still daylight outside, that you've got plenty of time to get home to watch this evening's film, When a Woman Ascends the Stairs, in which you will see something of the bars and cabarets in which Japanese businessmen and even businesswomen are thought to lubricate their interpersonal relations. Thank you.

Audie's book on Naruse became very hard to get. She mostly single-handedly pioneered English research on Naruse, among a few other directors she studied.