Tojin Okichi monogatari

A tale of "Chink Okichi" and Townsend Harris

By William Wetherall

First posted 23 September 2006

Last updated 18 August 2010

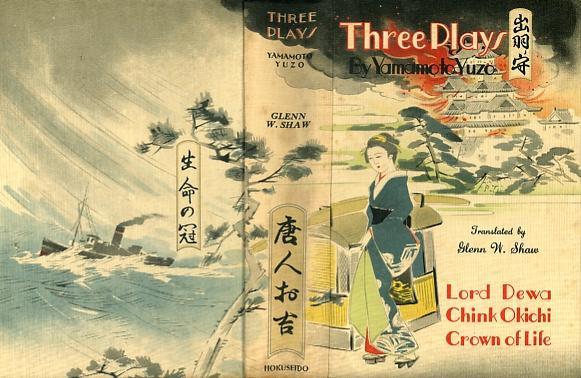

Tojin OkichiThough "Tōjin" (唐人) essentially refers to a "Chinese" or "Chinaman" or "Chink" in Japanese, later in the Tokugawa period (1600-1868), and during the Meiji era (1868-1912), some people used "Tōjin" to mean any foreigner, even those from Europe or the Americas. A good example is the legendary reference to Saitō Kichi (1841-1891), the mistress of the American Consul Townsend Harris (1804-1878), as "Tōjin Okichi". Many translators would render this extended use of "Tōjin" as "foreigner" or "barbarian" rather than "Chinese", and most would utterly balk at "Chink" or even "Chinaman". However, conflating "Tōjin" with other words that do, in fact, mean "foreigner" or "barbarian" robs the word of its metaphorical existence. It makes more literary sense to keep the Japanese metaphor of "Tōjin" in English. For it the metaphor that a listener or reader is supposed to hear or read -- and its meanings are suggested by deeper, less audible or visible elements. There are, in fact, firm sociolinguistic grounds for rendering "Tōjin" as "Chinaman" or even "Chink" in the case of "Tōjin Okichi". Just as "Tōjin" in Japanese came to encompass people unrelated to China and even to Asia, the semantic parameters of "Chinaman" and "Chink" in Enlgish were extended to included people other than Chinese. Glen Shaw's translation of "Tojin Okichi monogatari"In 1929, the novelist and playwright Yamamoto Yuzo (1887-1974) wrote a four-act play called "Nyonin aishi: Tōjin Okichi monogatari" (女人哀詞 / 唐人お吉物語) or "A woman's lament: The story of Chink Okichi". Glenn W. Shaw (1886-1961) translated the Okichi play, with two others by Yamamoto, in a collection entitled Three Plays (Tokyo: The Hokuseido Press, 1935). Shaw's long title for the Okichi play is "The Story of Chink Okichi", and the short title is simply "Chink Okichi".

Shaw wrote haiku as 尚紅連 -- which, in the kana orthography of Shaw's day, would have been romanized "Shau Guren" -- though a Chinese-speaking friend of mine playfully reads it "Shang Hong Lian" and thinks it sounds like the name of a buddhist priest. A serious student of literature and one of the better translators of his generation, Shaw did not render "Tōjin" as "Chink" in order to be provocative, but to capture the spirit of the word -- which was not subject to present-day aversions. Shaw on "Chink"This is what Shaw himself says about his choice to translate "Tōjin" as "Chink" (Yamamoto 1935: vi-vii, underscoring mine).

In the drama, however, "Tōjin" is not just used by people disparage Okichi. She herself -- both before and after she submits to pressure to attend to the American consul's needs -- derogatorily refers to him and his kind as "Tōjin" and even, in Shaw's phrasing, "blue-eyed Chinks" (Yamamoto 1935: 108). Generally, however, "Tōjin" (唐人) would refer Chinese, while hairier Euroamericans would be called "Ketōjin" (毛唐人) or just "Ketō" (毛唐), meaning "hairy Chinese" or "hairy Chinks". Tojin and ChinkThe meanings of both "Tōjin" and "Chink" are found beneath their surfaces. Even the syntactic ambiguity of "Tōjin" used attributively with "Okichi" is precisely mirrored in Shaw's direct translation: in either language, someone who does already know the story would have to read or watch the play in order to learn whether Okichi herself is a "Tōjin / Chink" or what. Both "Tōjin" and "Chink" are essentially descriptive labels, and whether they are used to disparage Okichi, or anyone, is a question that has to be left to the reader -- much as readers are left to iron out the emotional wrinkles of "leper" in John Farrow's classic Damien the Leper (New York: Sheed & Ward, 1937), among many other novels that feature "lepers" -- and not "people affected by Hansen's Disease" as a United Nations human rights report might have it. "Tojin" in Japanese"Tōjin" has in fact been used in Japanese to disparage someone. An early example is found in Odokebanashi ukiyoburo [Funny stories: Floating world bathhouse] (1809-1813), by Shikitei Sanba (1776-1822), an Edo gesaku writer and humorist whose real name was Kikuchi Hisanori. Ukiyoburo relates talk among bathers at a public bath, where townspeople congregate and gossip. In one passage, a man cusses someone saying "Edokko mo susamashii, kono Tōjin me" [Edoites are awful, you damned Chinamen] -- meaning Edo people don't understand the ways of things. [Note]

"Chink" in EnglishJust as "Tōjin" in Japanese came to be used by some people to refer to people were were not "Chinese", the term "Chink" in English has a long history of use in related to Japan and Japanese. One example is Mable and Helen Hyde's Jingles From Japan as Set Forth by the Chinks (Tokyo: Methodist Publishing House, 1907), a book for children. There are numerous parallel examples. "Amerika" and "Amerikajin" in Japanese, and "Meiguoren" in Chinese ("Bikoklang" in Taiwanese), have long been used as purely racial labels, especially for Caucasians and others of unknown nationality.

|